Translator’s note: the word “disenclavement” (and its derivatives) here refers to the act of taking a region out of isolation, in this case by building a motorway link. In French, a region is said to be “enclaved” (enclavée) when it is poorly served by transport and its access is difficult or time-consuming, and the term was retained in English because it is important to local mobilisations and debates.

Une justice mobilitaire, des lectures concurrentielles

Mobility justice, competing interpretations

La mobilité quotidienne[1] s’inscrit au carrefour du (dys)fonctionnement de nos sociétés contemporaines (Bourdin, 2005 ; Orfeuil et Ripoll, 2015). Rien d’étonnant donc à ce qu’une justice mobilitaire (mobility justice) se soit développée dans la littérature sous le poids de la sociologie anglophone (Cresswell, 2006) puis de Mimi Sheller (Sheller, 2018a). Ce concept synthétise les enjeux des courants de recherche sur « l’équité des transports » et la « justice des transports » (Verlinghieri et Schwanen, 2020), eux-mêmes intéressés par des questions de justice spatiale (Soja, 2009). Synthétiquement, il vise à éclairer l’interdépendance entre les rapports de pouvoir et la production d’inégales formes de mobilités et d’immobilités, depuis l’échelle des corps humains jusqu’à celle de la planète (Sheller, 2018b).

Daily mobility[1] stands at the point where the (dys)functions of our contemporary societies intersect (Bourdin, 2005; Orfeuil and Ripoll, 2015). It is hardly surprising, then, that mobility justice developed in the literature under the influence first of Anglophone sociology (Cresswell, 2006) and then of Mimi Sheller (Sheller, 2018a). The concept of mobility justice encapsulates the issues at stake in the research currents on “transport equity” and “transport justice” (Verlinghieri and Schwanen, 2020), which are themselves concerned with questions of spatial justice (Soja, 2009). In short, it aims to cast light on the interdependence between power relations and the production of unequal forms of mobilities and immobilities, ranging from the scale of individual human bodies to the planet as a whole (Sheller, 2018b).

Le concept de justice mobilitaire a pour avantage d’offrir un recul par rapport à des approches trop objectivantes des déplacements individuels, popularisées en géographie des transports. Il laisse une plus ample place à la prise en compte de la dimension socialement construite de la mobilité (Massot et Orfeuil, 2005). Plus spécifiquement, des travaux révèlent que les différentes classes sociales ne sont pas également disposées à faire valoir et à légitimer leurs déplacements (Wagner, 2010 ; Rousseau, 2008). Puisqu’elle est un enjeu de luttes (Orfeuil et Ripoll, 2019, p. 121-124), tout porte à croire que la mobilité répond elle aussi à des « conceptions différentes, souvent contradictoires, voire conflictuelles, du “juste” et de “l’injuste” » (Gervais-Lambony et Dufaux, 2009, p. 4).

The value of the notion of mobility justice is that it constitutes a step back from the overly objectifying approaches to individual travel popular in transport geography. It gives greater consideration to the socially constructed dimension of mobility (Massot and Orfeuil, 2005). More specifically, research has shown disparities in the willingness of different social classes to assert and legitimise their rights to movement (Wagner, 2010; Rousseau, 2008). Given that mobility is a source of conflicts (Orfeuil and Ripoll, 2019, p. 121-124), there is every reason to believe that it too reflects “different, often contradictory, even conflicting conceptions of what is ‘fair’ and what is ‘unfair’” (Gervais-Lambony and Dufaux, 2009, p. 4).

Pourtant, la littérature – en géographie comme en sociologie – s’est jusqu’ici montrée timide sur l’usage de la justice mobilitaire pour éclairer des situations où se jouent des lectures concurrentes d’une « juste » manière de se déplacer. Cela est d’autant plus surprenant que les frictions entre enjeux de mobilité environnementaux, d’une part, et sociaux, d’autre part, se creusent dans les discours politiques ou institutionnels (Gallez, 2015, p. 58). Afin de pallier ce manque, le présent article se saisit d’une mobilisation autour d’un projet infrastructurel autoroutier pour décrypter l’opposition entre deux associations adversaires. Pour l’une, réfractaire à l’aménagement, la lutte s’inscrit dans la littérature sur les grands projets inutiles et imposés (GPII), dans la mesure où ses membres cherchent à se défaire de l’accusation de ne poursuivre que des intérêts privés (Grisoni, 2015 ; Sébastien, 2013). Pour l’autre, favorable au nouvel aménagement, il s’agit de négocier une position plus délicate, dans le sillage des élu∙e∙s du territoire, mais méfiante quant à leur programme politique. Ensemble, ces associations remettent en cause la « vision transcendantale de l’intérêt général » (Sébastien, 2016), dont les contours apparaissent plus que jamais à géométrie variable.

Yet the literature–in geography and sociology alike–has so far proved coy about using mobility justice to shed light on situations where competing interpretations of a “fair” way of getting around are at play. This is all the more surprising given the growing friction between environmental and social mobility issues in political and institutional discourse (Gallez, 2015, p. 58). To make up for this shortcoming, this article uses a protest movement around a motorway infrastructure project to decipher the opposition between two rival civil society organisations (CSO). For one group, which is opposed to the plan, the struggle is part of the literature on large, unnecessary, top-down projects, insofar as its members want to avoid the accusation that they are pursuing only private interests (Grisoni, 2015; Sébastien, 2013). The other group, which supports the new development, has a trickier path to negotiate, which entails supporting the area’s elected representatives while remaining wary of their political agenda. Together, these CSOs challenge the “transcendental vision of the general interest” (Sébastien, 2016), a vision that appears to be becoming ever more fluid in its outlines.

Parce que ce travail prend place dans l’espace géographique, cet article s’inspire du renouvellement des travaux attentifs à la dimension spatiale des mobilisations (Auyero, 2005 ; Hmed, 2020 ; Dechézelles et Olive, 2019), dont la mobilité est une composante essentielle. En réencastrant la contestation dans la matérialité de son territoire, il s’agit de prêter attention à des perceptions de la justice mobilitaire qui s’appuient sur des ressources (socio)spatiales différenciées et en témoignent ?

Because this work takes place in geographical space, this article is inspired by the revival of research into the spatial dimension of mobilisation (Auyero, 2005; Hmed, 2020; Dechézelles and Olive, 2019), of which mobility is an essential component. By re-embedding the protest in the materiality of its territory, it seeks to pay attention to perceptions of mobility justice that are based upon and reflect differentiated (socio)spatial resources.

L’interminable carrière institutionnelle du désenclavement du Chablais

The interminable institutional history of the disenclavement of the Chablais region

« Une chose est certaine, si un recours est déposé par la ville de Genève, nous lancerons des actions coup de poing pour bloquer Genève dans des endroits stratégiques à des heures de pointe et nous appellerons toutes les Chablaisiennes et les Chablaisiens à nous rejoindre ainsi que tous les élus du Chablais avec leur écharpe bleu, blanc, rouge sur le territoire helvétique !!! » (association Oui au désenclavement du Chablais, en février 2020)

“One thing is sure, if the City of Geneva lodges an appeal, we will take hard-hitting measures to blockade Geneva in strategic places at rush hour and we will be calling on all the people of Chablais to join us, as well as all the elected representatives of Chablais with their blue, white and red scarves on Swiss territory!!!” (association Oui au désenclavement du Chablais, February 2020)

Ces propos, publiés sur les réseaux sociaux par l’association Oui au désenclavement du Chablais[2] en février 2020, donnent le ton de la mobilisation qui rythme le nord de la Haute-Savoie depuis déjà 25 ans. Quelques mois plus tôt, le 24 décembre 2019, le Premier ministre Édouard Philippe décrète l’utilité publique (DUP) de la liaison autoroutière A412, longue de 16,5 km, entre les communes de Thonon-les-Bains (« Thonon » dans la suite de l’article) et de Machilly, proche d’Annemasse (voir figure 1). Le projet succède à deux autres, n’ayant pas été réalisés, dont les DUP sont finalement annulées : une première en 1995, prise en défaut par des associations écologistes, une seconde en 2006, abandonnée pour des raisons budgétaires, puis échue en 2016. Cette troisième mouture prévoit une exploitation par un concessionnaire privé appuyé d’une subvention d’équilibre départementale de 100 millions d’euros, un montage qui cristallise localement les débats.

