Introduction

Introduction

Bien qu’une large majorité de la population autochtone états-unienne vive aujourd’hui en ville, elle suscite encore bien peu d’intérêt de la part des chercheurs comme des journalistes, des hommes et des femmes politiques ou encore des milieux artistiques, l’opinion commune étant que l’« identité autochtone » se dissout dans la ville. Par ailleurs, les quelques travaux consacrés aux Amérindiens urbains se concentrent le plus souvent sur les questions sociales et identitaires. Cet article propose pour sa part d’analyser les revendications des Autochtones urbains à travers le prisme de la justice spatiale, c’est-à-dire d’utiliser « la dimension spatiale de la justice entre les hommes » comme grille de lecture (Bret, 2015).

Although today the majority of the Indigenous population of the United States lives in cities, it still does not arouse much interest from researchers, journalists and politicians or from artistic circles, the general opinion being that “Indigenous identity” dissolves in the city. In addition, the few works dedicated to urban American Indian most often focus on social and identity issues. This article will analyse the claims of urban Indigenous peoples through the prism of spatial justice, i.e. it will use the spatial dimension of justice between people as a working framework (Bret, 2015).

La question de la justice spatiale concernant les Amérindiens reste taboue aux Etats-Unis, dans la mesure où elle implique de réfléchir sur l'essence même de ce pays et sur la légitimité des structures socio-spatiales en place. En effet, la conquête progressive du territoire américain et son aménagement par les nouveaux venus d’origine européenne ont mis les Amérindiens spatialement à la marge, les confinant dans des réserves[1] à l’écart des villes, le plus souvent dans des zones rurales peu fertiles. L’urbanité, symbole de la modernité et de la civilisation, a dès lors été perçue comme étrangère et incompatible avec l’autochtonie. Les Amérindiens se sont ainsi trouvés hors des lieux de pouvoir de la société états-unienne, marginalisés politiquement, économiquement et socialement.

The issue of spatial justice regarding the American Indians remains taboo in the United States, insofar as it involves thinking about the very essence of the country and the legitimacy of the current socio-spatial structures. Indeed, the progressive conquest of the American territory and its development by the European newcomers, have placed American Indians spatially on the margins, confining them to reserves[1] away from the cities, most often in rural areas with low fertility levels. From then on, urbanity, as the symbol of modernity and civilisation, has been perceived as foreign and incompatible with indigenousness. As a result, American Indians have found themselves outside the places of power of American society, and have been politically, economically as well as socially marginalised.

Cet héritage a marqué durablement les esprits, qui peinent aujourd’hui à envisager que l’on puisse être à la fois amérindien et urbain. Pourtant, aux Etats-Unis, les Amérindiens vivent pour plus de 60% d’entre eux dans des villes (Lobo, Peters, 2001). Ainsi New York, Los Angeles ou encore l’agglomération de San Francisco sont aujourd’hui parmi les villes où vivent le plus d’Amérindiens. Cependant, ces derniers ne forment pas un groupe homogène. Ainsi trouve-t-on à San Francisco des descendants des tribus[2] amérindiennes qui vivaient sur le territoire de la ville avant sa création, mais aussi des Amérindiens qui vivaient tout autour de la Baie et qui ont été progressivement « englobés » dans l’agglomération au cours du XXème siècle, sous l’effet de l’étalement urbain. Mais les Amérindiens les plus nombreux sont ceux qui, notamment dans les années 1950, ont migré en ville depuis d’autres régions sous l’effet d’une politique fédérale les y encourageant, et dont l’objectif était de diluer les identités amérindiennes en ville pour mieux les faire disparaître.

This heritage has had a long-lasting effect on the minds of people who, today, find it hard to imagine that one can be Indigenous and urban at the same time. Yet, in the United States, more than 60% of American Indians live in cities (Lobo, Peters, 2001), New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco being the first three. American Indians however do not form a homogeneous group. In San Francisco, one finds descendants of Indigenous tribes[2] that were living on the land before the city was built, as well as American Indians who used to live around the Bay and who were progressively “included” in the urban area during the 20th century, as a result of urban sprawling. But the largest number of American Indians concerns those who, during the 1950s in particular, migrated towards the city from other regions after they were encouraged to do so by a federal policy that aimed at diluting Indigenous identities in town, with a view to ensuring their disappearance.

En raison de cette hétérogénéité culturelle des Amérindiens urbains, les injustices spatiales sont perçues différemment selon les groupes, qui ont ainsi chacun des revendications spécifiques. Pour les Amérindiens ayant migré à San Francisco pendant la seconde moitié du XXème siècle, le but est de mettre fin aux discriminations dont ils sont l’objet et d’obtenir un accès aux ressources de la ville, tout en défendant leur droit à exprimer pleinement leur(s) identité(s) dans l’espace urbain. Remédier à l’injustice spatiale passe ici par la mise en place d’« une justice distributive » inscrite dans un « cadre territorial » permettant le « respect des identités individuelles et collectives » (Bret, 2015). En revanche, pour les Amérindiens autochtones, au sens de « ceux qui sont d’ici » (c’est-à-dire qui vivent encore aujourd’hui sur le territoire de leurs ancêtres), l’injustice spatiale est plus directement liée à la colonisation qui s’est traduite par l’appropriation illégitime d’un territoire qu’il s’agit de récupérer, au moins en partie. La question de l’autochtonie urbaine s’exprime ainsi en termes de justice spatiale, comprise différemment selon les acteurs et leur histoire propre.

Due to the cultural heterogeneity of the urban American Indians, spatial injustice was perceived differently according to groups, each having its own specific claim as a result. For the American Indians who migrated to San Francisco during the second half of the 20th century, the objective is to end the discrimination to which they are subjected and to access the resources of the city, while defending their right to fully express their identities in the urban space. Solving spatial injustice requires the establishment of a “distributive justice” written in a territorial framework leading to the “respect of individual and collective identities” (Bret, 2015). On the other hand, for autochthonous American Indians, i.e. for “those who are from here” and who still live today on the land of their ancestors, spatial injustice is more directly linked to colonisation, which was translated into the illegitimate appropriation of a territory that needs to be recovered, partly at least. As such, the issue of urban autochthony is expressed in terms of spatial justice, which is understood differently according to the actors and their own history.

L’analyse géographique me semble essentielle pour (re)penser la place des Amérindiens en ville, comme le montrent, par exemple, les travaux de géographes canadiens auprès des acteurs de la ville et des communautés amérindiennes urbaines. Leurs études révèlent l’existence d’identités amérindiennes urbaines en mutation, tout en mettant en évidence les injustices spatiales subies par ces groupes, en matière d’accès au logement et à l’éducation notamment (Peters, Andersen, 2013). Aux Etats-Unis, l’étude des Amérindiens urbains est souvent portée par des chercheurs amérindiens au service de leur communauté ou par des anthropologues engagés politiquement qui ont le souci de l’utilité sociale de leurs travaux et qui se tournent, en l’occurrence, vers le soutien de causes amérindiennes[3]. Si l’apport de ces recherches est indéniable, leur visée pratique – soutenir les actions de revendication des groupes étudiés – limite la possibilité de conduire une réflexion plus large sur l’articulation entre droit à la ville et justice spatiale.

A geographical analysis seems essential to (re)think the place of American Indians in the city, as shown for example by the works of Canadian geographers concerning city actors and urban Indigenous communities. Their studies reveal the existence of changing urban Indigenous identities, while emphasizing the spatial injustice to which these groups have been subjected, particularly as far as access to housing and education are concerned (Peters, Andersen, 2013). In the United States, the study of urban American Indians is often conducted by Indigenous researchers at the service of their community, or by politically committed anthropologists concerned about the social usefulness of their work and who, to be specific, turn towards supporting Indigenous causes[3]. While the input of this type of research is undeniable, its practical aim – supporting the protests of the groups being studied – limits the possibility of conducting a wider discussion on the link between the right to the city and spatial justice.

Cet article se propose de prendre en charge cette réflexion, à partir d’une lecture géographique du rapport des Autochtones à la ville dans la baie de San Francisco. Je m’interrogerai sur ce que les différents acteurs entendent lorsqu’ils parlent de « justice » et mettrai en évidence les rivalités de pouvoir autour de l’appropriation du territoire de la ville. La baie de San Francisco constitue en effet un lieu privilégié pour l’étude des nouvelles réalités urbaines autochtones. Ses universités et ses villes ont été au cœur de la mobilisation en faveur de la reconnaissance des droits civiques (civil rights)[4] dans les années 1960, et c'est aussi là que la renaissance politique amérindienne s'est fait connaître avec les premières actions d'envergure des activistes autochtones, notamment l'occupation de l'île d'Alcatraz en 1969. Aujourd'hui, la baie de San Francisco compte l’une des populations amérindiennes les plus importantes et hétérogènes du pays (48 469 personnes selon les données de l'US Census Bureau, 2010). Elle est le théâtre de multiples mouvements de revendications territoriales portés par différents groupes ohlone (Amérindiens originaires de la Baie) qui demandent à être reconnus comme autant de nations amérindiennes. Les enjeux sont importants, car la reconnaissance fédérale ouvre la possibilité de revendiquer une parcelle de terre en ville et d'y ouvrir un casino[5].

This article intends to deal with this discussion, by examining the relationship Indigenous people have with the city in the San Francisco Bay area, from a geographic perspective. We will examine what the different actors understand when they speak of “justice”, and show the existence of power rivalries where urban land appropriation is concerned. The Bay area constitutes a privileged place for the study of new Indigenous urban realities. The universities and towns of the Bay have been central in promoting the recognition of civil rights[4] in the 1960s. The Bay is also where the rebirth of Indigenous policies took place, with the first large-scale interventions of Indigenous activists, and the occupation of Alcatraz Island in 1969 in particular. Today, the San Francisco Bay area has one of the largest and most heterogeneous Indigenous population in the country (48 469 people according to the US Census Bureau, 2010). It is the scene of many movements of territorial claims presented by various Ohlone groups (American Indians originating from the Bay) who are asking to be recognised as one of many Indigenous nations. In this light, stakes are high since Federal recognition opens the possibility to claim a plot of land in town, and open a casino[5] on it.

