Profondément marquées par le modèle ségrégationniste d’apartheid, les villes d’Afrique du Sud constituent des cas d’école pour penser les injustices spatiales (Soja, 2010 ; Chapman, 2015). Malgré les efforts déployés depuis l’avènement de la démocratie en 1994 pour enrayer la fragmentation raciale, les pouvoirs publics ne sont guère parvenus à faire disparaître le « fantôme de l’apartheid » (Pieterse, 2006). Les politiques publiques favorables au marché immobilier (Miraftab, 2007 ; Didier et al., 2009), l’augmentation du prix de l’immobilier et les entraves à la redistribution foncière ont exacerbé les inégalités sociales et spatiales (Pieterse, 2002 ; Lemanski, 2007). Woodstock, quartier péricentral de la ville du Cap, est un espace disputé. Sujet à un processus de gentrification, Woodstock concentre les tensions et les intérêts divergents entre les pouvoirs publics, les entreprises privées, les habitants issus des classes moyennes et aisées et ceux des classes populaires. En 2016, une partie des résidents expulsés ou menacés d’expulsion se regroupent au sein de l’organisation Reclaim the City (RTC) et occupent l’ancien hôpital de Woodstock.

Deeply marked by the apartheid model of segregation, South African cities are textbook examples of spatial injustice (Soja, 2010; Chapman, 2015). Despite the efforts made since the advent of democracy in 1994 to curb racial fragmentation, the public authorities have had little success in eradicating the “ghost of apartheid” (Pieterse, 2006). Public policies favourable to the real estate market (Miraftab, 2007; Didier et al., 2009), rising property prices and barriers to land redistribution have exacerbated social and spatial inequalities (Pieterse, 2002; Lemanski, 2007). Woodstock, a district on the outskirts of Cape Town, is a disputed area. Subject to a process of gentrification, Woodstock is a focal point for tensions and divergent interests between public authorities, private companies, middle-class and affluent residents and their working-class counterparts. In 2016, some of the residents who had been evicted or threatened with eviction formed the Reclaim the City (RTC) organisation and occupied the former Woodstock hospital.

Cette contribution s’intéresse au répertoire d’action territorial de RTC, entendu comme l’ensemble des moyens d’action déployés sur un ou plusieurs espaces pour en contester l’appropriation (Tilly et Tarrow, 2015). Le territoire, caractérisé en tant que portion d’espace délimitée sur laquelle s’exerce une autorité, constitue alors un enjeu de lutte à partir duquel il est possible de remettre en question la légitimité de ce pouvoir.

This contribution focuses on RTC’s repertoire of territorial action, understood as the set of forms of action deployed in one or more spaces to oppose their appropriation (Tilly and Tarrow, 2015). Territory, characterised as a delimited portion of space over which an authority is exercised, then comes to constitute a locus of struggle from which the legitimacy of this power can be challenged.

Il s’agit donc d’explorer à la fois l’appropriation du quartier par le mouvement social et la façon dont ce dernier réalise le passage de revendications particulières, centrées sur l’occupation, à des revendications plus générales portant sur le droit à rester dans le quartier et à une remise en cause du modèle de développement urbain postapartheid, troublant ainsi la configuration spatiale et raciale ségréguée du Cap. Comment le mouvement RTC utilise-t-il l’espace urbain pour contester son appropriation par les promoteurs immobiliers et rendre visibles ses revendications ? Comment l’usage de certains espaces est-il détourné et mis au service de la promotion de la justice spatiale ? S’inscrivant dans la littérature portant sur les liens entre espace et action collective (Auyero, 2005 ; Cossart et Talpin, 2015), cet article vise à examiner la manière dont les mobilisations pour, par et depuis le territoire, participent à la recomposition de ce dernier.

The goal here is therefore to explore both the appropriation of the neighbourhood by the social movement and the way in which that movement made the transition from specific demands, centred on the occupation, to more general claims relating to the right to remain in the neighbourhood and challenging the post-apartheid urban development model, thereby upsetting the segregated spatial and racial configuration of Cape Town. How does the RTC movement use urban space to challenge its appropriation by real estate developers and make its demands visible? How is the use of certain spaces diverted and employed to promote spatial justice? As a contribution to the literature on the links between space and collective action (Auyero, 2005; Cossart and Talpin, 2015), this article aims to examine the way in which mobilisations for, by and from the territory play a part in the recomposition of territory.