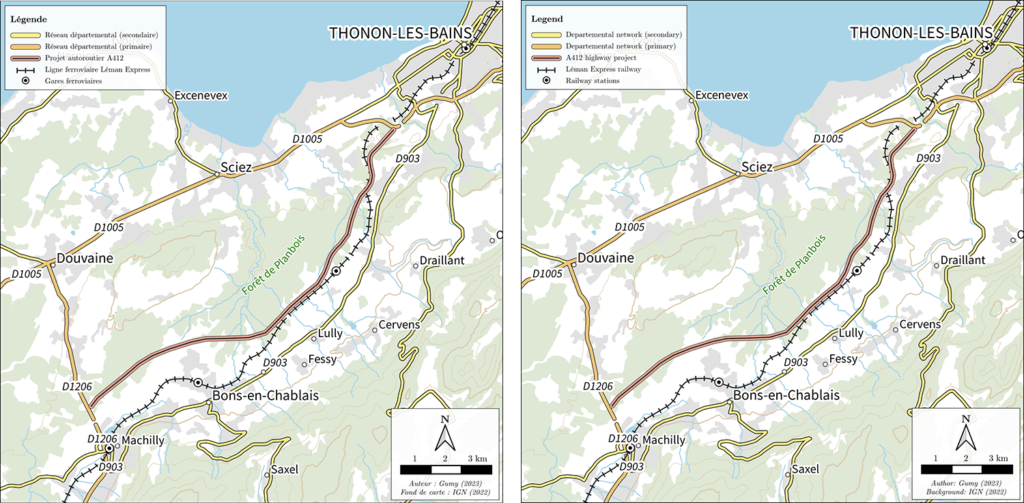

These words, posted on social media sites by the Oui au désenclavement du Chablais Association (Yes to the Disenclavement of Chablais)[2] in February 2020, set the tone for the campaign that has marked the north of Haute-Savoie for 25 years. A few months earlier, on 24 December 2019, Prime Minister Édouard Philippe decreed that the 16.5 km A412 motorway link between the towns of Thonon-les-Bains (“Thonon” in the rest of this article) and Machilly, near Annemasse, was a public interest project (DUP) (see figure 1). The project follows on from two others, which were not implemented, whose DUPs were eventually cancelled: the first in 1995, which was challenged by environmental groups, and the second in 2006, which was abandoned for financial reasons and then expired in 2016. The plan is that this third incarnation will be operated by a private contractor supported by a €100 million balancing subsidy from the département, a package that has polarised local debate.

Figure 1 : plan de situation du projet d’A412 et du Léman Express. Réalisation : Alexis Gumy (2023) ; fond de carte : IGN (2022)

Figure 1: Location map of the A412 and Léman Express projects. Produced by: Alexis Gumy (2023); background map: IGN (2022)

Ce nouveau projet, au tracé inchangé par rapport aux précédents et jouxtant des hameaux peu urbanisés et des zones forestières, s’inscrit dans un territoire particulièrement dynamique. Entre 2013 et 2019, la population dans l’aire d’attraction des villes de Genève et d’Annemasse s’accroît de 1,9 %, soit plus encore qu’en Haute-Savoie où ce taux est déjà supérieur à la moyenne nationale (1,2 %, contre 0,4 % en France métropolitaine)[3]. Cette croissance démographique s’explique notamment par l’attractivité du marché de l’emploi helvétique, celui-ci captant 34,3 % de la population active de Thonon Agglomération en 2018 et 49,8 % de celle d’Annemasse-les-Voirons Agglomération. Bien qu’une majorité de frontalier∙ère∙s appartiennent aux catégories socioprofessionnelles dites « intermédiaires » (31,2 %), leurs salaires médians (3 310 € par mois) imposent une sérieuse compétition sur le marché résidentiel local. En plus de tirer le coût de la vie vers le haut, l’emploi frontalier contribue à la saturation d’un réseau routier vieillissant. Le dossier de concertation publique de l’A412 annonce des trafics journaliers d’environ 15 000 véhicules ainsi qu’un taux de poids lourds de 5 % sur les routes départementales aux abords du tracé (D903, D1005 et D1206).

This new project, which follows the same route as the previous versions and runs past sparsely populated hamlets and forested areas, is embedded in a particularly dynamic region. Between 2013 and 2019, the population in the Geneva and Annemasse catchment area grew by 1.9%, even more than in Haute-Savoie where the rate was already above the national average (1.2%, compared with 0.4% in metropolitan France).[3] This demographic growth is due in particular to the attractiveness of the Swiss job market, which accounted for 34.3% of the working population of the Thonon conurbation in 2018 and 49.8% of that of the Annemasse-les-Voirons conurbation. Although a majority (31.2%) of cross-border workers belong to the so-called intermediate socio-professional categories, their median salaries (€3,310 per month) make the local residential market highly competitive. As well as pushing up the cost of living, cross-border employment contributes to congestion on an ageing road network. The public consultation documents for the A412 forecast daily traffic of around 15,000 vehicles and a heavy goods vehicle rate of 5% on the departmental roads along the route (D903, D1005 and D1206).

Le vendredi 14 février 2020, l’affaire prend une nouvelle tournure. Plusieurs associations, dont l’Association de concertation et de proposition pour l’aménagement et les transports (ACPAT), déposent un nouveau recours contre la troisième DUP de l’A412. Tout comme Europe Écologie-Les Verts, les communes frontalières de Genève et de Carouge, par leur pouvoir exécutif et au nom d’une convention liant la France et la Suisse (nommée « Espoo »), sont également signataires. Pour ces communes, le projet concurrencerait déloyalement le Léman Express, une nouvelle offre de RER transfrontalier inaugurée en décembre 2019, dans laquelle elles ont massivement investi. L’entrée en scène de collectivités allophones, s’opposant par voie juridique à une décision du gouvernement français, revêt localement une puissante charge symbolique.

On Friday 14 February 2020, the case took on a new twist. Several organisations, including the Association de concertation et de proposition pour l’aménagement et les transports (ACPAT; planning and transport consultation and proposal association), lodged a new appeal against the third DUP for the A412. Other signatories to this appeal were the French political party Europe Écologie-Les Verts and the executive authorities of the border municipalities of Geneva and Carouge on the grounds of an agreement between France and Switzerland (known as “Espoo”). These municipalities argued that the project would compete unfairly with the Léman Express, a new regional cross-border rail network (RER) service inaugurated in December 2019, in which they had invested heavily. The involvement of non-French communities in legal action to oppose a decision by the French government had a powerful symbolic impact at local level.

Alors que le Conseil d’État français ne s’était pas encore prononcé sur les recours contre la DUP de l’A412[4], j’ai pu enquêter auprès de l’association Désenclavement (les « pro-A412 ») et de l’ACPAT (les « anti-A412 »)[5], au plus fort de leur mobilisation. Cet article repose sur une campagne d’entretiens semi-directifs menés avec des habitant∙e∙s engagé∙e∙s pour leur territoire (N=12) et de représentant∙e∙s des pouvoirs publics proches du dossier (N=8), complétée par une analyse des documents de planification de l’A412[6]. Une première partie caractérise les associations engagées pour établir les conditions d’émergence de leurs revendications concurrentes. Une deuxième partie révèle par quels mécanismes l’A412 sert de levier pour contester l’aménagement du territoire chablaisien dans son ensemble. À la suite du recours de la ville de Genève, une dernière partie s’intéresse au processus de (re)spatialisation des argumentaires pour faire la preuve de l’(in)utilité publique de l’A412.

At a time when the French Conseil d’État had not yet ruled on the appeals against the A412’s DUP status,[4] I was able to survey the Désenclavement Association (“pro-A412”) and the ACPAT (“anti-A412”)[5] at the height of their respective mobilisations. This article is based on a series of semi-structured interviews conducted with locally engaged residents (N=12) and representatives of the public authorities with a close interest in the case (N=8), supplemented by an analysis of the A412 planning documents.[6] The first section describes the organisations involved, in order to establish the conditions under which their competing claims emerge. The second part reveals how the A412 was used as an instrument to challenge the development of the Chablais region as a whole. Following the appeal lodged by the City of Geneva, the final section looks at the process whereby the arguments used to demonstrate the public (in)utility of the A412 were re-spatialised.

Associations pro- et anti-désenclavement : projet du siècle, projet d’un autre siècle

Pro- and anti-disenclavement groups: project of the century, project of another century

Avant de se pencher sur la constitution et l’évolution de l’argumentaire des deux associations, il s’agit d’aborder leur sociologie. Bien qu’elles soient introduites ici l’une après l’autre, il convient de ne pas oublier que ces associations s’adonnent à un processus d’évaluation mutuelle (Mathieu, 2012), une « dynamique de couple » (Sommier, 2020) qui catalyse leurs conceptions différenciées de la justice mobilitaire. La composition des ressources d’autochtonie ainsi que les processus de socialisation à la mobilité font en particulier l’objet d’une attention approfondie.

Before looking at the construction and development of the two CSOs’ arguments, we need to look at their sociology. Although we introduce them here one after the other, it should not be forgotten that these organisations are engaged in a process of mutual evaluation (Mathieu, 2012), a “couples dynamic” (Sommier, 2020) that is a catalyst for their different conceptions of mobility justice. The composition of their “autochthony resources” and processes of socialisation to mobility are a focus of particular attention.