Il s’agira donc dans cet article de s’interroger sur ces luttes autochtones et ce qu’elles révèlent du rapport des Amérindiens urbains au territoire. Après un rapide point méthodologique, mon analyse sera développée en trois temps. La présentation des populations autochtones de l’aire urbaine de San Francisco mettra l’accent sur leur hétérogénéité, ce qui permettra d’exposer et expliquer ensuite les différentes stratégies portées par des acteurs autochtones en quête de justice spatiale. Enfin, l’analyse du cas spécifique d’une tribu originaire de l’aire urbaine sera l’occasion de mettre en lumière un nouveau rapport au territoire urbain et une expression de l’autochtonie intégrée dans une économie des jeux d’argent florissante.

In this article, we will examine the struggles of Indigenous peoples and what they reveal about the relationship urban American Indians have with their land. After making a rapid description of the methodology, our analysis will be developed into three sections. In the presentation of the Indigenous populations of the San Francisco metropolitan area, we will emphasise their heterogeneousness, then set out and explain the different strategies assumed by Indigenous actors in search of spatial justice. Finally, analysing the specific case of a tribe originating from the urban Bay area will be an opportunity to bring to light a new relationship with an urbanized territory, as well as an expression of indigenousness integrated into a flourishing gaming economy.

Précisions méthodologiques

Methodological Precisions

Cet article tire sa matière d’une thèse de doctorat conduite au début des années 2010 (Leclère, 2014). Si mon analyse s’appuie pour partie sur des données quantitatives (issues notamment des recensements états-uniens), ma réflexion s’est principalement nourrie des apports d’une enquête qualitative conduite in situ d’octobre 2011 à août 2012[6] et qui m’a permis d’identifier et comprendre les stratégies et les représentations des acteurs. Le travail de terrain a fait la part belle aux entretiens semi-directifs. L’une des principales difficultés était de mettre à jour les réseaux et les interrelations entre les acteurs, et ce alors que les populations amérindiennes de la Baie ne sont pas regroupées dans un même quartier mais, au contraire, dispersées dans toute l’agglomération. Aux entretiens formels, il faut ajouter les discussions informelles improvisées au gré des rencontres, par exemple lors d’événements ou de manifestations culturelles et/ou politiques. Si la communauté panindienne[7] s’est montrée très ouverte à cette recherche, il en a été différemment des tribus locales et, le plus souvent, des acteurs politiques. « What’s happening in Indian Country is Indian business » (« Ce qui se passe en Territoire indien ne regarde que les Indiens »), m’ont dit plusieurs de mes interlocuteurs. Cette méfiance s’explique par les enjeux économiques et politiques des revendications territoriales des tribus dans les aires urbaines, en raison de la floraison depuis plus d’une décennie de ce que l’on nomme les « casinos indiens »[8] sur les parcelles de terrains attribuées à telle ou telle tribu à la suite de longues démarches juridiques. La multiplication de ces établissements est un sujet très polémique, une bonne partie de l’opinion américaine voyant d’un mauvais œil l’implantation de telles activités à proximité de leurs lieux de résidence. Les tribus sont donc très prudentes en matière de communication avec l’extérieur, soucieuses qu’elles sont de projeter une image positive d’elles-mêmes. Elles ont conscience que la recherche universitaire peut aussi bien servir la cause des tribus amérindiennes, notamment en matière de revendications territoriales, que celle des lobbys opposés à la création de « casinos indiens ».

This article draws its material from a doctoral thesis conducted at the beginning of the 2010s (Leclère, 2014). While our analysis relies partly on quantitative data (obtained from American censuses in particular), our discussion was fostered mainly by inputs from a qualitative survey, conducted in situ from October 2011 to August 2012[6], and which led us to identify and understand actors’ strategies and representations. The field work gave more than their due to semi-directive interviews. One of the main difficulties was to bring networks and interrelations between actors up to date, since the Indigenous populations of the Bay do not live all together in the same suburb but rather, are scattered throughout the urban area. In addition to formal interviews, there were also improvised informal discussions as encounters happened, for example during cultural and/or political events or demonstrations. While the Pan-Indian community[7] was very open to my research, things were different with local tribes and, more often, with political actors. Several interlocutors told me that “What’s happening in Indian Country is Indian business”. The lack of trust can be explained by the economic and political stakes of the land claims of the tribes in urban areas, due to the flourishing – for over a decade – of what are known as “Indian casinos”[8] on the lands allocated to one tribe or another, after long legal processes. The multiplication of gambling places is a very controversial subject, in that many Americans see the establishment of casinos near their own homes as a problem. As a result, tribes are very careful with the way they communicate with the outside, anxious as they are to project a positive image. They know that academic research can serve “the cause” of tribes, particularly as regards land claims, just as it can serve that of lobbies opposed to the creation of “Indian casinos”.

Les peuples autochtones de la baie de San Francisco : des communautés invisibles ?

The Indigenous Peoples of the San Francisco Bay: Invisible Communities?

Dans l’imaginaire des Européens comme des Nord-américains, les espaces associés aux Amérindiens sont les réserves, loin des villes (Comat, 2012). Dans l’inconscient collectif, la ville est l’espace du colon, de la civilisation : l’autochtone n’y a donc pas sa place, à moins d’en adopter les codes et de renoncer à son identité spécifique. Ces représentations sont confortées par le manque de visibilité des populations autochtones en ville, alors même qu’à l’échelle des Etats-Unis, les Amérindiens sont majoritairement urbains aujourd’hui.

In the imagination of Europeans and North Americans in particular, the spaces associated with American Indians are the reserves, far from cities (Comat, 2012). In the collective unconscious, the city is the space of the settler and civilisation: therefore, Indigenous peoples have no place there, unless they adopt city codes and renounce their own identities. These representations are reinforced by the fact that Indigenous populations are not very visible in town, even though today the majority of American Indians live in urban areas country-wide.

Cette absence de visibilité est l’effet d’un rapport démographique largement défavorable aux Amérindiens en ville. La présence autochtone se retrouve ainsi diluée dans la société multiculturelle américaine, à l’instar des Amérindiens de la baie de San Francisco souvent qualifiés d'« invisibles » par les chercheurs (Lobo, 2002). En effet, bien que la population amérindienne de la baie soit l’une des plus importantes du pays, elle représente moins de 1% de la population de l'aire urbaine, soit quelques dizaines de milliers de personnes (US Census Bureau, 2010), principalement des Amérindiens venus d’ailleurs et qui se sont installés là au cours de la seconde moitié du XXème siècle. Les descendants des tribus originaires de la Baie et y vivant encore forment quant à eux un groupe très restreint qui ne dépasse pas le millier de personnes.

This lack of visibility results from a demographic relationship which is mainly unfavourable to American Indians in town. The presence of Indigenous peoples becomes diluted in multicultural American society, just like that of the American Indians of the San Francisco Bay who are often described by researchers as being “invisible” (Lobo, 2002). Indeed, although the Indigenous population of the Bay is one of the largest in the country, it still represents less than 1% of the total urban population, i.e. a few dozens of thousands of people (US Census Bureau, 2010), mainly American Indians from other places who settled there during the second half of the 20th century. As to the descendants of tribes originating from the Bay and still living there, they form a very small group of no more than a few thousand people.