Cette étude repose sur la réalisation de 22 entretiens approfondis – avec des leaders du mouvement et avec des habitants de l’occupation – et de nombreuses observations ethnographiques. L’enquête de terrain a été menée entre septembre et décembre 2018 puis entre avril et mai 2019.

This study is based on 22 in-depth interviews–with leaders of the movement and with residents of the occupation–and numerous ethnographic observations. The fieldwork was conducted between September and December 2018 and again between April and May 2019.

Encadré 1 : Les conditions de l’enquête en milieu militant

Box 1: Conducting research in an environment of activism

Enquêter en terrain militant conduit souvent à s’engager dans le groupe et à en épouser la cause (Broqua, 2009). Les leaders de RTC incitent les chercheurs à s’affilier au mouvement (en devenant membre sympathisant à travers le paiement d’une cotisation [2,60 euros environ]) et à s’engager, tout en respectant les limites tacites d’une participation modérée. Pour faire mes preuves et être acceptée au sein du groupe, j’ai pris part aux moments de mobilisation, accompagné les habitants expulsés aux tribunaux et fréquenté les occupants dans leurs activités quotidiennes. Je me suis toutefois gardée de produire des discours ou de participer à l’élaboration des stratégies. Cette prise de distance a permis de me sentir plus à l’aise et de réduire la méfiance de certains leaders à mon égard. Ainsi, j’ai pu mener ma recherche librement et sans être contrainte de restituer des résultats favorables à l’organisation.

Investigating in an activist environment often means engaging with the group and espousing its cause (Broqua, 2009). RTC’s leaders encourage researchers to join the movement (by becoming a sympathising member and paying a subscription [around €2.60]) and to be engaged, while respecting the tacit limits of moderate participation. To prove myself and be accepted into the group, I took part in occasions of mobilisation, accompanied evicted residents to court and spent time with the occupiers in their daily activities. However, I refrained from making speeches or participating in the development of strategies. Maintaining this distance made me feel more at ease and reduced the mistrust felt towards me by some of the leaders. In this way, I was able to conduct my research freely and without being obliged to report findings that were favourable to the organisation.

Pour mieux cerner la mobilisation des habitants de Woodstock, j’organise mon propos en trois temps. La première partie revient sur la transformation du quartier et montre comment les mutations sociales et spatiales engendrées par la gentrification constituent une entrave à la formation du mouvement social. La deuxième décrypte les diverses significations de l’occupation de l’ancien hôpital pour ses 950 habitants et pour les leaders du mouvement. Solution d’urgence et stratégie de lutte, l’occupation s’inscrit dans la continuité des mobilisations contre l’apartheid. La troisième partie analyse les stratégies d’action en dehors de l’ancien hôpital. Actions judiciaires et contestations de rue permettent de déplacer les revendications du mouvement vers le centre-ville et de devenir une lutte pour le droit à la ville.

To contribute to a better understanding of the mobilisation of the residents of Woodstock, I will structure my account into three parts. The first looks back at the transformation of the district and shows how the social and spatial changes brought about by gentrification hampered the formation of a social movement. The second delves into the various meanings of the occupation of the former hospital for its 950 inhabitants and for the leaders of the movement. As an emergency solution and a fighting strategy, the occupation maintains a continuity with earlier anti-apartheid mobilisations. The third section looks at strategies for action beyond the former hospital. Legal action and street protests shifted the movement’s representations to the city centre and turned them into a fight for the right to the city.

De l’espace-obstacle à l’espace comme principale ressource : la formation de Reclaim the City à Woodstock

From space as an obstacle to space as primary resource: the formation of Reclaim the City in Woodstock

La gentrification, une entrave à l’action collective

Gentrification, a barrier to collective action

Le processus de gentrification commence à Woodstock à la fin des années 1980. S’il est documenté dès 1993, les catégories populaires du quartier ne se mobilisent contre qu’à partir de 2016 sous l’égide du mouvement social RTC. Comment comprendre cette mobilisation tardive ?

The gentrification process began in Woodstock in the late 1980s. Although it has been documented since 1993, the district’s working-class population did not mobilise against it until 2016, under the aegis of the RTC social movement. Why this delay in mobilising?