L’ACPAT : une variété de profils pour multiplier les arguments

ACPAT: a variety of profiles for a multiplicity of arguments

L’ACPAT est fondée en 1987 pour combattre le projet de « Transchablaisienne », prévoyant de compléter le réseau autoroutier autour du lac Léman. À la suite du retrait des collectivités suisses, c’est un projet écourté entre Annemasse et Thonon qui est déclaré d’utilité publique en 1995, avant que l’ACPAT ne contribue à son annulation deux ans plus tard. Comme le précise Josiane Favre[7], gérante d’une enseigne commerciale dans le Chablais, l’ACPAT profite de ce succès pour modifier son nom : anciennement Association contre le projet d’autoroute transchablaisienne, elle devient l’Association de concertation et de proposition pour l’aménagement et les transports. Ce changement témoigne d’une volonté de « monter en généralités » (Sébastien, 2013), en l’occurrence de s’éloigner d’une posture « vraiment anti-autoroute », peu rassembleuse localement, pour devenir force de proposition.

ACPAT was founded in 1987 to fight the “Transchablaisienne” project, which was intended to complete the motorway network around Lake Geneva. Following the Swiss authorities’ withdrawal from the plan, a shortened project between Annemasse and Thonon was granted public interest status in 1995, before ACPAT helped to bring about its cancellation two years later. As Josiane Favre,[7] manager of a retail chain in the Chablais region, explained, ACPAT took advantage of this success to change its name from Association contre le projet d’autoroute transchablaisienne (Against the Transchablaisienne motorway association) to Association de concertation et de proposition pour l’aménagement et les transports. The purpose of this change was to “broaden the appeal” (Sébastien, 2013), in other words to move away from a “really anti-motorway” stance, around which there was not much local unity, to become a source of proposals.

Cette ambition repose sur un travail d’expertise tacite (Meulemans et Tari, 2021) mené par l’association, perceptible à la quantité de littérature grise disponible sur son site officiel. Édith Morin, employée de la fonction publique en Suisse, s’appuie sur son expérience des espaces naturels pour tenir un discours critique à l’égard des autorités publiques, regrettant que « les arguments écologiques [soient] rarement écoutés ». Plus que par des positions identiques dans la hiérarchie socioprofessionnelle, les membres de l’ACPAT – souvent issu∙e∙s des petites classes moyennes, actif∙ve∙s ou retraité∙e∙s du secteur public, du commerce ou de l’agriculture – se rassemblent d’abord pour partager des activités (randonnée, chasse, équitation, etc.) liées au cadre naturel chablaisien. De ces activités, elles et ils puisent des ressources d’autochtonie, au sens d’un « stock de connaissances et [d’]un sentiment d’autorité à agir » (Sawicki, 2019) sur le projet d’A412. Ce n’est ainsi pas une coïncidence si l’ACPAT revendique d’avoir fédéré des associations de chasseur∙euse∙s, d’agriculteur∙ice∙s et d’habitant∙e∙s, pourtant peu connues pour s’entendre sur un aménagement consensuel du territoire.

This goal was based on a process of tacit evaluation (Meulemans and Tari, 2021) conducted by the organisation, as can be seen from the amount of grey literature available on its official website. Édith Morin, a Swiss civil servant, draws on her familiarity with natural areas in criticising the public authorities, regretting that “ecological arguments [are] rarely listened to”. More than because they share similar positions in the socio-economic hierarchy, ACPAT’s members–often lower-middle-class people either working in or retired from jobs in the public sector, commerce or farming–come together primarily to share activities (hiking, hunting, horse-riding, etc.) associated with the Chablais’ natural environment. From these activities, they draw resources of autochthony, understood as a “stock of knowledge and [a] sense of authority to act” (Sawicki, 2019) on the A412 project. It is therefore no coincidence that ACPAT claims to have brought together hunting and farming groups as well as local people, none of them famous for their capacity to agree on consensual land use planning.

L’ACPAT a pour réputation de camper un refus total du projet d’A412. C’est ce qu’explique Édith lorsqu’elle détaille les raisons qui l’ont poussée à quitter une association qui défendait une position plus nuancée de « oui, mais » :

ACPAT is known for its out-and-out rejection of the A412 project. This is what Édith explains when she describes why she left an organisation that advocated a more qualified “yes, but” position:

« Et moi je suis allée à une réunion publique, […] et puis je disais “mais en fait, on ne peut rien décider dans cette bande des 300 m ?” “Non, non, non, c’est le constructeur qui décide, nous, on fait une DUP sur cette bande et puis le constructeur décide où il se met”. Je dis “bah, en fait, pourquoi vous nous faites venir parce que de toute façon on n’a rien à dire !”, voilà, puis, j’avais été un petit peu agressive, et puis là il y avait des gens dans la salle et après ils étaient venus me trouver et dire “mais nous, on va lutter contre, carrément contre…”, parce que moi je ne pouvais même pas imaginer de dire “non”, c’était l’État, ce n’était pas possible de dire “non” […]. Et donc, après, bah, j’ai rencontré ces gens de l’ACPAT et puis on s’est dit : “bah nous ce n’était pas ‘oui, mais’, c’est ‘non’ !” Et là, ça a été quelque chose de totalement différent par rapport à l’association d’avant […]. » (Édith Morin, 57 ans, active dans la fonction publique suisse)

“And I went to a public meeting […] and then I said, ‘so in fact, we have no say in anything that happens in this 300 m strip?’ ‘No, no, no, it’s up to the contractor to decide. We’ll apply a DUP to this strip and then the contractor will decide where to put it.’ I said ‘right, so then why did you get us to come here, since there’s nothing we can do about it anyway’, right, and I’d been a bit aggressive, and so there were some people in the room who came over to me and said ‘well, we’re going to fight this, absolutely…’ because it didn’t even occur to me to say ‘no’, this was the government, there was no way you could say ‘no’ […]. And so, afterwards, well, I met these people from ACPAT and we agreed: ‘well, we weren’t going to say “yes”, we were absolutely going to say “no”!’ And that was something completely different from the previous organisation […].” (Édith Morin, 57, Swiss civil servant)

Pour Édith, la rencontre avec les membres de l’ACPAT est venue « bousculer [s]a socialisation antérieure » (Mathieu, 2012, p. 200) à l’action contestataire. Lors de mon enquête, elle me dit consacrer son temps libre à muscler l’argumentaire du recours, ses dispositions militantes s’actualisant au gré d’un engagement de tous les instants. C’est aussi que les militant·e·s de l’ACPAT sont plusieurs à participer à d’autres mouvements écologistes, l’exemple de Notre-Dame-des-Landes étant le plus récurrent, comme le plus valorisé. Sébastien Girod, actif dans le secteur primaire, me dit « piocher des idées » de ses rencontres avec le mouvement « No TAV » (Treno ad alta velocità, train à grande vitesse en italien), illustrant comment des « migrations militantes » (Grisoni, 2019) viennent diversifier le répertoire d’action à l’ACPAT.

For Édith, meeting the members of ACPAT “shook up the way she had previously been socialised” (Mathieu, 2012, p. 200) to protest action. During our interview, she told me that she spent her free time building up the case for the appeal, becoming increasingly more militant as her involvement grew. Many ACPAT activists are also engaged in other environmental movements, Notre-Dame-des-Landes being the most frequent and also the highest profile case. Sébastien Girod, who works in the primary sector, told me that he “picks up ideas” from his encounters with the “No TAV” movement (Treno ad alta velocità, Italian for high-speed train), illustrating how ACPAT’s range of action gains diversity through “activist migrations” (Grisoni, 2019).

L’association Désenclavement : des trajectoires mobiles pour défendre la route

The Désenclavement Association: members with a pro-road history

La volonté de s’inspirer d’exemples de mobilisations advenant hors du Chablais est loin d’être partagée par les 200 cotisant·e·s de l’association Désenclavement, surtout chez ses membres fondateurs qui sont encore aujourd’hui les plus actifs[8]. Comme l’explique Patrice Mollard, un des quelques membres à travailler dans le domaine du bâtiment et des travaux publics, l’association est avant tout « un réseau de connaissances, un réseau d’amis » qui s’investit prioritairement sur les scènes locales.

The wish to draw inspiration from examples of protest movements outside the Chablais is far from shared by the 200 members of Désenclavement, especially the CSO’s founding members who are still the most active today.[8] As Patrice Mollard, one of the few members who work in the building and public works sector, explains, the organisation is mainly “a network of acquaintances, a network of friends” who are primarily interested in local issues.

Patrice raconte la manière dont, au lendemain de l’annulation de la première DUP du projet d’A412 (dont les « belligérants » de l’ACPAT, comme il les surnomme, sont pour partie responsables) naît l’association nommée « Oui au contournement de Thonon, oui au désenclavement du Chablais ». Elle remporte à son tour une victoire importante lorsqu’est acté, en 2004, le contournement routier de Thonon, conduisant là aussi à modifier le nom de l’association. Patrice revendique un rôle « d’accélérateur » dans ce dossier, qu’il convoque comme une démonstration des promesses de décongestion associées à l’A412 : « on se demande comment est-ce qu’on pourrait encore vivre sans le contournement de Thonon […] qui [a] chang[é] la vie de toute une population ».