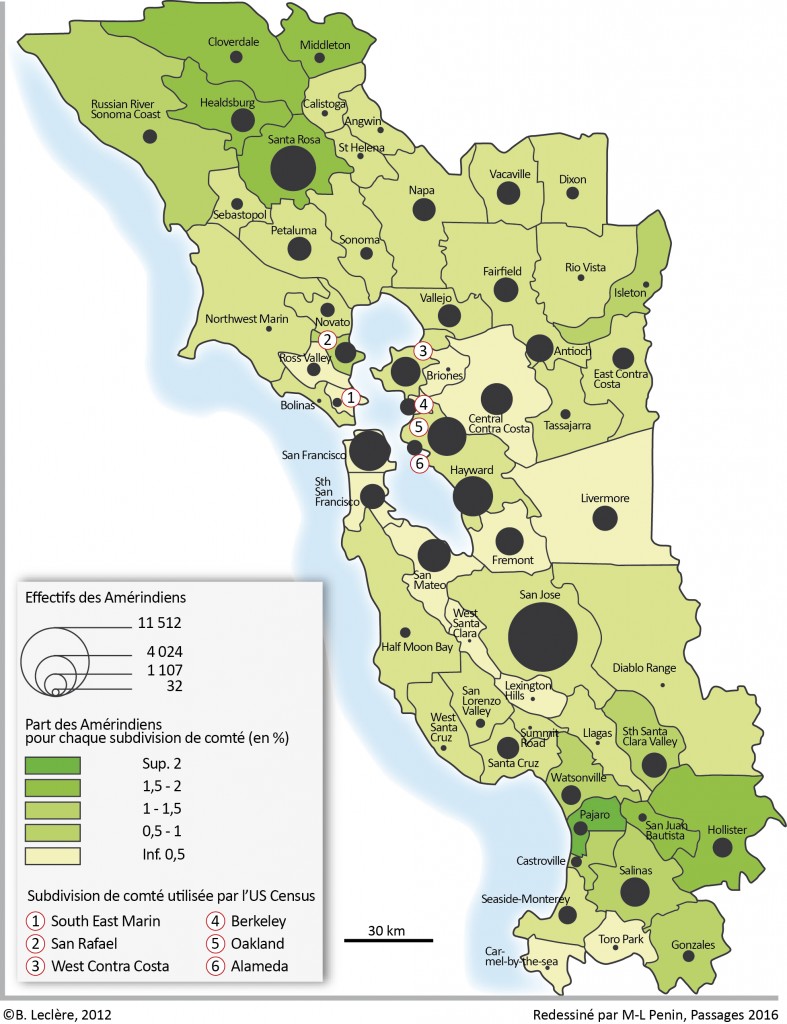

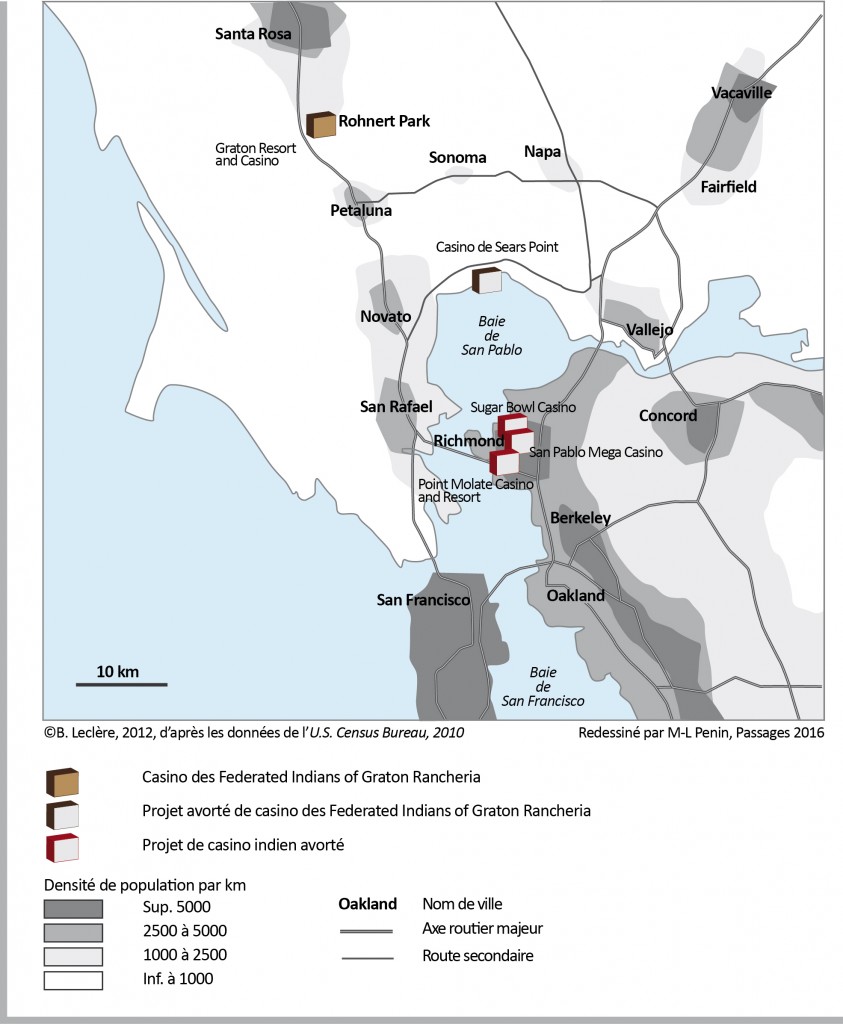

L’invisibilité résulte aussi d’une répartition spatiale particulière au sein de l’aire urbaine. On observe sur la carte ci-dessous (carte 1) un tropisme fort des Amérindiens vers les principaux pôles urbains de la Baie : San Jose, San Francisco, Oakland et Berkeley. Mais dans ces villes, à la différence des minorités afro-américaines ou asiatiques, les Amérindiens sont dispersés et ne se concentrent pas dans des quartiers spécifiques (Carocci, 2007). C’est là le résultat des politiques fédérales des années 1950 qui favorisaient l’installation des Amérindiens en ville. Il s’agissait d’éviter les regroupements afin d’accélérer l’assimilation à la société majoritaire et la disparition des cultures. En dépit de cette stratégie, ces Amérindiens néo-urbains sont cependant parvenus à se structurer dès les années 1960 et à exister en tant que communauté amérindienne unie, par-delà des appartenances tribales.

Invisibility also results from specific spatial distribution within the urban area. We can see on the map below (Map 1) a high tropism of American Indians towards the main urban centres of the Bay: San Jose, San Francisco, Oakland and Berkeley. However, in these towns, unlike Afro-American or Asian minorities, American Indians are scattered all over and are not concentrated in specific suburbs (Carocci, 2007). This is due to the federal policies of the 1950s that favoured the settlement of American Indians in town. The idea was to avoid gatherings in order to speed up assimilation to the majority society as well as the disappearance of cultures. Despite this strategy, neo-urban American Indians managed to organise themselves in the 1960s and exist as a united Indigenous community, beyond tribal memberships.

Carte 1 : Les Amérindiens de l’aire urbaine franciscaine : une population « invisible » ? (US Census Bureau, 2010)

Map 1: The American Indians of the San Francisco Urban Area: An Invisible Population? (US Census Bureau, 2010)

Constitution d'une indianité urbaine dans l’aire urbaine de la baie de San Francisco

Constituting Urban Indianness in the Urban Area of the San Francisco Bay

Les migrations amérindiennes et le poids des politiques fédérales d’assimilation

Indigenous Migrations and the Weight of Federal Assimilation Policies

Les Amérindiens commencent à migrer en ville dans la première moitié du XXème siècle. Les causes de ces mobilités sont toujours multiples et propres aux histoires personnelles des acteurs. Néanmoins, d’une façon générale, les raisons économiques sont déterminantes (Fixico, 2000). Si quelques familles amérindiennes s’installent dans l’aire urbaine franciscaine dès le début du XXème siècle pour trouver du travail, c’est surtout au lendemain de la Seconde Guerre mondiale que le mouvement s’intensifie, conduisant à la constitution d’une communauté panindienne - c'est-à-dire constituée d'Amérindiens membres de diverses tribus et originaires de différentes régions des Etats-Unis. Dans les années 1950, le gouvernement fédéral conduit une politique d’assimilation à l’égard des Amérindiens qui se traduit par la mise en place des relocation programs. Alors que la majorité d’entre eux vit alors dans des réserves, il s’agit de promouvoir leur intégration dans le creuset américain, en les incitant à s’installer en ville. L'Etat fédéral s'engage à les aider dans leur installation, par un accès préférentiel à l'embauche, une mise à disposition de logements et une aide financière (Fixico, 2000). Les conditions de vie très difficiles dans les réserves et l’intense campagne de promotion des relocation programs jouent un rôle majeur dans l’urbanisation des Amérindiens dans les années 1950. Peu armés pour affronter le choc de la vie en ville, ces néo-urbains se sentent noyés au milieu des autres cultures, des autres communautés. C'est dans ce contexte que beaucoup de jeunes, qui n’ont pas (ou peu) connu la vie dans les réserves, réagissent en se réclamant de l'« indianité », une identité générique qui dépasse les appartenances à telle ou telle tribu qui ne font plus sens pour ces générations urbaines.

The American Indians began to migrate in town during the first half of the 20th century. Although the reasons for this were varied and specific to individual histories, generally, economic reasons represented a determining factor (Fixico, 2000). While a few Indigenous families settled in the urban area of San Francisco, as early as the beginning of the 20th century, to look for work, it was mainly just after WWII that the movement intensified, leading to the constitution of a Pan-Indian community – i.e. made up of American Indians from various tribes and originating from different regions of the United States. In the 1950s, the Federal Government conducted an assimilation policy that concerned American Indians and that was translated into the establishment of relocation programmes. While the majority of American Indians lived in reserves, the idea was to promote their integration into the American melting pot, by encouraging them to settle in town. The Federal State undertook to help them settle, by giving them priority as far as employment, housing and financial assistance were concerned (Fixico, 2000). The very difficult living conditions in the reserves and the intense promotional campaign of the relocation programmes played a major role in urbanising American Indians in the 1950s. Little prepared as they were to face the shock of living in town, these neo-city dwellers felt themselves drowning in the middle of the other cultures and communities. It was in this context that many youth, who did not know life in the reserves or little of it, reacted by claiming their “Indianness”, a generic identity that went beyond membership to one tribe or another, which no longer made sense to these urban generations.

Cette jeunesse amérindienne prend conscience des injustices subies (en matière d’accès à la santé, à la justice, à l’éducation, au logement…) et demande à avoir les mêmes droits que les autres citadins (Fixico, 2000). Cette quête de justice socio-spatiale n’est pas spécifique aux Amérindiens puisque d’autres groupes, tels que les Afro-américains, sont victimes de discriminations dans le San Francisco des années 1950 et s’organisent également pour venir en aide à leur communauté. Aussi cet engagement a-t-il eu un effet pervers. Parce qu’à l’instar d’autres communautés, les populations autochtones dénonçaient les injustices socio-spatiales dont elles étaient les victimes, elles ont été considérées comme une minorité parmi d’autres à intégrer dans la ville, et non pas comme des nations différentes ayant un rapport spécifique au territoire, ancré dans une histoire longue.

Youths became aware of the injustice suffered by their people (as regards access to health, justice, education and housing among others), and asked to be given the same rights as other city dwellers (Fixico, 2000). This quest for socio-spatial justice was not specific to the American Indians. Other groups, such as the African-Americans, were also the victims of discrimination in the San Francisco of the 1950s, and also decided to organise themselves to help their own community. But this commitment had a pernicious effect. Because the Indigenous populations, like other communities, denounced the socio-spatial injustice victimising them, they ended up being considered as a minority among others to be integrated into the city, and not as different nations with a specific relationship with the land that was rooted in a long history.

Une communauté panindienne qui demande un droit à la ville

A Pan-Indian Community Asking for a Right to the City

Les luttes amérindiennes prennent progressivement leur place dans le paysage urbain de la Baie à partir du milieu des années 1950, avec l’ouverture de locaux en ville dévolus à l'aide sociale aux populations autochtones. Des associations panindiennes comme l'Intertribal Friendship House, créée en 1955 à Oakland, permettent aux Amérindiens urbains de se réunir et de célébrer leurs identités (Lobo, 2002). Pour les jeunes Amérindiens, il s’agit alors d’afficher sa fierté d’être amérindien et pleinement citadin. Cette défense de l'indianité passe souvent par l'activisme qui est perçu comme le moyen de faire vivre la culture amérindienne et de la rendre visible aux yeux de l'opinion publique américaine. A Oakland, les jeunes Amérindiens observent les actions d'autres communautés comme celle des Afro-américains. La création du Black Panther Party[9] en 1966 et la mise en place des survival programs vont donner des idées aux activistes amérindiens, qui sont influencés par ce modèle (Ogbar, 2005). Ainsi tentent-ils de se regrouper dans des associations et à travers des programmes d'aide sociale construits sur le modèle des Black Panthers. Des réseaux se mettent en place grâce aux nœuds que représentent les maisons où sont situés ces associations et programmes d'aides. Ainsi, des Indian survival schools voient le jour dans la Baie et l'American Indian Child Resource Center est créé en 1972 à Oakland, non loin de l'Intertribal Friendship House. A San Francisco, c'est le quartier de Mission District (image 1) qui concentre le plus de services aux populations amérindiennes avec le Native American Health Center, ou encore l'International Indian Treaty Council. L'offre d'aide sociale s'y concentre car dans les années 1960 et 1970 le prix du foncier y est moins élevé qu'ailleurs. Mission District est par ailleurs un quartier caractérisé par une certaine centralité : il est bien relié au réseau de transports en commun.