En 1991, la promulgation de la fin du Group Areas Act[1] conduit de nombreux Coloureds et Blancs[2] de classe moyenne à quitter les Cape Flats, townships distants du centre-ville, pour s’installer à Woodstock (Teppo et Millstein, 2015). Les propriétaires locaux identifient ce remplacement de la classe travailleuse par des locataires de classes moyennes (Visser et Kotze, 2008) et rénovent leurs logements afin d’augmenter la valeur des loyers. Auparavant centrée sur l’industrie portuaire et textile, l’économie du quartier se tertiarise, notamment autour du secteur créatif qui attire artistes et jeunes diplômés, mais exclut les personnes peu qualifiées. Certaines familles fragilisées par la fermeture des usines et la hausse des loyers sont contraintes de déménager vers des logements plus abordables ou de quitter le quartier. Les paysages urbains et les formes résidentielles changent : les maisons victoriennes sont rénovées, affublées de systèmes de sécurité et clôturées par de hauts murs.

In 1991, the promulgation of the end of the Group Areas Act[1] led many middle-class Coloureds and whites[2] to move from the Cape Flats, townships a long way from the city centre, to Woodstock (Teppo and Millstein, 2015). Local landlords became aware of this replacement of working-class by middle-class tenants (Visser and Kotze, 2008) and renovated their homes to increase the value of the rents. Previously centred on the port and textile industries, the district’s economy became increasingly service-oriented, particularly around the creative sector, which attracted artists and young graduates but excluded the low-skilled. Some families made vulnerable by the closure of factories and rising rents were forced to move to more affordable accommodation or leave the area. Urban landscapes and residential forms changed: Victorian houses were renovated, fitted with security systems and surrounded by high walls.

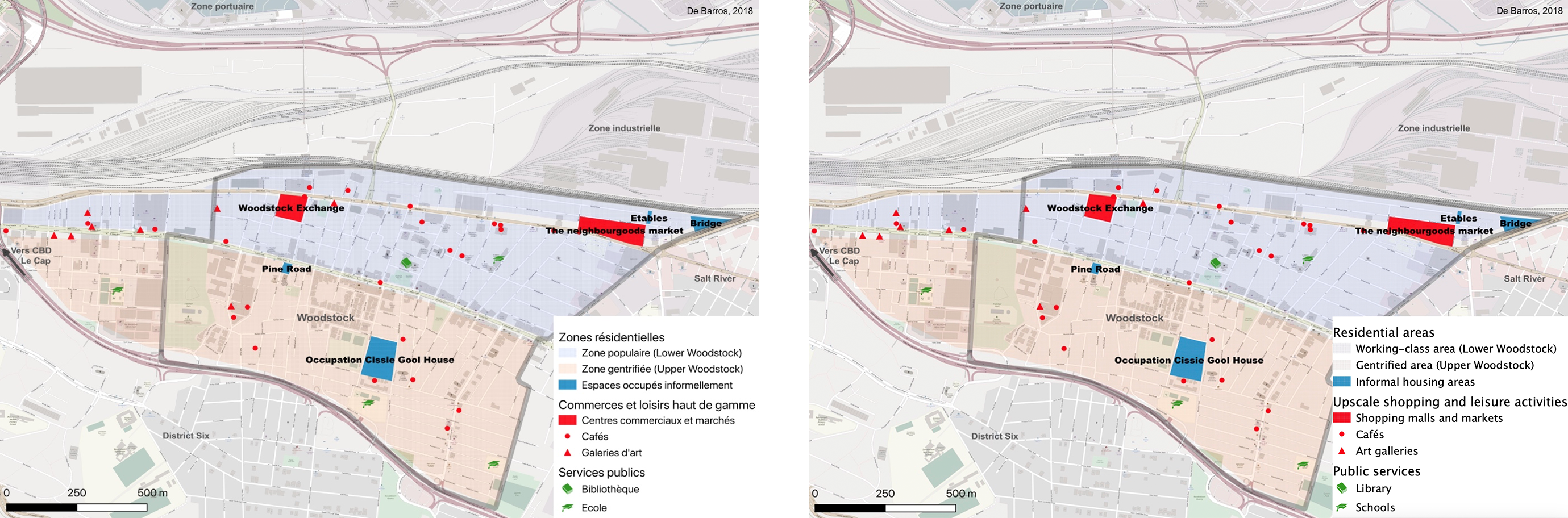

La figure 1 met en évidence les divisions sociospatiales induites par le processus de gentrification à Woodstock. Elle éclaire le développement du secteur tertiaire (commerces, loisirs de luxe) notamment dans la partie basse du quartier (Lower Woodstock), zone la plus populaire où se concentrent les investissements immobiliers. Albert Road, axe reliant ce quartier au centre-ville, est bordé de sites industriels rénovés qui regroupent désormais antiquaires, marchands d’arts et centres commerciaux haut de gamme.