Patrice tells the story of how, the day after the first DUP for the A412 project was cancelled (for which the ACPAT “radicals”, as he calls them, were partly responsible), the “Oui au contournement de Thonon, oui au désenclavement du Chablais” (Yes to the Thonon bypass, yes to the disenclavement the Chablais region) Association was set up. It also scored a major victory when the Thonon bypass was approved in 2004, which also led to a change in the association’s name. Patrice claims to have played a role as an “accelerant” in this project, which he sees as a demonstration of the promises of traffic reduction associated with the A412: “We wonder how we could live without the Thonon bypass […] which has changed the lives of a whole population.”

Pour les membres de Désenclavement, l’engagement en faveur de l’A412 s’inscrit dans la continuité de parcours biographiques similaires. Tous ont connu une trajectoire professionnelle (et sociale) ascendante dans le domaine industriel pour occuper, actuellement ou avant leur retraite, des positions de cadres ou de chefs d’entreprise indépendants. Le cas de Gérard Mouchet, retraité de l’agroalimentaire, est exemplaire de cette trajectoire. Né dans le Haut-Chablais à la fin des années 1940, il passe son enfance dans des territoires d’outre-mer du fait de l’engagement militaire de son père. À son retour, il a alors 18 ans, il commence sa carrière en tant que commercial puis gravit les échelons à la faveur de bons services rendus à sa hiérarchie pour « fini[r] cadre, quand même ». Comme d’autres membres de l’association, il attribue sa réussite professionnelle à sa capacité à faire preuve d’une (auto)mobilité intensive, à « s’être bien bougé ». La notion de « trajectoire mobilitaire » de long cours (Cailly et al., 2020) permet de comprendre la façon dont ces militants associent leur ascension professionnelle aux possibilités offertes par le réseau routier français, au point d’avoir développé des dispositions se réactivant pour défendre de telles infrastructures.

For the members of Désenclavement, the support for the A412 derives from similar life paths. All of them have advanced professionally (and socially) in the industrial sector and already–or will before they retire–occupy managerial positions or run their own businesses. The career of Gérard Mouchet, a retiree from the agri-food industry, is typical of this trajectory. Born in Haut-Chablais in the late 1940s, he spent his childhood in France’s overseas territories because of his father’s military career. When he returned, aged 18, he began work as a salesman, then rose through the ranks by serving his bosses well to “end up as an executive nonetheless”. Like other members of the organisation, he attributes his career success to his ability to demonstrate intense (self)mobility, to “having moved around a lot”. The notion of a long-term “mobility trajectory” (Cailly et al., 2020) is a way to understand how these activists associate their career advancement with the opportunities offered by the French road system, to the point that they have ingrained attitudes that are reactivated in support of these infrastructures.

L’association Désenclavement témoigne donc d’une forte homogénéité sociale. Celle-ci ne se résume pas à la composition de l’association, mais conditionne aussi son répertoire d’action « induis[a]nt une exclusion des postulants par trop différents » (Mathieu, 2012, p. 214-215). Les militants racontent, sur un registre oscillant entre fierté et nostalgie, comment ils ont multiplié des actions qui « font du bruit » sur les scènes politique et médiatique locales : blocage en gare de Bellegarde (1999), édification d’un mur à la frontière de Saint-Gingolph (1999), performance où des membres se suspendent au-dessus du contournement de Thonon (2013), etc. Christian Grillet, retraité du secteur industriel, constate que « ça ne se pourrait plus maintenant », à cause d’une « atmosphère générale » tendue et d’une vigilance accrue des forces de l’ordre. Les entretiens laissent alors transparaître les négociations « dans la bonne humeur » entre l’association et l’autorité policière, une manière pour les membres de contrecarrer l’appauvrissement de ce répertoire d’action.

Désenclavement is therefore very socially homogeneous. This homogeneity is not limited to the group’s composition, but also influences the nature of its activities “leading to the exclusion of applicants who are too different” (Mathieu, 2012, p. 214-215). The activists describe, in a tone that fluctuates between pride and nostalgia, how they have escalated the number of actions that have “made a splash” on the local political and media scene: blockades at Bellegarde train station (1999), the construction of a wall at the Saint-Gingolph border (1999), a stunt in which members suspended themselves above the Thonon bypass (2013), and so on. Christian Grillet, a former industrial sector worker, notes that “it might not happen now”, because of increased tension in the “general atmosphere” and greater police vigilance. The interviews reveal “good-humoured” negotiations between the organisation and the police authority, a way for the members to counteract the impoverishment of its range of action.

Enfin, Désenclavement entreprend un travail de publicisation par sa présence à diverses élections chablaisiennes, que ce soit aux législatives de 2012, aux sénatoriales de 2014 ou, plus récemment, aux départementales de 2021. Ils occupent ainsi une position de garants du débat politique, s’assurant de l’inscription du projet d’A412 au programme de leurs concurrent∙e∙s. De plus, ils officialisent les ressources d’autochtonie de l’association par une mise en récit de la persévérance d’un groupe d’enfants « du coin », menant un combat sans relâche pour que les promesses du désenclavement soient finalement tenues.

Lastly, Désenclavement works to raise public awareness by participating in different elections in the Chablais region, including the 2012 parliamentary elections, the 2014 Senate elections and, more recently, the 2021 departmental elections. In this way, they seek to position themselves as guarantors of political debate, ensuring that the A412 project remains on their adversaries’ agenda. Moreover, they legitimise the CSO’s embeddedness in indigenous life by telling the story of the perseverance of a group of “local” children in leading a relentless battle to ensure that the promises of disenclavement are ultimately kept.

Ces descriptions pourraient faire oublier que les associations, même si elles sont en concurrence, partagent des adversaires communs : les élu∙e∙s du Chablais et les représentant∙e∙s de l’État. Tantôt accusé·e·s de ne faire du désenclavement qu’une promesse de campagne sans lendemain, tantôt présenté·e·s comme une vieille garde incapable de servir les objectifs de la transition écologique, l’autorité publique se retrouve propulsée au centre d’une mobilisation à deux visages. Ce procédé rappelle ce que Marie-Hélène Bacqué et ses collègues (2016) décrivent comme des tentatives (ici concurrentielles) d’exercer un contrôle sur un espace de vie partagé, dans le but de le (contre)aménager selon des définitions différenciées de « l’enclavement ».

These descriptions risk blinding us to the fact that the organisations, although in competition, share common adversaries: the elected representatives of the Chablais and government officials. Whether accused of using the disenclavement of the region purely as a campaign promise with no follow-through, or presented as an old guard incapable of pursuing the objectives of ecological transition, the authorities find themselves under attack on both flanks. This process is reminiscent of what Marie-Hélène Bacqué and her colleagues (2016) describe as attempts (in this case competing attempts) to exert control over a shared living space, with the aim of promulgating plans and counter-plans for it based on different definitions of “enclavement”.

Définir l’enclavement : le rôle incertain de l’éloignement sur le territoire

Defining enclavement: the ambiguous role of territorial remoteness

La mobilisation autour de l’A412 peut être considérée comme une entreprise de « politisation du proche » (Dechézelles et Olive, 2019), pour souligner le travail de certification d’un capital d’autochtonie auquel s’adonnent les militant∙e∙s pour légitimer leurs actions (Sawicki, 2019 ; Dechézelles, 2019). L’ACPAT et Désenclavement, en redéfinissant l’enclavement du Chablais selon leurs propres termes, traduisent des aspirations différenciées pour un territoire conforme à de « justes » mobilités.

The mobilisation around the A412 can be seen as an attempt to “politicise the local” (Dechézelles and Olive, 2019), a way for activists on both sides to emphasise the effort to certify indigenous capital in order to legitimise their actions (Sawicki, 2019; Dechézelles, 2019). By redefining the isolation of the Chablais in their own terms, ACPAT and Désenclavement reflect different aspirations for a region that are characterised by “fair” mobilities.

Une récupération partisane du mythe des effets structurants du transport

Hijacking the myth of the structuring effects of transport for partisan ends

Appréhender le combat sur l’A412 entre, d’un côté, une association écologiste exclusivement portée sur les modes de transport alternatifs à l’automobile et, de l’autre, un lobby d’automobilistes convaincus appelle certaines réserves. Méthodologiquement, la rhétorique de la « guerre des transports » reproduit un discours essentialisant sur l’automobile, plus qu’elle n’éclaire en quoi certaines formes d’automobilisme sont jugées problématiques (Reigner, 2013 ; Demoli et Lannoy, 2019, p.78). Empiriquement, les discours sur le terrain sont loin de défendre un désenclavement uniquement tourné vers l’un ou l’autre des modes de transport. L’affrontement entre pro- et anti-désenclavement ne s’organise donc pas tant autour de la dépendance ou de la congestion automobiles locales, que sur les manières d’y remédier. C’est ce qu’Édith suggère dans l’extrait suivant :

The attempt to understand the battle over the A412 between, on the one hand, an environmental group focused exclusively on modes of transport other than the car and, on the other, a lobby of convinced motorists, calls for certain reservations. Methodologically, the rhetoric of the “transport war” reproduces an essentialising discourse around the car, rather than clarifying why certain forms of automobile use are considered problematic (Reigner, 2013; Demoli and Lannoy, 2019, p. 78). Empirically, what is being said on the ground is in no way an argument for disenclaving the region solely to one or other mode of transport. The confrontation between pro- and anti-A412 groups is therefore not so much about local car dependency or congestion, as about how to mitigate them. This is what Édith suggests in the following extract:

« Je… je… je n’arrive pas à comprendre qu’ils ne comprennent pas. Qu’ils aient envie de prendre leur voiture, etc., bon, bah, ça je peux comprendre, qu’ils ne sachent pas faire sans la voiture, c’est vrai que par ici c’est plus compliqué. Mais… mais qu’ils ne comprennent pas qu’une nouvelle route ne va pas résoudre le problème, ça, ça m’hallucine. » (Édith Morin, 57 ans, active dans la fonction publique suisse)

“I… I… I can’t understand how they don’t understand. That they want to take their cars, etc., well, that I can understand, that they don’t know how to do without a car, it’s true that around here it’s more complicated. But… the fact that they don’t understand that a new road isn’t going to solve the problem is mind-boggling.” (Édith Morin, 57, Swiss civil servant)

Dans le but de mettre en cause le projet d’A412, l’ACPAT et Désenclavement récupèrent de façon concurrente et partisane, socialement et spatialement située, le « mythe des effets structurants » du transport (Offner, 1993). Dans son article fondateur, Jean-Marc Offner suggère d’appréhender toute nouvelle offre de transport en tant « [qu’]instrument potentiel de stratégies des acteurs territoriaux » (ibid., p. 238). Il montre, sous l’a priori qu’une augmentation de cette offre conduit mécaniquement à un « meilleur » urbanisme, que ce « mythe de l’effet autorise et légitime l’action du décideur » (ibid., p. 241). Bien que ce mythe ait largement été discuté depuis, il a encore récemment été utilisé par son auteur pour critiquer la tendance de l’action publique, au moment de justifier des grands projets urbains, à se reposer sur des arguments de vente trop simplificateurs (Offner et al., 2014). Face à l’inaction des autorités locales, les membres de l’ACPAT et de Désenclavement proposent une relecture de ce mythe à même, respectivement, de confronter ou de conforter le besoin autoroutier.

With the aim of challenging the A412 project, ACPAT and Désenclavement are reviving the “myth of the structuring effects” of transport (Offner, 1993) in a competitive, partisan, socially and spatially situated way. In his seminal article, Jean-Marc Offner suggests that all new transport services should be seen as “[a] potential instrument of local players’ strategies” (ibid., p. 238). On the premise that an increase in supply automatically leads to “better” urban planning, he shows that this “myth of effect authorises and legitimises the actions of decision-makers” (ibid., p. 241). Although this myth has since been widely contested, it has recently been cited by the author to criticise the tendency of public action to rely on oversimplified selling points when justifying major urban projects (Offner et al., 2014). Faced with inaction by the local authorities, the members of ACPAT and Désenclavement propose a rereading of this myth in order, respectively, to contest or advocate the need for motorways.

Les pro-désenclavement développent un discours pragmatique pour justifier le besoin autoroutier. En premier lieu, l’autoroute garantirait des gains de temps, d’autant plus évidents que les membres se confrontent souvent à la congestion automobile chablaisienne. En second lieu, la nouvelle infrastructure serait bénéfique à l’écologie en fluidifiant le trafic local, les véhicules contournant des villages actuellement engorgés. Si ces manœuvres rappellent les opérations « d’accréditation » repérées dans la littérature (Traïni, 2005), elles sont ici plus vindicatives tant les militants tentent de se substituer à des autorités jugées défaillantes. Pour Patrice, l’association Désenclavement « fait le travail » des élu∙e∙s, peu importe si ces dernier∙ère∙s ne sont pas « toujours contents du résultat ».

Those in favour of the disenclavement of the region use pragmatic arguments to justify the need for a motorway. Firstly, the motorway would bring guaranteed time savings, which is all the clearer insofar as members often have to contend with traffic congestion in the Chablais region. Secondly, the new infrastructure would benefit the environment by easing local traffic, as vehicles would bypass villages that are currently congested. While these manoeuvres are reminiscent of the “accreditation” operations present in the literature (Traïni, 2005), in this case they are more vindictive as the activists are seeking to replace authorities that are deemed to be failing. For Patrice, Désenclavement is “doing the job” of elected officials, regardless of the fact that the latter are “not always happy with the result”.

Du côté de l’ACPAT, les militant∙e∙s se montrent réservé∙e∙s quant à la capacité d’un projet « du siècle passé » à résorber des problèmes structurels de circulation. Pour la justifier, les qualificatifs « d’appel d’air » ou « d’aspirateur à bagnoles » se multiplient, tandis que les références à des études scientifiques démontrent la saturation irrémédiable du réseau (auto)routier. Dans cette perspective, les membres accusent les ingénieur∙e∙s du projet de promesses fallacieuses de réductions de charges sur les routes départementales environnantes. Un extrait d’entretien avec Josiane éclaire ces allégations :

On the ACPAT side, the activists are dubious about the capacity of a “last-century” project to solve structural traffic problems. To support this view, they make liberal use of terms such as “pull factor” or “automobile magnet”, along with references to scientific studies that demonstrate the irremediable saturation of the road/motorway network. From this angle, the members accuse the project engineers of making false promises about traffic reductions on the nearby departmental roads. An extract from an interview with Josiane sheds light on these allegations:

« Alors l’étude d’impact, elle est super bien faite parce que l’étude d’impact réussit à montrer qu’on a besoin de l’autoroute. […] c’était bien vu parce qu’en fait les mesures ont été faites au moment où la liaison entre […] les Eaux-Vives en Suisse, Annemasse en France, était interrompue parce qu’on construisait le Léman Express. Donc forcément, du jour au lendemain quand la liaison a été interrompue on a rebalancé tout un tas de gens qui prenaient le train, on les a rebalancé dans leur voiture et sur la route, ça fait augmenter le trafic, donc si on fait les mesures à ce moment-là, forcément qu’il y a des embouteillages et forcément qu’il n’y a personne dans le train puisqu’il ne va plus nulle part ! C’était bien vu, voilà. […] Donc, c’est pour ça que l’étude d’impact est complètement fausse quoi. » (Josiane Favre, 59 ans, active gérante d’une enseigne commerciale)

“The impact study is very well done because it shows that we need the motorway. […] It was a clever idea because in fact the measurements were taken at a time when the link between […] les Eaux-Vives in Switzerland and Annemasse in France was interrupted because the Léman Express was being built. So inevitably, from one day to the next, when the link was interrupted, a whole bunch of people who had been taking the train were shunted back into their cars and onto the roads, which increases traffic. So, if you take a measurement at that point, you’re bound to have traffic jams and you’re bound to have no one on the train because it’s not going anywhere! It was a clever idea, that’s all. […] So, I mean that’s why the impact study is completely wrong.” (Josiane Favre, aged 59, working as a retail chain manager)

Cet exemple n’est pas isolé et témoigne de la capacité des militant·e·s à se réapproprier, grâce à leurs ressources d’autochtonie, un ensemble de savoirs habituellement réservés à des ingénieur∙e∙s spécialisé∙e∙s[9].

This is not an isolated example and testifies to the ability of activists to draw upon their indigenous resources to acquire knowledge that is usually restricted to specialist engineers[9].

En définitive, ces interactions conflictuelles ouvrent la voie à une critique plus générale des politiques de mobilité dans le Chablais, en lien avec sa situation « enclavée ». La récupération du mythe des effets structurants du transport fonctionne, pour les associations, comme une mise à niveau avec l’autorité publique, l’objectif étant de dire ce qui n’est pas « juste », au double sens de l’injustice et de l’incorrect.

Ultimately, these conflicting interactions pave the way for a more general critique of mobility policies in the Chablais, in relation to its “isolated” condition. Borrowing the myth of the structuring effects of transport enables the CSOs to put themselves on a par with the authorities, the objective being to say what is not “right”, in the dual sense of being unfair and being incorrect.

Village gaulois, trésor caché : un Chablais aux multiples facettes

Gallic village, hidden treasure: a multi-faceted Chablais

Deux conceptions d’un territoire chablaisien conforme aux attentes des habitant·e·s se font face. La première, imposée par l’ACPAT, est résumée par Josiane quand elle dit « par[tir] du principe qu’on n’est pas enclavé, on est loin. C’est géographique, c’est fait comme ça. » Pour cette association, l’enclavement constitue une propriété intrinsèque du territoire, aussi bien naturalisée que valorisée. Pour Sébastien, la préservation du patrimoine local – un « trésor méconnu » selon lui – est indispensable face à la menace autoroutière. Dans son cas, la mobilisation contre le désenclavement revêt une portée « exploratoire » (Dechézelles et Olive, 2016), c’est-à-dire l’occasion de (re)découvrir les vertus du proche et surtout de les faire (re)découvrir à d’autres. D’après lui, « on ne défend bien que ce qu’on connaît », raison pour laquelle il organise des marches pédagogiques pour sensibiliser les habitant·e·s à leur cadre de vie dans l’espoir de susciter leur engagement. La consécration de l’enclavement en « capital patrimonial » (Sébastien, 2013), loin de traduire une approche conservatrice du Chablais, s’accompagne donc d’un travail de publicisation mené par l’ACPAT. Par ses actions, elle développe un argumentaire de valorisation des relations sociales ou spatiales dans le proche, autrement dit une justice mobilitaire libérée d’une compréhension productiviste du territoire.