Pro-Indigenous action progressively took its place in the urban landscape of the Bay, from the middle of the 1950s, with the opening in town of premises dedicated to social welfare for Indigenous peoples. Pan-Indian associations such as the Intertribal Friendship House, created in 1955 in Oakland, gave urban American Indians an opportunity to meet and celebrate their identities (Lobo, 2002). For young American Indians, one had to display Indigenous pride and plain city membership. Defending Indianness often went through activism, which was perceived as a means to support Indigenous culture and make it visible to the American public. In Oakland, young American Indians observed the interventions of other communities such as that of the African-Americans. The creation of the Black Panther Party[9], in 1966, and the establishment of survival programmes gave Indigenous activists ideas, the latter being subsequently influenced by this model (Ogbar, 2005). They tried to unite through associations and welfare programmes built on the Black Panthers model. Networks were established thanks to the nodes or houses hosting these associations and welfare programmes. As such, Indian survival schools saw the light in the Bay and the American Indian Child Resource Center was created in 1972, in Oakland, not far from the Intertribal Friendship House. In San Francisco, it was in the Mission District (Image 1) where the majority of services were offered to Indigenous populations, with the Native American Health Center or, still, the International Indian Treaty Council. Social welfare was concentred there because during the 1960s and the 1970s, property prices were cheaper than anywhere else. Moreover, Mission District was fairly central and was well served by public transport.

Image 1 : Huttes de sudation devant l’entrée du centre de désintoxication amérindien de San Francisco, Mission District (© B. Leclère, 2012)

Image 1: Sweat lodges in front of the entrance of the American Indian detoxification centre of San Francisco, in Mission District (© B. Leclère, 2012)

Une communauté panindienne marquée par l’essoufflement des luttes du passé

A Pan-Indian Community Marked by the Fact That Past Struggles Have Run Out of Steam

En raison de leur ancienneté, ces lieux d'entre-aide communautaire sont aujourd'hui intégrés dans le paysage urbain. Ils sont toujours fréquentés par la communauté panindienne locale, notamment par les migrants amérindiens d'Amérique latine. Ces derniers sont de plus en plus présents lors d’événements culturels ou lorsque des consultations médicales sont offertes par le Native American Health Center. Il s’agit principalement de migrants venant du Mexique ou d’Amérique centrale, souvent en situation précaire et pour lesquels les centres d’aide dédiés aux Amérindiens représentent une ressource parmi d’autres dans le quartier de Mission. Pour les activistes amérindiens de la Baie (comme ceux de l’American Indian Movement[10]), ces néo-migrants sont essentiels pour donner un nouveau souffle à l’activisme panindien, qui semble perdre en intensité depuis trois décennies en raison de l’assimilation progressive des Amérindiens arrivés dans le cadre des relocation programs. Les injustices dont sont victimes les migrants d’Amérique latine deviennent ainsi le nouveau cheval de bataille de la communauté amérindienne au sens large, ces luttes étant aussi l’occasion de continuer à affirmer la présence des Amérindiens en ville[11]. Comme précisé précédemment, le manque de visibilité dans la ville est un défi majeur pour les Amérindiens. En intégrant progressivement une partie des migrants d’Amérique latine, la communauté panindienne se renforce démographiquement. Cependant, cette intégration contribue par ailleurs à renforcer les représentations et imaginaires déjà existants auprès de l’opinion publique, à savoir que les Amérindiens viennent de territoires qui se trouvent loin des villes et que leur(s) culture(s) ne sont que peu compatibles avec l’urbanité. L’image 2 ci-dessous en est une illustration.

Today, due to their age, these community places are integrated into the urban landscape. They are always visited by the local Pan-Indian community and by Indigenous immigrants from Latin America in particular. The latter increasingly attend organised cultural events or medical consultations offered by the Native American Health Center. These immigrants come mainly from Mexico or Central America, and are often in a precarious situation. For them, the help centres dedicated to American Indians represent one resource among others in the Mission District. For the Indigenous activists of the Bay (like those of the American Indian Movement[10]), these new immigrants are essential in giving a new lease of life to Pan-Indian activism, which seems to have been loosing intensity for the past three decades, due to the progressive assimilation of American Indians who came as part of a relocation programme. As such, the injustice suffered by immigrants from Latin America has become the new main concern of the Indigenous community in general, these fights being also an occasion to continue to assert the presence of American Indians in town[11]. As specified previously, the lack of visibility in town is a major issue for the American Indians. By progressively integrating part of the Latin American immigrants, the Pan-Indian community becomes demographically reinforced. However, this integration can also contribute to reinforcing the existing representations and opinions of the public, i.e. that the American Indians come from territories situated far away from cities and that their cultures are little compatible with urbanity. The photograph below illustrates this point (Image 2).

Image 2 : Danseurs aztèques, cérémonie du Lever du Soleil sur l’île d’Alcatraz, le 10 octobre 2011 (© B. Leclère, 2011)

Image 2: Aztec dancers during the Sunrise ceremony, Alcatraz Island, on 10 October 2011 (© B. Leclère, 2011)

Le cliché a été pris le 10 octobre 2011, à l’occasion de la cérémonie du Lever du Soleil à Alcatraz qui vient commémorer l’occupation de l’île d’Alcatraz en 1969 par un collectif d’Amérindiens[12]. Au premier plan, on peut voir des danseurs aztèques avec leurs coiffes impressionnantes, qui correspondent bien à l’image d’Épinal attachée aux Amérindiens du Mexique. En arrière-plan, on distingue un tipi, qui était utilisé par certaines tribus amérindiennes comme les Lakota des Grandes Plaines. Le cinéma américain a contribué à diffuser cette image stéréotypée d’Amérindiens génériques vivant tous sous des tipis et chassant le bison ; une représentation qui fait fi de la grande diversité des tribus vivant aux Etats-Unis, et ailleurs dans le monde (Mankiller, West, 2007). Ainsi, ce type de mise en scène de l’indianité renforce les représentations dominantes des Amérindiens aux Etats-Unis, à savoir qu’ils viennent forcément d’ailleurs (ici, les Grandes Plaines, le Mexique) et qu’ils ne peuvent que ponctuellement et de façon folklorique exprimer leur identité en ville (pendant les rassemblements comme celui d’Alcatraz). Lors de manifestations culturelles ou lors d’actions collectives, les Amérindiens donnent ainsi à voir ce qu’on attend d’eux pour se donner une plus grande visibilité médiatique. Pour eux, il s’agit évidemment aussi de réaffirmer l’identité ou les identités amérindiennes en ville. Cependant, lors de la cérémonie du Lever du Soleil, le 10 octobre 2011, malgré la forte mobilisation des Amérindiens de la Baie, la couverture médiatique de l’événement a été quasi-nulle. Les photographes présents étaient ceux des associations amérindiennes et autochtones et aucune télévision n’a été dépêchée sur place. Alcatraz étant devenu un lieu de pratiques collectives amérindiennes ritualisées et régulières (la cérémonie a lieu tous les ans), il semblerait que les médias non autochtones ne s’y intéressent plus guère.

This photo was taken on the 10th of October 2011, on the occasion of the Sunrise ceremony in Alcatraz, which commemorates the occupation of the Island in 1969 by a collective of American Indians[12]. In the foreground, we can see Aztec dancers with their impressive headdresses, who correspond to the idealised images of American Indians from Mexico. In the background, we can see a tipi, which was used by certain Indigenous tribes such as the Lakota of the Great Plains. American cinema contributed to spreading this stereotyped image of generic American Indians living inside tipis and hunting bisons, a representation which flouts the great diversity of tribes living in the United States, and elsewhere in the world (Mankiller, West, 2007). This type of staging of Indianness reinforces the dominant representations of American Indians in the United States, which is that they must come from elsewhere (the Great Plains and Mexico in this case) and that they can only express their identity in town in a specific and folkloric manner (during gatherings like this one in Alcatraz). During cultural events or collective actions, American Indians show what is expected of them for greater visibility and media coverage. For them, it is also of course about reasserting American Indian identity or identities in town. However, during the Sunrise ceremony on the 10th of October 2011, despite the high mobilisation of American Indians from the Bay, the media coverage of the event was almost non-existent. The photographers present were those of the American Indian and Indigenous associations, and no television crew had been sent on site. Where Alcatraz has become the site of ritualised and regular practices by Indigenous collectives (the ceremony takes place every year), it seems that the non-Indigenous media no longer takes an interest in it.

Dans l’aire urbaine de la baie de San Francisco, les luttes amérindiennes pour plus de justice spatiale semblent donc être devenues moins importantes que par le passé. Il est vrai que pour la communauté panindienne, et pour une grande partie de l’opinion publique de la Baie, les injustices socio-spatiales sont moins criantes qu’autrefois, et les Amérindiens peuvent désormais exprimer leur indianité en ville lors d’événements culturels ponctuels. Cependant, cette expression ne semble possible que dans la mesure où les groupes autochtones apparaissent comme des minorités et non comme des nations ayant un lien territorial avec la ville. Car si le droit à la ville de la communauté panindienne de San Francisco apparaît aujourd’hui comme moins problématique que par le passé, il en va différemment pour les quelques centaines d’Amérindiens descendants des tribus amérindiennes originaires de la Baie qui n’ont, jusqu’à aujourd’hui, pas obtenu de reconnaissance fédérale. Pour eux, l’espace de la ville continue d’être un territoire contrôlé par le groupe dominant.