Figure 1 shows the socio-spatial divisions created by the gentrification process in Woodstock. It sheds light on the development of the tertiary sector (retail, luxury leisure), particularly in the lower part of the district (Lower Woodstock), the most working-class section where property investments are concentrated. Albert Road, the axis linking this district to the city centre, is lined with renovated industrial sites that are now home to antique shops, art dealers and upmarket shopping centres.

Figure 1 : La gentrification à Woodstock © Margaux de Barros, 2018

Figure 1: Gentrification in Woodstock © Margaux de Barros, 2018

La hausse progressive du coût de l’immobilier dans le Lower Woodstock conduit les ménages populaires qui y résident à trouver des solutions précaires et souvent instables : déménager vers d’autres logements alors suroccupés, habiter un logement informel pour rester dans le quartier, accepter les propositions de relogement éloigné éventuellement formulées par la municipalité, vivre temporairement dans un véhicule ou dans la rue, comme cela a été le cas pour plusieurs enquêtés. La gentrification conduit ainsi à la juxtaposition d’espaces fortement segmentés socialement. La distance sociale entre résidents d’un même quartier est exacerbée par la multiplication du nombre d’évictions, la survie difficile des classes populaires (notamment dans des lieux occupés de façon informelle, en bleu sur la figure 1), le maintien sur place de catégories sociales défavorisées et la hausse du nombre de ménages aisés. Les Temporary Resettlement Areas, construites en 2007 à la périphérie pour loger les victimes de catastrophes naturelles ou les sans domiciles fixes, sont l’unique option de logement formulée par les pouvoirs publics et sont vivement critiquées (Ranslem, 2015 ; Levenson, 2017).

The gradual rise in the cost of housing in Lower Woodstock led the working-class households living there to look for precarious and often unstable solutions: moving to other, already over-occupied housing, living in informal accommodation in order to stay in the district, accepting any offers of out-of-town rehousing made by the council, living temporarily in a vehicle or on the street, as was the case for several research participants. Gentrification thus led to the juxtaposition of highly socially segmented areas. The social distance between residents of the same neighbourhood was exacerbated by the growing number of evictions, the survival difficulties experienced by working-class people (particularly in informally-occupied premises, shown in blue in figure 1), the fact that disadvantaged social categories stayed put and the increase in the number of well-off households. The Temporary Resettlement Areas, built on the outskirts in 2007 to house victims of natural disasters or the homeless, were the only housing option made available by the authorities and were heavily criticised (Ranslem, 2015; Levenson, 2017).

Contrairement aux habitants de nombreux townships qui peuvent compter sur un réseau communautaire et militant relativement dense né de la lutte contre l’apartheid (Tournadre, 2014), les classes populaires de Woodstock ne peuvent guère s’appuyer sur ce type de solidarité. Trois motifs principaux, liés à la configuration spatiale de ce quartier et aux conditions socio-économiques des enquêtés, permettent de mieux saisir l’émergence tardive de cette contestation des habitants contre les expulsions.

Unlike the inhabitants of many townships who could count on a relatively dense community and activist network born of the struggle against apartheid (Tournadre, 2014), the working-class population of Woodstock could hardly rely on this type of solidarity. Three main reasons, linked to the spatial configuration of this neighbourhood and the socio-economic conditions of the people interviewed, help to explain the time it took for residents to begin to protest against evictions.

Le premier motif concerne la temporalité et la dispersion des expulsions dans l’espace du quartier. Alors que les habitants affectés par un phénomène de déplacement collectif peuvent capitaliser sur le partage d’expériences communes vécues comme injustes pour entrer dans l’action collective (Erdi Lelandais, 2016), les résidents des quartiers gentrifiés ne sont pas menacés au même endroit, en même temps ni par les mêmes acteurs. Certains agents qui participent à la gentrificatrication, tels que les promoteurs immobiliers (en plus des propriétaires) s’avèrent complexes à identifier. Ainsi, le regroupement d’habitants est plus ardu à réaliser que dans des contextes d’expulsions collectives.

The first was the timing and dispersed nature of evictions in the neighbourhood. While residents affected by collective displacement can capitalise on shared experiences of injustice to take collective action (Erdi Lelandais, 2016), residents of gentrified neighbourhoods are not threatened in the same place, at the same time, or by the same actors. Some of the agents involved in gentrification, such as real estate developers (as well as landlords), are difficult to identify. It was therefore more difficult to bring residents together than in the case of mass evictions.