There are two opposing visions of the kind of Chablais region that its residents want. The first, espoused by ACPAT, is summed up by Josiane when she talks about “starting from the principle that we’re not isolated, we’re remote. It’s geographical, that’s just the way it is.” For her organisation, remoteness is an intrinsic property of the region, one that is both naturalised and treasured. For Sébastien, preserving the local heritage–an “underappreciated treasure” in his view–is essential in view of the threat from the motorway. In his case, the mobilisation against the disenclavement of the region has an “exploratory” dimension (Dechézelles and Olive, 2016), i.e. it offers an opportunity to (re)discover the virtues of the local area and, above all, to help others (re)discover them. In his view, “you can only defend what you know”, which is why he organises educational walks with residents to raise their awareness of their local environment, in the hope of stimulating them to engage. Far from representing a conservative approach to the Chablais region, the fact that the region is an enclave is recognised as a “heritage asset” (Sébastien, 2013) and is emphasised in ACPAT’s communication. Through its actions, it develops an argument for the enhancement of social or spatial relationships in the local area, in other words a form of mobility justice that is devoid of a productivist perception of the region.

Du côté de Désenclavement, les membres regrettent tous l’éloignement que le Chablais hérite de son développement sur un modèle de « village gaulois ». D’une part, Didier Magnin, jeune retraité du secteur tertiaire en Suisse, déplore le fonctionnement des élections locales sur un mode d’entre-soi que leurs candidatures n’ont pas su déjouer, au point que les projets d’aménagements fassent toujours l’objet d’une consultation « des amis des amis » des élu·e·s. D’autre part, les membres regrettent la position du territoire chablaisien sur la carte départementale des investissements publics, les politiques redistributives favorisant systématiquement d’autres agglomérations plus attractives (en particulier Annecy). Didier parle à ce titre de « sachets de sucre » pour décrire les rares investissements départementaux à Thonon, faisant de la subvention d’équilibre une chance à ne pas manquer. Pour l’association, l’enclavement du Chablais relève du stigmate territorial, c’est-à-dire qu’il résulte d’occasions manquées d’en faire un territoire attractif, libéré de sa dépendance à la Suisse. Elle revendique alors le droit pour tou∙te∙s les chablaisien∙ne∙s à se déplacer librement, facilement et, surtout, en voiture sur l’ensemble du département.

As for Désenclavement, the members all regret the remoteness that the Chablais has inherited from its development on a “Gallic village” model. On the one hand, Didier Magnin, a young retiree from the tertiary sector in Switzerland, deplores the fact that local elections are run on the basis of an “insider” system that their candidates have not been able to overcome, to the extent that development projects are always subject to consultation “with friends of friends” of the elected representatives. On the other hand, the members also regret the Chablais region’s place on the departmental map of public investment, with redistribution policies systematically favouring other, more attractive conurbations (in particular Annecy). Didier refers to the rare departmental investments in Thonon as “sweeteners”, with the result that the balancing subsidy is seen as an opportunity not to be missed. For Désenclavement, the isolation of the Chablais is the product of territorial stigma, i.e., missed opportunities to make it an attractive area, free from its dependence on Switzerland. The CSO thus demands that all inhabitants of the Chablais should have the right to travel freely, easily and, above all, by car throughout the département.

Ces éléments montrent comment l’ACPAT et Désenclavement se livrent à une entreprise de (re)définition de « l’enclavement » chablaisien autour du projet d’A412. Plus que promouvoir ou critiquer l’automobilisme, les militant∙e∙s soulignent en quoi l’infrastructure est en (dés)accord avec leurs modes de vie et leurs réseaux (routiers, mais aussi sociaux) du quotidien. Pour les premier∙ère∙s, l’A412 viendrait étioler une ruralité valorisée et préservée dans le Chablais ; pour les seconds, elle permettrait de débrider le territoire afin d’affirmer son dynamisme économique et démographique. Chaque association souhaite certifier une « appropriation identitaire » concurrente du territoire, autrement dit associer une identité collective à l’espace contesté, ce qui « suppose sa pratique concrète, régulière et démonstrative » (Ripoll et Veschambre, 2005, p. 7). Aborder cette mobilisation sous l’angle de la justice mobilitaire signale ainsi les légitimités variables pour faire accepter un développement conforme du Chablais.

These factors show how ACPAT and Désenclavement redefine the “enclave” character of the Chablais region around the A412 project. Rather than promoting or attacking car use, the activists placed the emphasis on how the infrastructure is in or out of keeping with their lifestyles and their everyday networks, both roads and social networks. For ACPAT, the A412 would undermine the rural nature of the Chablais, which has so far been valued and preserved; for Désenclavement, it would unleash the region’s economic and demographic dynamism. Each organisation wishes to legitimise a competing “appropriation of territorial identity”, in other words to associate a collective identity with the contested space, which “presupposes its real, regular and demonstrative practice” (Ripoll and Veschambre, 2005, p. 7). Looking at this mobilisation from the point of view of mobility justice thus highlights the varying legitimacies involved in gaining acceptance for the development of the Chablais region.

L’irruption de la Municipalité de la commune de Genève – nommée ci-après « Genève » – participe alors d’un repositionnement original des associations sur la question de la portée fonctionnelle du projet d’A412. La dernière section du présent article rend compte du travail que mènent les associations pour concrétiser les enjeux autoroutiers à l’échelle la plus locale.

The emergence of the Municipality of Geneva–hereinafter referred to as “Geneva”–prompted the activist groups to adopt an original repositioning on the question of the functional scope of the A412 project. The final section of this article reports on the work carried out by the CSOs to bring motorway issues to the forefront at the most local level.

Inscrire l’autoroute dans le proche : entre création et réponse à des besoins

Embedding the motorway in the local: between creating and meeting needs

La mobilisation autour du projet d’A412 témoigne de l’intérêt à repérer des luttes concurrentielles au sein de la société civile pour explorer des tentatives d’imposer une définition singulière d’un problème public au-devant d’une collectivité. Loin d’avoir transformé en profondeur un débat vieux de 25 ans, le recours de Genève l’a manifestement fait entrer dans une nouvelle dimension pour plusieurs raisons. Tout d’abord, comme Patrice l’avoue à regret, le rayonnement symbolique genevois dans le Chablais confère à la ville suisse le pouvoir de peser sur les affaires politiques régionales. En parallèle, ce qu’il qualifie « d’ingérence suisse », la question de la souveraineté territoriale s’immisce dans le débat. Ensemble, ces aspects institutionnalisent la mobilisation pour contraindre les associations à s’aventurer dans un langage juridique parfois élaboré : au nom de quel(s) accord(s) une autorité suisse, membre de la coopération transfrontalière, peut-elle revendiquer un droit de recours sur le territoire français ? Enfin, ce recours implique un renouvellement de l’attention médiatique autour du projet qui s’étend, de façon inédite, jusqu’en Suisse. Pour ces raisons, la mobilisation autour de l’A412 acquiert un statut de controverse dans le proche, c’est-à-dire la mise en scène locale d’un désaccord à coups d’expertises officielles ou tacites, devant un tiers chargé d’arbitrer le différend (Tari, 2021, p.28). Les associations sont alors dans l’attente d’un verdict officiel de l’État pour consacrer les « plus justes » manières de se déplacer dans le territoire chablaisien.

The mobilisation around the A412 project demonstrates the value of identifying competing struggles within civil society in order to explore attempts to impose a single definition of a public problem on a community. Far from profoundly transforming a 25-year-old debate, the Geneva appeal has clearly taken it into a new dimension for a number of reasons. Firstly, as Patrice reluctantly admits, Geneva’s symbolic influence in the Chablais gives the Swiss city the power to influence regional political affairs. At the same time, it brings the issue of territorial sovereignty–what he describes as “Swiss interference”–into the debate. Together, these aspects institutionalise the mobilisation, forcing the CSOs to venture into sometimes sophisticated legal language: what agreement(s) can a Swiss authority, a member of a cross-border cooperation arrangement, cite in order to claim a right of appeal on French territory? Last but not least, this legal process has triggered a renewal of media attention around the project which, unprecedentedly, extends as far as Switzerland. For these reasons, the mobilisation around the A412 has acquired the status of a local-level controversy, i.e. the local staging of a dispute, including recourse to official or tacit expert opinions, before a third party with responsibility to arbitrate (Tari, 2021, p. 28). In other words, the CSOs are now waiting for an official verdict from the state to establish the “fairest” ways of moving around the Chablais region.