In the urban area of the San Francisco Bay, Indigenous struggles for more spatial justice seem to have become less important than in the past. It is true that for the Pan-Indian community, and for a large portion of the public living in the Bay, socio-spatial injustice is less blatant than before, and the American Indians can from now on express their Indianness in town during specific cultural events. However, this expression only seems possible insofar as Indigenous groups appear as minorities and not as nations having a territorial link with the city. While the right to the city of the Pan-Indian community of San Francisco appears today as less problematic than in the past, things are different for the few hundreds of American Indians descending from tribes originating from the Bay and who, to date, have not obtained federal recognition. For them, the city continues to be a space controlled by the dominant group.

Des peuples en quête de reconnaissance

People in Search of Recognition

Les Amérindiens de la Baie ont-ils disparu ?

Have the American Indians from the Bay Disappeared?

L’histoire officielle veut que les Amérindiens de la Baie aient été décimés par les colons ou assimilés par les missions catholiques du temps des Espagnols. Au début du XXème siècle, l'anthropologue de l'université de Berkeley, Alfred Kroeber, qui a longtemps fait autorité sur la question, a ainsi écrit que les Ohlone, qui habitaient la Baie de San Francisco à l’arrivée des Européens, sont une tribu désormais « éteinte » (« extinct ») (Kroeber, 2012 [1925] ; Ramirez, 2007). Cette idée d'extinction des Ohlone en tant que tribu, validée officiellement au niveau fédéral, est largement répandue dans l’opinion publique. Pourtant, depuis les années 1980, on assiste à leur renaissance.

Official history says that the American Indians from the Bay were decimated by the settlers or assimilated by the catholic missions during the Spanish period. At the beginning of the 20th century, University of Berkeley anthropologist Alfred Kroeber, who for a long time was an authority on the subject, wrote that the Ohlone, who lived in the Bay of San Francisco when the Europeans arrived, are a tribe which is from now on “extinct” (Kroeber, 2012 [1925]; Ramirez, 2007). This idea that the Ohlone are extinct as a tribe, and which was officially validated at federal level, is widely spread in the public mind. Yet, we have been witnessing their rebirth since the 1980s.

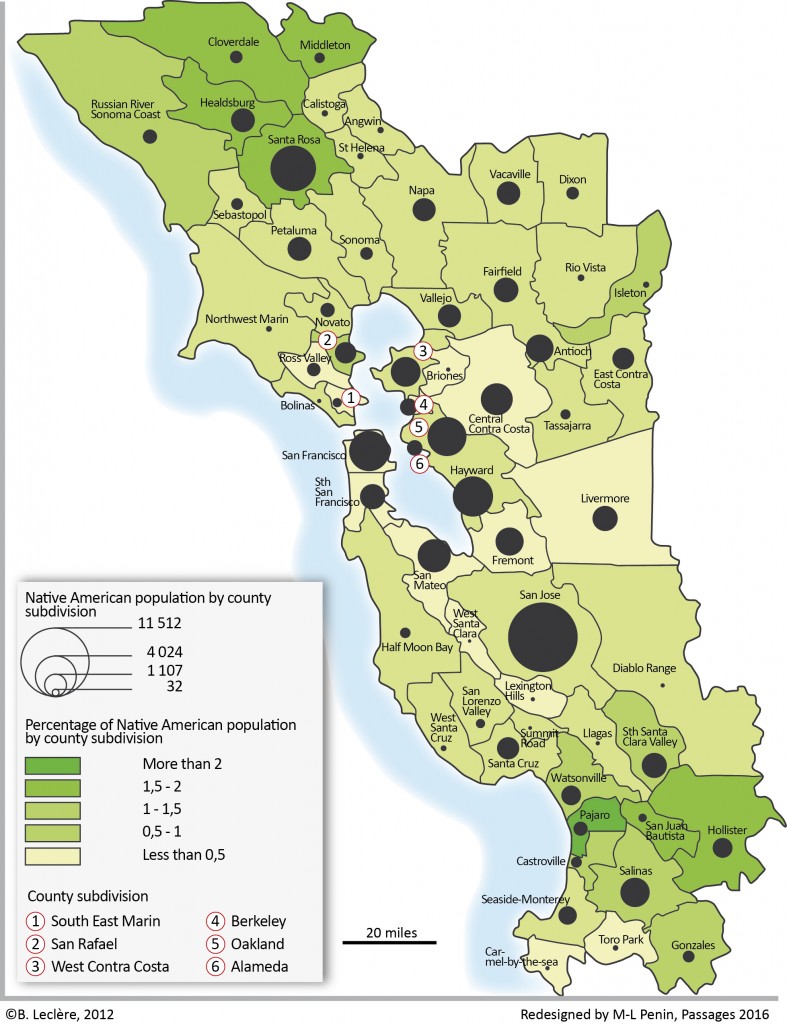

Actuellement, sept groupes tribaux demandent à être reconnus par l'Etat fédéral (carte 2). Il s'agit de l'Amah Band of Ohlone/Costanoan Indians (devenue l'Amah Mutsun Tribal Band et l'Amah Tribal Band), des Costanoan Band of Carmel Mission Indians, des Indian Canyon Band of Costanoan/Mutsun Indians, de la Muwekma Indian Tribe, de la Costanoan Ohlone Rumsen-Mutsun Tribe et de l'Ohlone/Costanoan-Esselen Nation (Pritzker, 1999). La plupart des tribus ohlone comptent entre 400 et 500 membres et se situent toutes au sud de la baie de San Francisco. La tribu des Costanoan Band of Carmel Mission Indians est un cas particulier, car elle se situe en dehors de l’aire linguistique ohlone et la plupart de ses membres résident à Pomona, à l'est de Los Angeles. De plus, ce groupe comprend 2000 membres, soit beaucoup plus que les autres tribus ohlone (chaque tribu met en place ses propres critères d'acceptation de nouveaux membres dans la tribu, ces règles étant inscrites dans ce que les tribus appellent leurs constitutions).

Currently, seven tribal groups have asked to be recognised by the Federal State (Map 2). These are the Amah Band of Ohlone/Costanoan Indians (who became the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band and the Amah Tribal Band), the Costanoan Band of Carmel Mission Indians, the Indian Canyon Band of Costanoan/Mutsun Indians, the Muwekma Indian Tribe, the Costanoan Ohlone Rumsen-Mutsun Tribe and the Ohlone/Costanoan-Esselen Nation (Pritzker, 1999). Most Ohlone tribes have between 400 and 500 members and are all situated in the South of the Bay of San Francisco. The tribe of the Costanoan Band of Carmel Mission Indians is a special case, in that it is situated outside the Ohlone linguistic area, and most of its members reside in Pomona, East of Los Angeles. Moreover, this group has 2 000 members, which is much more than the other Ohlone tribes (each tribe establishes its own criteria for accepting new members, these rules being inscribed in what the tribes call their constitutions).

Carte 2 : Groupes tribaux ohlone, situés au sud de la baie de San Francisco

Map 2: Ohlone tribal groups situated in the South of the Bay of San Francisco

Chacune de ces tribus non reconnues à l’échelon fédéral développe une stratégie qui lui est propre pour obtenir sa reconnaissance. Plus qu’une fin en soi, la reconnaissance est un moyen, car in fine, l’objectif est d’ouvrir un casino dans ou à proximité de l’aire urbaine de San Francisco, ouverture permise sur les terres sous souveraineté amérindienne grâce aux traités historiques signés avec le gouvernement fédéral. Ces casinos sont aujourd’hui perçus par les tribus comme l’activité la plus à même de soutenir leur développement économique, et d’assurer ainsi leur futur, y compris sur le plan culturel.

Each one of these tribes which are not recognised at federal level are developing a specific strategy to obtain recognition. More than an end in itself, recognition is a means, for in the end the objective is to open a casino in or near the urban area of San Francisco, which would be possible on the lands under American Indian sovereignty, thanks to the historical treaties signed with the Federal Government. Today these casinos are perceived by the tribes as the most likely activity to sustain their economic development and as such ensure their future, including culturally.

Obtenir la reconnaissance fédérale s’avère toutefois un processus long et coûteux. En effet, les groupes tribaux doivent rassembler des documents reconnus par les cours de justice prouvant leur présence continue en tant que tribu sur le territoire de la Baie. Les tribus font pour cela appel à des anthropologues et des ethno-historiens qui travaillent en réponse à une commande spécifique. Ainsi l'anthropologue Les Field a travaillé pour la Muwekma Ohlone Indian Tribe dès la fin des années 1980 pour soutenir la tribu dans sa première demande de reconnaissance fédérale. Dans ses travaux, Field critique ou nuance (selon les cas) les études des anthropologues mobilisées antérieurement par le gouvernement fédéral pour justifier son refus de reconnaître certaines tribus californiennes, et insiste sur l’obligation pour Washington de « réparer » l’injustice faite ainsi à ces tribus. Field, assume sa position de chercheur appointé par une tribu pour atteindre des objectifs précis et la justifie au nom de la nécessité, pour l'anthropologie, de faire acte de repentance pour le rôle qu’elle a joué dans le processus de non reconnaissance fédérale de nombre de tribus amérindiennes au cours du XXème siècle. En choisissant de travailler pour une tribu, l'anthropologue devient ainsi un activiste (Field, 1999).

Obtaining federal recognition turns out to be a long and costly process. Indeed, tribal groups must gather documents that are recognised by the courts and can prove their continued presence, as a tribe, in the Bay area. To this end, the tribes call on anthropologists and ethno-historians who work in response to a specific request. Anthropologist Les Field worked for the Muwekma Ohlone Indian Tribe, as early as the end of the 1980s, to assist with the tribe’s very first request for federal recognition. In his research work, Field criticised or qualified (as the case may be) the studies of anthropologists formerly mobilised by the Federal Government, to justify its refusal to recognise certain Californian tribes, and insisted on the obligation Washington had to “right” the wrongs suffered by these tribes. Field assumed his position of reasearcher appointed by a tribe in reaching specific objectives, and justified this position in the name of the necessity anthropology had to repent for the role this science played in many tribes not being recognised at federal level during the 20th century. By chosing to work for a tribe, an anthropologist as such becomes an activist (Field, 1999).