Le deuxième renvoie à la situation économique des habitants et à l’isolement engendré par l’expulsion. Ceux affectés par la hausse des loyers portent le fardeau de leur situation économique, sont rendus et se rendent responsables de leur expulsion. En effet, de nombreux habitants témoignent des sentiments de honte et de culpabilité suscités par l’impossibilité de s’acquitter de leur loyer. De plus, l’arrivée de nouveaux voisins aux propriétés sociales supérieures modifie la composition du voisinage et complique la création d’un réseau de solidarité comme en témoigne Rosa[3] lorsque je l’interroge sur l’aide potentielle apportée par ses voisins lors de son expulsion :

The second reason relates to the residents’ economic situation and the isolation caused by eviction. Those affected by rent rises bore the burden of their financial situation, and were both blamed and blamed themselves for their eviction. Indeed, many residents spoke of the shame and guilt they felt at not being able to pay their rent. Moreover, the arrival of new neighbours of higher social status changed the make-up of the neighbourhood and made it harder to create a network of solidarity, as Rosa[3] testified when I asked her about the potential help provided by her neighbours when she was evicted:

« Non, je n’ai pas l’habitude de me promener et de discuter avec les gens du coin parce que toutes les maisons ici ont été achetées par des propriétaires qui vivent dans ces maisons. Ma maison était la seule qui soit encore louée. » (Rosa, 47 ans, mère de 3 enfants et vendeuse en boulangerie)

“No. I don’t usually walk around and talk to people because all that homes in our street is now privately owned. The owners are in the houses. It was only our house that was rented.” (Rosa, 47, mother of 3, a shopworker in a bakery)

L’affaiblissement des liens de voisinage, combiné à une responsabilisation du pauvre (Piven et Cloward, 1979) ont entravé pendant plus de deux décennies la mise en place d’une action collective.

For more than two decades, the weakening of neighbourhood ties, combined with the blame directed at the poor (Piven and Cloward, 1979), hampered the development of collective action.

Le troisième motif a trait à la faible visibilité de la gentrification. Si à Woodstock ce phénomène est documenté dès 1993 (Garside, 1993), il est relativement peu étudié par les chercheurs en sciences sociales avant 2010. Après l’apartheid, les impératifs de recherche dictés par les organismes publics ou les ONG se centrent sur les espaces de relégation comme les townships. Les recherches s’attellent à identifier les problèmes sociaux dans les périphéries afin d’y améliorer les conditions de vie, mais se détournent des processus de gentrification en cours à proximité des centres-villes (Visser et Kotze, 2008). Or, la mobilisation d’acteurs externes peut être cruciale pour faire émerger l’action collective dans des quartiers défavorisés. Jack, fait part du déplacement de regard réalisé par son ONG :

The third reason relates to the low visibility of gentrification. Although the phenomenon of gentrification had been documented in Woodstock as early as 1993 (Garside, 1993), it received relatively little attention from social science researchers before 2010. After apartheid, the research imperatives dictated by public bodies and NGOs focused on areas of exclusion such as the townships. Research focused on identifying social problems in the peripheral areas in order to improve living conditions there, but shied away from the gentrification processes underway in the vicinity of city centres (Visser and Kotze, 2008). However, the mobilisation of outside agents can be crucial to the emergence of collective action in disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Jack reports on his NGO’s shift of focus:

« Et donc, on a réalisé que si on s’investissait principalement à la périphérie de la ville, on ne remettrait jamais en question le pouvoir qui reproduit les inégalités dans notre ville […]. Donc, on a fait un choix conscient : au lieu de se focaliser sur la périphérie, on allait mettre notre attention sur le centre-ville et perturber leur territoire qui a beaucoup plus de valeur ! » (Jack, leader de RTC et dirigeant de Ndifuna Ukwazi)

“And we realised: ‘but if we put all our energy into the periphery, we will never transform the power that replicates the inequality in our city!’ […]. So we made a conscious decision that instead of focusing on the periphery we would shift our attention to the centre and we would try to challenge and disrupt their land, which has much more value!” (Jack, RTC leader and head of Ndifuna Ukwazi)

En centrant leur attention sur la périphérie, les organismes étatiques ou les ONG reproduisent les mécanismes de relégation des classes populaires. Ces politiques d’assistance centrées sur les townships permettent de rendre supportables les conditions de vie des pauvres urbains, mais constituent aussi, parfois involontairement, un moyen de les contenir à la périphérie, empêchant toute remise en question profonde du modèle ségrégué centre-périphérie dessiné par le régime d’apartheid.