La position de Genève consiste à reprocher à l’itinéraire de l’A412 d’être trop similaire à celui du Léman Express, tout juste inauguré. Elle prend la forme d’un discours moralisateur, celui d’un rejet général de l’automobilisme, jusque-là évacué par l’ACPAT (et par Désenclavement). En réduisant la lutte à une opposition entre infrastructures routières et ferroviaires, Genève s’approche d’un rôle d’entrepreneur de morale (Mathieu, 2020). En disqualifiant les comportements des frontalier∙ère∙s à destination de son centre-ville, elle a précipité le débat vers le droit d’usage de l’autoroute. Pour répondre à l’arrivée d’un soutien inespéré (pour l’une) ou d’un adversaire inattendu (pour l’autre), l’ACPAT et l’association Désenclavement réinvestissent alors la dimension spatiale de l’A412.

Geneva’s argument is that the A412 route is too similar to that of the recently inaugurated Léman Express railway. It takes the form of a moralising discourse–based upon a general rejection of automobile use–that was hitherto dismissed by the ACPAT (and by Désenclavement). By reducing the conflict to a competition between road and rail infrastructure, Geneva has adopted a role close to that of a moral entrepreneur (Mathieu, 2020). By disparaging the practices of people living near the border seeking to access its city centre, it has tipped the debate towards the right of motorway use. In response to the arrival of an unhoped supporter (for one) or an unexpected adversary (for the other), ACPAT and Désenclavement have reverted to a focus on the spatial dimension of the A412.

La réaction est unanime parmi les membres de Désenclavement. Patrice l’illustre quand il me relate la fin d’un échange avec un journaliste suisse :

The reaction among Désenclavement members was unanimous. Patrice illustrates this when he tells me about the end of a conversation with a Swiss journalist:

« “[…] écoutez, monsieur, le train c’est une chose, la route c’en est une autre, et le Léman Express sauf à ce que vous me prouviez le contraire, il dessert Genève. L’autoroute, elle ne va pas desservir Genève parce qu’elle ne va pas à Genève. Donc faites un article une fois…” On milite pour désenclaver le Chablais, on ne milite pas pour désenclaver Genève. Voilà. » (Patrice Mollard, 54 ans, indépendant)

“‘[…] listen, my friend, the train is one thing, the road is another, and unless you can prove otherwise, the Léman Express serves Geneva. The motorway will not serve Geneva because it does not go to Geneva. So now write an article about that…’ We’re campaigning to open up the Chablais region, not to open up Geneva. And that’s it.” (Patrice Mollard, 54, self-employed)

Surpris que Genève se manifeste bien après la concertation publique de 2016, les militants lui reprochent de se mêler d’un débat qui ne la concerne pas et dont elle ne saisit pas les enjeux. Ils critiquent « l’impérialisme genevois » (Audikana et al., 2016), un point de vue partagé par un élu français déclarant que « Genève ne pense le reste du territoire que dans la relation que ces territoires ont à elle-même, pas dans leur existence propre ». Pourtant, la position de Genève contraint l’association à déployer un double argumentaire afin de disqualifier l’autorité publique suisse. D’une part, Patrice l’accuse de « ne pas balayer devant sa porte » en se montrant au fait des projets (auto)routiers du canton suisse. D’autre part, les membres se saisissent de la dimension locale du projet d’A412, auparavant laissée à l’ACPAT, pour prouver le besoin de « relier le Chablais au reste du département ». Ils défendent alors une position ambiguë, faisant coïncider une infrastructure de transport de transit avec des besoins internes au bassin chablaisien (aller au théâtre, chez le médecin, etc.), ce qui passe aussi par la délégitimation des allers-retours frontaliers à destination de Genève. Désormais focalisés sur le proche, ils se distinguent de leurs adversaires de l’ACPAT en désignant les populations en droit d’être désenclavées, en l’occurrence les chablaisien∙ne∙s n’étant pas employé∙e∙s en Suisse. L’arrivée de Genève dans le débat participe donc, pour Désenclavement, d’une (re)spatialisation de la portée fonctionnelle de l’A412 pour en justifier l’utilité publique.

Caught by surprise at Geneva entering the fray well after the public consultation in 2016, the activists criticise it for interfering in a debate that is none of its affair and that raises questions that it does not understand. They criticise “Geneva’s imperialism” (Audikana et al., 2016), a view shared by one French elected representative, who declared that “Geneva only thinks of the rest of the region in terms of the relationship between those regions and itself, not in terms of their own existence”. However, Geneva’s involvement has forced the organisation to come up with a dual argument in order to challenge the Swiss authority’s credibility. On the one hand, Patrice accuses it of “not putting its own house in order” by demonstrating familiarity with the Swiss canton’s road and motorway projects. On the other hand, the members have taken advantage of the local dimension of the A412 project, previously left to ACPAT, to demonstrate the need to “link the Chablais to the rest of the département”. They therefore advocate an ambiguous position, linking a transit infrastructure with needs within the Chablais area (trips to the theatre, the doctor’s surgery, etc.), which also entails delegitimising cross-border round trips to Geneva. Now shifting their focus to the local level, they distinguish themselves from their ACPAT opponents by designating which populations are entitled to greater accessibility, in this case inhabitants of Chablais who do not work in Switzerland. For Désenclavement, Geneva’s entry into the debate is therefore part of a process of (re)spatialising the A412’s functional scope in order to justify its public utility.

L’ACPAT accueille quant à elle la voix de Genève sur un tout autre mode. Un mécanisme de certification (Neveu, 2019) par substitution se donne à voir, c’est-à-dire le relais d’un discours écologiste inaudible dans le Chablais par une puissante collectivité de l’autre côté de la frontière. Certain∙e∙s militant∙e∙s, comme Édith ou Sébastien, disent attendre avec impatience une « remontée [de la question du projet d’A412] au niveau de la Confédération helvétique » dans l’espoir d’asseoir la légitimité de leurs arguments. L’association intègre donc le soutien genevois dans une stratégie de cumulation des recours à l’encontre du gouvernement français qui « n’a pas d’autre exemple […] où il a une telle diversité de requérants », tel que le souligne Sébastien.

For its part, ACPAT welcomes the involvement of Geneva in a completely different way. What may be observed is a mechanism of certification (Neveu, 2019) by substitution, i.e. an environmentalist discourse that is inaudible in the Chablais but promulgated by a powerful local authority on the other side of the border. Some activists, like Édith and Sébastien, say they are looking forward to “escalating [the issue of the A412 project] to the level of the Swiss Confederation” in the hope of establishing the legitimacy of their arguments. The CSO is therefore exploiting Geneva’s support as part of a strategy of piling up appeals against the French government which, as Sébastien points out, “has no other example […] where there is such a diversity of appellants”.

D’une situation où deux associations se faisaient localement face sur des terrains de jeu distingués, Genève a conduit au resserrement de la lutte pour susciter une controverse dans le proche. Pour Désenclavement, il a fallu ajuster les discours pour défendre la pertinence d’un projet autoroutier à l’échelle locale, registre jusque-là laissé au compte de l’ACPAT. Pour cette dernière, l’écho de Genève donne la possibilité d’un relais par des instances publiques officielles, ce dont elle avait pu manquer jusqu’à présent. En définitive, Genève a incité les acteur∙ice∙s de la mobilisation à se saisir de thématiques similaires avec pour conséquence de durcir les positions concurrentielles sur la « juste » mobilité, au cœur d’un combat pourtant vieux de 25 ans.

From a situation where two CSOs were engaged in local confrontation on separate playing fields, Geneva’s entry into the arena has led to a contraction of the conflict to generate controversy at local level. Désenclavement had to adjust its rhetoric to defend the relevance of a motorway project on a local scale, a scene hitherto left to ACPAT. For its part, the latter has used the fallout from Geneva as an opportunity to have their message taken up by official public bodies, something that may have been lacking until now. In the final analysis, Geneva has encouraged the activists to take up similar issues, with the consequence that competitive positions on “fair” mobility–which are at the heart of a battle that has now lasted 25 years–have hardened.

Promouvoir davantage de justices mobilitaires

Promoting various mobility justice

Dans une synthèse de son travail sur la justice mobilitaire, Mimi Sheller s’interroge sur la nature des ingrédients (matériels, sociaux, idéels) pour « supporter une mobilité plus juste » (Sheller, 2018b). Sans aucun doute, certaines infrastructures de transport, certaines manières de les concevoir, incluent davantage l’ensemble des populations, qu’importe leur genre, leur classe sociale ou leur lieu de résidence. Cependant, l’idée qu’il n’existerait qu’une et une seule mobilité juste, socialement et environnementalement équitable, unanimement célébrée par la société civile et à laquelle les collectivités seraient sommées de répondre, apparaît plus discutable.

In a summary of her work on mobility justice, Mimi Sheller considers the nature of the ingredients (material, social, ideal) needed to “sustain fairer mobility” (Sheller, 2018b). There is no doubt that certain transport infrastructures, certain ways of designing them, are more inclusive of all populations, regardless of gender, social class or place of residence. However, the idea that there is one and only one fair, socially and environmentally equitable form of mobility, unanimously celebrated by civil society and that local authorities are called upon to respond to, seems more debatable.