Si les coûts inhérents à la constitution d’un dossier en vue d’une reconnaissance fédérale sont importants pour les tribus, c’est aussi parce qu’à la rémunération de l'équipe de recherche il faut ajouter le financement de lobbys dont le rôle est d’influencer les décisions prises à Washington. A titre d'exemple, de 2010 à 2013, la Muwekma Ohlone Indian Tribe aurait versé 60 000 $ au lobbyiste Joseph Findaro[13], qui défend les intérêts de différentes tribus amérindiennes à Washington depuis plus d'une décennie. Les tribus ohlone qui cherchent à obtenir leur reconnaissance fédérale ont donc besoin de créanciers sur lesquels s'appuyer. Selon différentes sources[14], la Muwekma Ohlone Indian Tribe a été financée pendant les deux décennies de sa procédure par un riche investisseur de Floride, Alan Ginsburg, qui s'intéresse aux tribus susceptibles d'ouvrir des casinos dans les principales aires urbaines du pays. Jusqu’à présent, aucune tribu ohlone de l’aire urbaine franciscaine n’a pu obtenir une reconnaissance fédérale, et donc la propriété d’un territoire en ville sur lequel exercer sa souveraineté et ouvrir un casino. Les tribus ohlone demandent que justice soit faite au nom du préjudice subi par les premiers habitants de la Baie, soit leurs aïeux. Elles considèrent la reconnaissance officielle de leur statut de tribus par le gouvernement fédéral comme une réparation. Cependant, une telle réparation, si elle vise à plus de justice sociale, ne mettrait pas fin à l’injustice spatiale subie, à savoir le fait que les tribus amérindiennes ont été dépossédées de leurs terres. C’est pourquoi les tribus ohlone réclament également une compensation, à savoir un territoire en ville sur lequel exercer leur souveraineté. Or, cela est jugé inacceptable par une partie de l’opinion publique et certains élus tels que la sénatrice de Californie Dianne Feinstein, qui peinent à imaginer des tribus souveraines à l’intérieur de l’aire urbaine. Ainsi, pour s’imposer, les tribus doivent choisir habilement les lieux où elles souhaitent s’implanter. La justice spatiale devient alors possible pour les groupes tribaux qui investissent le plus dans la communication et dans les lobbys. A proximité de San Francisco, seule la tribu des Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria a réussi à ouvrir un casino. Ce cas particulier mérite donc que l’on s’y attarde.

While the costs inherent to compiling a dossier for federal recognition are considerable for the tribes, they are also due to the remuneration of the research team and that of financing lobbies tasked with influencing the decisions taken in Washington. For example, from 2010 to 2013, the Muwekma Ohlone Indian Tribe supposedly paid USD 60 000 to lobbyist Joseph Findaro[13], who has been defending the interests of various tribes in Washington for over a decade already. Ohlone tribes seeking to obtain federal recognition need financial backers they can rely on. According to different sources[14], the Muwekma Ohlone Indian Tribe was financed, for the two decades of the procedure, by wealthy Florida investor Alan Ginsburg, who was interested in tribes likely to open casinos in the main urban areas of the country. To date, none of the Ohlone tribes of the urban area of San Francisco managed to obtain federal recognition or ownership of a piece of land in the city on which they could exercise their sovereignty and open a casino. The Ohlone tribes ask that justice be done in the name of the prejudice suffered by the first inhabitants of the Bay, i.e. their ancestors. They consider the official recognition of their tribal status by the Federal Government as reparation. However, while such reparation aims at more social justice, it would not put an end to the spatial injustice suffered, i.e. the fact that tribes have been dispossessed of their lands. That is why the Ohlone tribes also ask for compensation, i.e. a piece of land within the city on which they can exercise their sovereignty. Yet, this is deemed unacceptable by some members of the public and certain elected representatives, such as Californian Senator Dianne Feinstein, who find it hard to imagine tribes exercising their sovereignty inside the urban area. As such, in order to assert themselves, tribes must be skilful in choosing the sites where they wish to settle. Spatial justice becomes possible for tribal groups investing the most in communication and lobbies. Close to San Francisco, only the tribe of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria succeeded in opening a casino. This special case deserves a closer look.

Les Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria : une tribu amérindienne qui a réussi à s'imposer au nord de la Baie

The Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria: An American Indian Tribe that Succeeded in Asserting Itself North of the Bay

La tribu est reconnue à l'échelle fédérale depuis 2000 grâce au travail de son chef, Greg Sarris, un universitaire originaire de la région de Santa Rosa, au nord de la Baie. Il suit des études universitaires à UCLA et à Stanford dans les années 1980, avant de devenir professeur de littérature[16]. C'est pendant ses études qu'il décide d’en savoir plus sur ses origines amérindiennes. Cette donnée peut sembler anecdotique mais est à prendre en compte dans la mesure où nous sommes ici dans le cas d’une construction tribale contemporaine. En effet, dans les années 1980, Greg Sarris découvre le passé amérindien de ses ancêtres. Cette recherche identitaire personnelle va rapidement se transformer en une volonté de créer une tribu au début des années 1990, au moment où les premiers casinos amérindiens fleurissent dans l'Etat. Greg Sarris entame alors, au nom de la tribu, des démarches à Washington afin d'obtenir la reconnaissance fédérale, perdue en 1958. Seules trois solutions existent : entamer une procédure via la Cour fédérale, obtenir un executive order du Président ou faire passer une loi au Congrès[17]. C'est cette dernière voie qui finit par aboutir en 2000. Le contexte politique est alors favorable car le gouvernement Clinton souhaite régler différents litiges avec les tribus amérindiennes avant la fin du deuxième mandat présidentiel, ces dernières étant de plus en plus perçues comme des alliés politiques en vue des élections. Cependant, bien que reconnus, les Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria n'ont alors pas de territoire sur lequel exercer leur souveraineté.

This tribe has been recognised at federal level since 2000, thanks to tribe Chief Greg Sarris, an academic originating from the region of Santa Rosa, North of the Bay. He studied at UCLA and Stanford in the 1980s, before becoming a lecturer in literature[16]. It was during his studies that he decided to know more about his American Indian origins. Although this piece of information might seem anecdotal, it needs to be taken into account, insofar as we are dealing here with a case of contemporary tribal construction. Indeed, in the 1980s, Greg Sarris discovered that his ancestors were American Indians. This personal identity search was rapidly transformed into a desire to create a tribe at the beginning of the 1990s, at the time when the first American Indian casinos flourished in the State. Greg Sarris then began, in the name of the tribe, procedures in Washington with a view to obtaining federal recognition, which had been lost in 1958. Only three solutions exist in seeking recognition: initiating a procedure via the Federal Court, obtaining an executive order from the President or getting a law to be passed by Congress[17]. It was the last option that was used and came to a successful end in 2000. At the time, the political context was favourable in that the Clinton administration wanted to settle various disputes with the tribes, before the end of the second presidential mandate, because tribes were increasingly perceived as political allies in view of the elections. However, although they were recognised, the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria did not have a territory on which to exercise their sovereignty.

Pour ouvrir un casino, la tribu doit donc entreprendre des démarches à deux niveaux : d’abord, à l'échelle fédérale, où il s'agit de constituer un dossier rassemblant suffisamment de preuves scientifiques concernant les liens ancestraux au territoire revendiqué, puis à l'échelle locale, où il faut faire accepter le projet aux riverains et aux autorités locales.

To open a casino, the tribe must undertake procedures at two levels: first, at the federal level, where it must compile a dossier gathering enough scientific proof concerning its ancestral links to the land claimed, and secondly at the local level, where the project needs to be accepted by local residents and authorities.

De la reconnaissance fédérale à l'obtention d'une trust land à Rohnert Park : une stratégie tribale efficace

From Federal Recognition to Trust Land in Rohnert Park: An Efficient Tribal Strategy

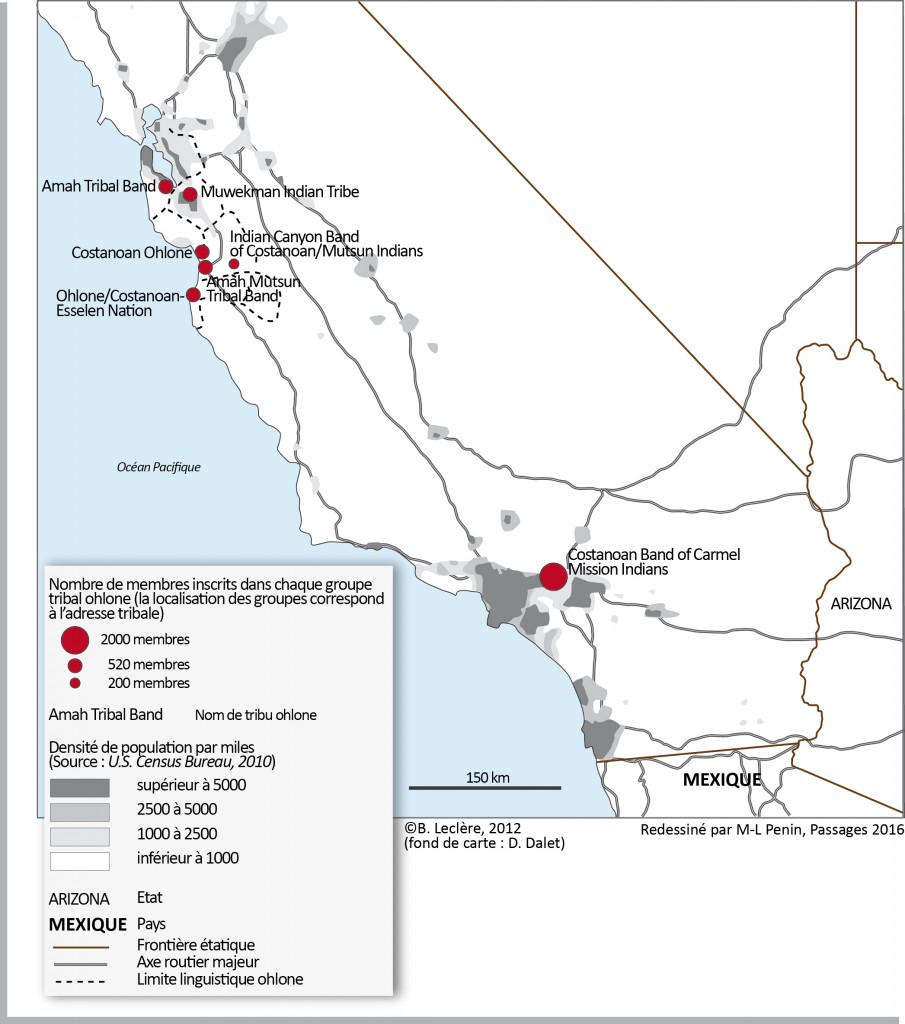

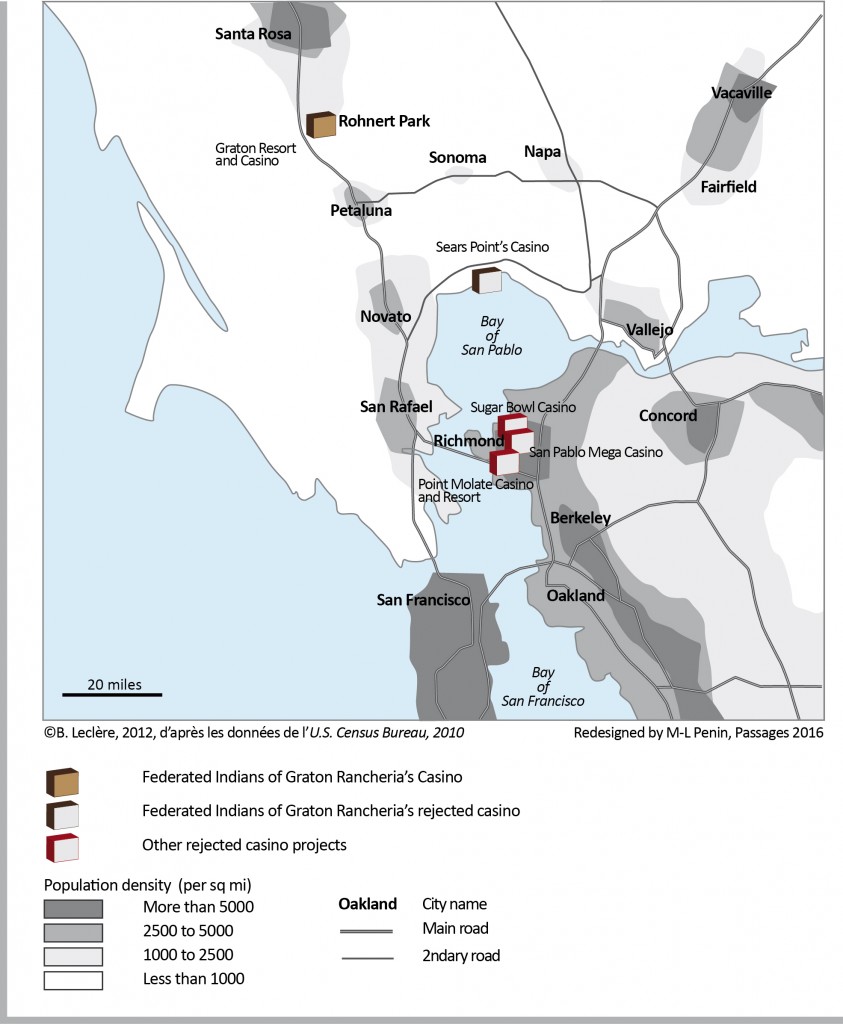

Le site de Sears Point est d'abord envisagé pour faire l'objet d'une demande de trust land au gouvernement fédéral (il s’agit de terres confiées par Washington à certaines tribus, notamment celles qui n’ont plus de terres, et sur lesquelles elles peuvent exercer leur souveraineté). Ce projet est vite remis en cause par l'opposition de la sénatrice Feinstein. Aussi la tribu entame-t-elle alors des démarches pour obtenir une trust land au sud de l'agglomération de Santa Rosa, dans la ville de Rohnert Park (carte 3).

The site of Sears Point was first considered when applying for a trust land to the Federal Government (these are lands entrusted by Washington to certain tribes, especially those with no more land, and on which the latter can exercise their sovereignty). This project was quickly questioned by opposing Senator Dianne Feinstein. The tribe then initiated procedures to obtain a trust land south of the Santa Rosa urban area, in the town of Rohnert Park (Map 3).

Carte 3 : Les Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria : une implantation réussie au nord de la baie de San Francisco

Map 3: The Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria: A Successful Settlement North of the Bay of San Francisco

En octobre 2010, le Department of Interior décide d'attribuer une centaine d'hectares à la tribu en périphérie de Rohnert Park. Cette décision est le résultat de plusieurs années de travail pour rassembler le plus grand nombre de preuves scientifiques de leurs liens à la terre. Des archives familiales de descendants de tribus ont été exhumées et des recherches généalogiques ont été menées pour reconstituer la tribu. Au début des années 1990, au moment où la tribu souhaite obtenir la reconnaissance fédérale, elle compte 152 membres[18]. Aujourd'hui, elle en compte plus de 1000, qui sont les descendants de deux groupes tribaux distincts - la tribu Coast Miwok et les Southern Pomo Indians – qui vivaient au nord de la Baie. Cet ensemble composite répond à des impératifs plus économiques que culturels, dans la mesure où c'est l'obtention d'une trust land qui est visée. En effet, l'objectif est de créer une tribu qui puisse, grâce à la grande diversité de ses membres, rassembler suffisamment de preuves de liens ancestraux au territoire revendiqué. De même, on assiste à une professionnalisation des membres de la tribu dans le domaine de la recherche puisque certains d’entre eux entreprennent des études en anthropologie et en archéologie. C’est grâce à ce travail, et au lobbying effectué à Washington, que la tribu parvient à constituer un dossier très complet qui lui permet d'obtenir en 2010 une trust land à Rohnert Park.

In October 2010, the Department of Interior decided to allocate around one hundred hectares to the tribe on the outskirt of Rohnert Park. This decision was the result of several years of work to gather as much scientific proof as possible, concerning their link to the land. The family archives of tribal descendants were dug up and genealogical research works were conducted to reconstitute the tribe. At the begining of the 1990s, at the time when the tribe wanted to obtain federal recognition, it had 152 members[18]. Today, it has more than 1 000 members who actually descend from two distinct tribal groups – the Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo Indian tribes – that used to live north of the Bay. This composite whole was more in response to an economic necessity than a cultural one, insofar as the objective was to obtain a trust land. Indeed, the objective was to create a tribe that, thanks to the great diversity of its members, could gather enough evidence of ancestral links to the land being claimed. As a result, some tribal members decided to focus on the vocational side of the research, and began studies in anthropology and archaeology. It was thanks to this research and to the lobbying carried out in Washington that the tribe managed to put together a very complete dossier that led, in 2010, to obtaining a trust land in Rohnert Park.

Les Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria face au « phénomène nimby »

The Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria Confronted with the Nimby Phenomenon

Un collectif, Stop the casino 101, formé par des habitants de Rohnert Park, s'est opposé au projet d’ouverture d’un casino en remettant en cause la légitimité de la tribu et de ses membres, et en demandant l’annulation de la reconnaissance fédérale des Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria. La « compensation territoriale » accordée à la tribu apparaît aux yeux des habitants de Rohnert Park comme une injustice. Ils protestent contre les éventuelles nuisances qu’un casino pourrait provoquer dans leur quartier (hausse de la criminalité, augmentation du trafic routier). Ce collectif, dont on peut estimer qu’il relève du phénomène « nimby » désormais bien connu, n’est cependant pas parvenu à obtenir le retrait du projet (Subra, 2007). Le premier problème rencontré par les opposants au casino de Rohnert Park a été le peu d'intérêt porté à cette petite ville par les habitants de l'aire urbaine de San Francisco. Bien que proche géographiquement de celle-ci, elle en est très éloignée dans les représentations des Franciscains. Aussi, la création d'un casino à Rohnert Park n'est pas perçue par ceux-ci comme une menace.

An association called Stop the casino 101 created by residents of Rohnert Park, opposed the casino project by questioning the legitimacy of the tribe and its members, and by requesting the cancellation of the federal recognition of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria. In the eyes of Rohnert Park residents, the land compensation granted to the tribe was an injustice. They protested against the potential nuisance a casino could cause in their suburb (increase in crime and road traffic). However, this association, deemed to result from the by now well-known “nimby” phenomenon, did not manage to obtain the project’s withdrawal (Subra, 2007). The first problem encountered by the opponents of the casino of Rohnert Park, was the little interest shown by the residents of the urban area of San Francisco to this little town. Although they are geographically close to each other, Rohnert Park is very distant in the representations of the San Francisco residents who, as such, did not view the creation of a casino in Rohnert Park as a threat.

Pour convaincre davantage de personnes, les opposants au projet ont donc dû montrer que leur revendication n'était pas seulement locale mais qu’elle touchait en réalité l’ensemble du pays. Le collectif a alors changé de stratégie en utilisant la législation en place afin de ralentir les projets de la tribu. Pour construire un casino, la tribu doit entrer en négociation avec l'Etat où elle souhaite s'implanter et fournir un plan détaillé du projet ainsi qu’une étude de son impact environnemental. Avec le soutien d'écologistes et d'hommes politiques locaux, les membres de Stop the casino 101 ont ainsi attaqué en justice la tribu, l'accusant de n'avoir pas suffisamment pris en compte les données environnementales du site. Les arguments avancés sont, somme toute, assez classiques dans les conflits d'aménagement urbain : le casino provoquerait un afflux massif de voitures, source de pollution ; le complexe hôtelier épuiserait les ressources locales en eau ; et, enfin, la création du casino provoquerait la disparition de la salamandre tigrée, une espèce protégée vivant sur le site[19]. Conscients de ce pouvoir de nuisance du collectif Stop the casino 101, les Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria ont alors pris grand soin de construire des partenariats forts à l'échelle locale pour limiter l'opposition. Dès 2010, la tribu a entamé une stratégie de greenwashing, notamment en orientant quelques-uns de ses jeunes membres vers des études universitaires directement utiles à la tribu. Il s’agissait de produire des recherches mettant en avant les liens entre écologie et culture tribale ancestrale. Simultanément, la tribu a adopté une posture de défense de l'environnement à travers des partenariats, comme par exemple avec le California State Parks. Elle a également donné 500 000 dollars pour la revalorisation du parc régional de Tolay Lake, au sud de Rohnert Park. Enfin, à cette stratégie s'est ajouté le souci d'être intégrée localement via des dons aux services d'utilité publique du comté et de la ville. Ainsi, en juin 2009, la tribu a donné 500 000 dollars aux pompiers et policiers de la ville de Rohnert Park, montrant à la communauté locale son désir de maintenir un niveau de sécurité élevé dans la ville. Grâce à cette stratégie, la tribu a pu signer des accords avec les responsables politiques de la ville et du comté. Des négociations avec le gouverneur Jerry Brown ont pu commencer en 2011, en vue de l’ouverture d’un casino à Rohnert Park. Enfin, en mars 2012, les accords entre la tribu des Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria et l'Etat de Californie ont été finalisés, permettant ainsi à la tribu d'entamer le début de la construction du casino.