La mobilisation autour d’un projet d’autoroute dans le Chablais français témoigne d’une situation où des associations locales développent des conceptions concurrentes de la justice mobilitaire, adaptées à leurs ressources d’autochtonie respectives. L’attention portée aux dimensions spatiales de cette contestation permet de mettre en évidence d’inégales tentatives d’imposer un modèle de territoire conforme, que l’inauguration/abandon de l’infrastructure doit venir officialiser. Cette fonction « d’entrepreneur de spatialisation » (Dechézelles et Olive, 2019, p. 23) procède de deux mécanismes interdépendants. D’un côté, les militant·e·s (dé)valorisent l’enclavement, convoquant, pour certain·e·s, les vertus d’une proxim(obil)ité en danger, pour d’autres, les prémices d’un territoire en décroissance. De l’autre, s’affairant à convaincre de l’(in)utilité d’une autoroute dans le proche, elles (dé)légitiment certains déplacements selon leurs destinations, renvoyant à la question du droit à se mouvoir. Ces mécanismes rappellent combien les associations s’investissent par et pour leur espace de vie, qu’il s’agisse de le préserver ou de le développer. Surtout, ils soulignent que la mobilité devient problématique en ce qu’elle dépend et révèle de trajectoires individuelles ou de rapports au territoire, plus que pour être l’objet de la contestation.

The mobilisation around a motorway project in the French Chablais region illustrates a situation where local CSOs develop competing conceptions of mobility justice, corresponding to their respective indigenous resources. Placing the focus on the spatial dimensions of this opposition highlights the uneven attempts to impose a corresponding territorial model, which will become official with the inauguration/abandonment of the infrastructure. This role as “spatialisation contractor” (Dechézelles and Olive, 2019, p. 23) is the product of two interdependent mechanisms. On the one hand, activists (de)value isolation, in some cases invoking the virtues of a proximity under threat and in others the first signs of a territory in decline. On the other hand, in the process of convincing people of the (in)utility of a motorway in the vicinity, they (de)legitimise certain journeys on the grounds of destination, raising the question of the individual right to movement. These mechanisms are a reminder of the extent to which CSOs engage in and on behalf of the space they inhabit, whether for purposes of preservation or development. Above all, they highlight the fact that mobility becomes problematic when it depends on and reveals individual trajectories or relationships with the territory, rather than because it is a target of opposition.

En définitive, les outils de la sociologie des mouvements sociaux et la théorie de la justice mobilitaire gagneraient à de plus amples rapprochements. La variété des premiers ouvre la voie à une conception moins univoque de la seconde, afin d’observer des luttes dans la société civile pour imposer, à légitimités inégales, des valeurs concurrentes de la mobilité. En retour, aborder les mobilisations par la justice mobilitaire jette les bases de résultats originaux, à même d’estomper une opposition entre pro- et anti-automobiles. Dans le présent article, cette rencontre s’effectue à deux niveaux. Sur la récupération partisane du mythe des effets structurants d’abord, pour montrer comment les associations développent et délivrent une expertise profane du territoire pour concurrencer les responsables de l’aménagement de ce dernier. Sur le recours à la notion de controverse dans le proche ensuite, pour souligner l’attente par les militant·e·s d’une certification de bons usages – les leurs – d’un territoire de vie partagé. C’est aussi supposer, une fois les gagnant·e·s déclaré·e·s, la célébration d’une légitimité à habiter le territoire chablaisien plutôt que le sort d’une infrastructure de transport.

Ultimately, the instruments of the sociology of social movements and mobility justice theory would benefit from closer links. The variety of the former opens the way to a less univocal conception of the latter, in which civil society struggles serve to impose–with unequal legitimacies–competing values of mobility. In turn, approaching activist movements from the perspective of mobility justice lays the groundwork for unexpected outcomes that can blur the opposition between pro- and anti-car positions. In this article, this meeting takes place on two levels. Firstly, at the level of partisan exploitation of the myth of structuring effects, to show how CSOs develop and deliver tacit knowledge about the territory that can compete with those responsible for planning it. Next, on the notion of controversy in the local sphere, to highlight the expectation of activists that the right uses–i.e., their own uses–of a shared living space will be certified. It also implies that, once the winners have been declared, they will celebrate the legitimacy of living in the Chablais region rather than the fate of a transport infrastructure.

Pour citer cet article

To quote this article

Gumy Alexis, 2025, « Deux associations face au désenclavement : une lecture concurrentielle de la justice mobilitaire » [“The disenclavement of a region: two civil society organisations with competing approaches to mobility justice ”], Justice spatiale | Spatial Justice, 19 (http://www.jssj.org/article/deux-associations-face-au-desenclavement-une-lecture-concurrentielle-de-la-justice-mobilitaire/).

Gumy Alexis, 2025, « Deux associations face au désenclavement : une lecture concurrentielle de la justice mobilitaire » [“The disenclavement of a region: two civil society organisations with competing approaches to mobility justice ”], Justice spatiale | Spatial Justice, 19 (http://www.jssj.org/article/deux-associations-face-au-desenclavement-une-lecture-concurrentielle-de-la-justice-mobilitaire/).

[3] Ces chiffres et les suivants sont issus de différentes publications de l’INSEE et, pour les mesures de trafic, du dossier de concertation public : INSEE, Haute-Savoie : la plus forte croissance démographique de métropole, paru le 11/01/2019, consulté le 30/05/2022 ; INSEE, Dossier complet, Département de la Haute-Savoie (74), paru 21/02/2022, consulté le 30/05/2022 ; INSEE, Travailleurs frontaliers : six profils de « navetteurs » vers la Suisse, paru le 17/05/2022, consulté le 30/05/2022 ; INSEE, Près de la Suisse, un ménage sur deux perçoit un revenu de source étrangère, paru le 10/02/2022, consulté le 30/05/2022 ; Direction régionale de l’environnement, de l’aménagement et du logement Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes (DREAL), Projet de liaison autoroutière concédée entre Machilly et Thonon-les-Bains, concertation publique, paru en Janvier 2016, consulté le 30/05/2022.

[3] These figures and those that follow are taken from various INSEE publications and, for traffic measurements, from the public consultation file: INSEE, Haute-Savoie: la plus forte croissance démographique de métropole, published 11/01/2019, accessed 30/05/2022; INSEE, Dossier complet, Département de la Haute-Savoie (74), published 21/02/2022, accessed 30/05/2022; INSEE, Travailleurs frontaliers : six profils de “ navetteurs “ vers la Suisse, published 17/05/2022, consulted 30/05/2022; INSEE, Près de la Suisse, un ménage sur deux perçoit un revenu de source étrangère, published 10/02/2022, consulted 30/05/2022; Direction régionale de l’environnement, de l’aménagement et du logement Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes (DREAL), Projet de liaison autoroutière concédée entre Machilly and Thonon-les-Bains, concertation publique, published January 2016, consulted 30/05/2022.

[4] C’était encore vrai au moment de la rédaction de cet article. Le 30/12/2021, le Conseil d’État déboute finalement les opposant∙e∙s, même si tout porte à croire que le dossier est loin d’être clos.

[4] This was still true at the time of writing of this article. On 30/12/2021, the Conseil d’État finally dismissed the opponents’ case, although there is every reason to believe that the matter is far from over.

[5] La plupart de travail d’enquête s’est déroulé pendant la deuxième vague de la COVID-19 (de février 2021 à juillet 2021), une majorité d’entretiens se sont donc fait par visioconférence.

[5] Most of the survey work took place during the second wave of COVID-19 (February 2021 to July 2021), so the majority of interviews were conducted by video.

[6] Cet article s’inscrit dans une recherche doctorale au carrefour de la sociologie urbaine et des sciences de l’ingénierie, s’intéressant aux phénomènes de mobilité dans les espaces frontaliers européens à l’appui majoritaire de méthodes quantitatives (Gumy, 2023).

[6] This article is part of a doctoral research project midway between urban sociology and engineering sciences, focusing on mobility phenomena in European border areas, using mainly quantitative methods (Gumy, 2023).

[7] Si l’ensemble des entités géographiques (en ce qu’elles sont précisément l’objet de la mobilisation) et les noms des associations n’ont pas été anonymisés, tous les noms des enquêté∙e∙s ont été modifiés. Dans la mesure où les deux associations comptent un nombre modéré de membres, la présentation des caractéristiques socio-professionnelles des enquêté∙e∙s reste sommaire afin de respecter leur anonymat.

[7] While all the geographical entities (insofar as they were the actual target of the mobilisation) and the names of the organisations have not been anonymised, all the names of the respondents have been altered. Because both organisations have relatively few members, their socio-economic characteristics have been described cursorily in order to maintain their anonymity.

[9] Au cours de mes entretiens, me présentant comme ingénieur en transports, j’ai souvent été sollicité pour émettre un avis personnel sur le mythe des effets structurants du transport. Il me semble que cela témoigne d’une recherche incessante d’arguments susceptibles de faire pencher la balance d’un côté ou de l’autre de la contestation.