With a view to convincing more people, the opponents of the project had to show that their claim was not only local, but that in fact it affected the entire country. The association then changed its tactic by using the legislation in place to slow down the tribe’s project. To build a casino, the tribe had to enter into negotiation with the State where it wished to settle, and supply a detailed plan of the project as well as an environmental impact study. With the support of local ecologists and politicians, the members of Stop the casino 101 ended up suing the tribe, accusing it of not having sufficiently taken the site’s environmental data into account. The arguments put forward were, on the whole, fairly classic in urban development conflicts: the casino would cause a massive flow of cars, which are a source of pollution; the hotel complex would deplete local water resources; and finally, the creation of a casino would cause the disappearanceof the tiger salamander, a protected species living on the site of the project[19]. Aware of the power association Stop the casino 101 could have, the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria then took great care to build strong partnerships locally, in order to limit the opposition. As early as 2010, the tribe began a greenwashing strategy, by orienting a few of its young members towards university studies that would benefit the tribe directly. The idea was to conduct research that could create a link between ecology and ancestral tribal culture. Simultaneously, the tribe adopted a stand in defense of the environment through partnerships, as with for example the California State Parks. It also donated USD 500 000 for restoring the prestige of the regional park of Tolay Lake, south of Rohnert Park. Finally, in addition to this strategy, the tribe was also concerned with being integrated locally via donations to the public services of the county and the town. Thus, in June 2009, the tribe gave USD 500 000 to the firestation and police station of the town of Rohnert Park, showing the local community its desire to maintain a high level of safety and security in town. Thanks to this strategy, the tribe was in a position to sign agreements with the town and county’s political leaders. It then became possible to initiate negotiations with Governor Jerry Brown in 2011, with a view to opening a casino in Rohnert Park. Finally, in March 2012, the agreements between the tribe of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria and the State of California were finalised, giving the tribe the green light to begin with the construction of the casino.

Pour mener à bien ses projets aux échelles fédérales et locales, la tribu a dû dépenser plusieurs millions de dollars en lobbying, en recherches scientifiques et en dons. Il faut ajouter à cela l'argent nécessaire à la construction du casino, de la salle de concert et de l’hôtel. La tribu a fait appel à un investisseur privé, Station Casinos, une entreprise du Nevada qui possède déjà plusieurs casinos à Las Vegas. En novembre 2013, le Graton Resort and Casino a ouvert ses portes, mettant un terme aux attaques de ses détracteurs. Ce succès, inédit à l'échelle de la Baie, attire la convoitise de nombreuses personnes. Les Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria ont reçu de multiples demandes d'affiliation à la tribu depuis 2013, lesquelles ont presque toutes été refusées. Car tout membre supplémentaire aurait un impact économique négatif pour les membres actuels de la tribu. En effet, une partie des bénéfices du casino est répartie entre les membres de la tribu ; plus le nombre de ces membres est limité, plus les bénéfices individuels pour chacun d’entre eux sont importants. Aussi la tribu a-t-elle adopté, dès 2008 (après avoir obtenu une trust land), des modifications dans sa constitution afin de limiter les possibilités d'entrée dans la tribu. En outre, pour éviter les dérives à l'intérieur de la tribu, les membres actuels ne peuvent pas perdre leur affiliation tribale et ne sont pas soumis à des vérifications rétroactives de leur affiliation.

In order to carry its projects at federal and local levels through to a successful conclusion, the tribe had to spend several millions of dollars in lobbying, in scientific research and in donations, in addition to the money required to build the casino, the concert hall and the hotel. The tribe called on private investor Station Casinos, a Nevada-based company that already owned several casinos in Las Vegas. In November 2013, the Graton Resort and Casino opened its doors, putting an end to the attacks of its detractors. This success, never seen before in the Bay area, has been the object of many people’s desires. In this regard, the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria have received many requests for tribal affiliation since 2013, which have all practically been refused. Any additional member would have a negative economic impact on the current members of the tribe. Indeed, where part of the benefits of the casino is distributed among the members of the tribe, the more limited this number is, the greater the benefits for each individual. In this regard, as early as 2008, after obtaining a trust land, the tribe adopted modifications in its constitution with a view to limiting tribe membership. In addition, to avoid abuse within the tribe, current members cannot loose their tribal affiliation and are not subject to retroactive verifications of their affiliation.

L’analyse du modèle économico-politique développé par certaines tribus amérindiennes, à l’instar des Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, permet de mettre en lumière une redéfinition des rapports de force entre acteurs, notamment entre Autochtones et non-Autochtones, et l'importance prise par le concept de souveraineté dans ces relations. Les tribus jouent ainsi de leurs spécificités pour obtenir des avantages, dont la possibilité de développer l’industrie du jeu. Cet exemple de quête de justice spatiale effectuée par la tribu des Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria soulève cependant des interrogations sur les processus identitaires en cours. Elle suggère, entre autres, que l’exercice de la souveraineté sur les terres réappropriées passe aussi par l’assimilation des valeurs et pratiques de la société dominante. En effet, en adoptant des logiques entrepreneuriales, les tribus s'intègrent pleinement au reste de la société américaine et tentent de réaliser leur propre American Dream.

An analysis of the politico-economic model developed by certain tribes, like the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, brings to light a redefinition of power relations between actors, particularly between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, as well as the significance taken on by the concept of sovereignty in these relations. Tribes make use of their specificities to obtain advantages, including the possibility of developing the games industry. Nonetheless, this example of search for spatial justice as carried out by the tribe of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, raises questions on the current identity processes. It suggests, among other things, that exercising one’s sovereignty on re-appropriated lands also means assimilating the values and practices of the dominant society. Indeed, by adopting entrepreneurial logics, the tribes become fully integrated into the rest of American society, and try to achieve their own American Dream.

Conclusion

Conclusion

La recherche sur les luttes des peuples autochtones met souvent l’accent sur la dimension juridique des conflits avec en toile de fond l’idée d’une appropriation des outils juridiques par les représentants d’organisations ou de communautés autochtones. On étudie assez peu l’espace vécu et l’espace perçu comme autant de manières de vivre son identité autochtone et de s’approprier l’espace.

Studies conducted on the struggles of Indigenous peoples often emphasise the legal dimension of the conflicts with, in the background, the idea of legal tools being appropriated by representatives of Indigenous organisations or communities. Few studies look at the experienced and perceived spaces as many ways of living one’s Indigenous identity and appropriating space.

Pour les Amérindiens appartenant à la « communauté panindienne », vivre son indianité en ville prend des formes multiples et renouvelées. Si les actions collectives médiatiques sont moins fréquentes que dans les années 1980, la lutte de défense de l’indianité trouve aujourd’hui de nouveaux supports avec de nouvelles générations qui revendiquent pleinement leur urbanité amérindienne. Les musiques urbaines ou les peintures murales deviennent autant de moyens d’expression et parfois de marqueurs spatiaux de l’identité amérindienne. La ville peut alors être vécue et perçue comme une « urban rez », c’est-à-dire une réserve urbaine permettant ainsi de sortir des stéréotypes selon lesquels les Amérindiens ne peuvent vivre qu’en dehors des villes pour maintenir la culture de leurs ancêtres (Carocci, 2007). Au contraire, les identités et les cultures amérindiennes trouvent en ville un second souffle en se mêlant aux pratiques urbaines.

For American Indians belonging to the Pan-Indian community, living one’s Indianness in town takes on many and renewed forms. While collective media actions are less frequent than in the 1980s, fighting for Indianness today means new media usage, with the new generations claiming their American Indian urbanness fully. Urban music or murals become as many means of expression and sometimes spatial markers of American Indian identity. The city can then be experienced and perceived as an “urban rez”, i.e. an urban reserve that makes it possible to get away from stereotypes, according to which American Indians can only live outside cities to maintain their ancestors’ culture (Carocci, 2007). On the contrary, American Indian identities and cultures find in town new life by mixing with urban practices.

C’est ainsi que, dans l’agglomération de San Francisco, la jeunesse amérindienne restructure les réseaux traditionnels par l’internet et les réseaux sociaux. Cette appropriation du cyberespace est d’autant plus forte que la baie de San Francisco est l’un des premiers territoires au monde où se diffusent les innovations technologiques et les nouvelles pratiques de l’ère du numérique. Internet apparait comme un outil particulièrement adapté à la réticularité des pratiques amérindiennes. Il est ainsi possible de renouer des liens avec les territoires d’origine quittés lors des relocations programs des années 1960 mais aussi de se mobiliser davantage en mettant en lien des Amérindiens de villes différentes qui partagent des expériences similaires et qui souhaitent continuer la lutte. L’exemple du mouvement Decolonize à l’automne 2011, en marge du mouvement Occupy[20], semble illustrer ce phénomène. Pour les collectifs d’Amérindiens qui se sont formés à Oakland ou à Vancouver, il s’agissait surtout de dénoncer les rapports de force issus de la colonisation et de déconstruire les schémas de pensée occidentaux. Si Decolonize s’est essoufflé à l’instar du mouvement Occupy au cours de l’année 2012, ces nouvelles dynamiques suggèrent que les communautés panindiennes des villes nord-américaines continueront à revendiquer leur droit à la ville.