By focusing on the periphery, state bodies and NGOs reproduced the mechanisms of exclusion imposed on working-class South Africans. This emphasis on assisting the townships helped to make the living conditions of the urban poor bearable, but it was also, sometimes unwittingly, a means of keeping them on the outside, preventing any profound challenge to the segregated centre-periphery model drawn up by the apartheid regime.

Ces différents motifs conduisent à penser la mobilisation des classes populaires contre les expulsions comme un phénomène marginal. De nombreux auteurs (Smith, 2002 ; Clerval, 2016 ; Desmond, 2019) ont montré dans des contextes nord-occidentaux que ce sont le plus souvent les classes moyennes et les propriétaires qui se rassemblent pour se saisir des questions urbaines. Compte tenu des diverses entraves à la mobilisation, l’occupation d’un ancien bâtiment public s’avère cruciale dans la formation du mouvement à Woodstock.

For all these reasons, the mobilisation of working-class people against evictions could be seen as a marginal phenomenon. Numerous authors (Smith, 2002; Clerval, 2016; Desmond, 2019) have shown how in the Global North it is more often the middle classes and homeowners who come together to tackle urban issues. Given these various obstacles to mobilisation, the occupation of a former public building proved crucial in the formation of the Woodstock movement.

La campagne Reclaim the City : la jonction d’habitants expulsés et des militants de Ndifuna Ukwazi

The Reclaim the City campaign: evicted residents and Ndifuna Ukwazi activists join forces

La campagne Reclaim the City naît en 2016 sous l’impulsion de l’ONG Ndifuna Ukwazi[4] (NU) et d’anciens membres du Rainbow Housing Group, qui réunit les travailleurs domestiques du quartier de Sea Point, dont certains ont été affiliés à l’African National Congress (ANC)[5] au début des années 1990. La campagne est d’abord lancée pour contester la vente d’une ancienne école publique, la Tafelberg School, située dans le centre-ville du Cap, et y imposer la construction de logements sociaux[6]. Ces deux groupes occupent le terrain pendant quarante-huit heures, brandissant pour la première fois le slogan « Land for people, not for profit ». Le succès de cette campagne et l’enthousiasme suscité par les premiers épisodes protestataires incitent le mouvement à intensifier la lutte.

The Reclaim the City campaign was launched in 2016 by the NGO Ndifuna Ukwazi[4] (NU) and former members of the Rainbow Housing Group, which brought together domestic workers from the Sea Point neighbourhood, some of whom were affiliated to the African National Congress (ANC) in the early 1990s.[5] The campaign was initially launched to oppose the sale of the Tafelberg School, a former public school located in Cape Town city centre, and to demand the construction of affordable housing.[6] These two groups occupied the site for forty-eight hours, launching the slogan “Land for people, not for profit”. The success of this campaign and the enthusiasm generated by the initial protests encouraged the movement to step up the fight.

Dans le même temps, la multiplication des expulsions à Bromwell Street dans le quartier de Woodstock attire l’attention de NU. La campagne RTC se focalise sur les expulsions en cours dans cette rue populaire. En avril 2016, les chercheurs de NU dénoncent le processus d’évictions sur les réseaux sociaux. Le Law Center, le service juridique, de NU assiste juridiquement les quarante familles de Bromwell Street menacées d’expulsion par le promoteur immobilier Woodstock Hub.

At the same time, the growing number of evictions in Bromwell Street in the Woodstock district attracted the attention of NU. The RTC campaign focused on the evictions then underway in this working-class street. In April 2016, NU researchers launched a social media attack on the eviction process. NU’s Law Center provided legal assistance to forty Bromwell Street families threatened with eviction by property developer Woodstock Hub.

Deux préoccupations dessinent le contour de l’organisation qui émerge : faire cesser la vente de terrains publics localisés au centre-ville et dans les quartiers péricentraux pour y encourager la construction de logements sociaux et mettre un terme aux expulsions. Le mouvement se fonde notamment sur l’expertise des chercheurs de NU ; il s’agit de rendre publiques à la fois les ventes controversées et les revendications portées par le mouvement social pour mettre un terme aux expulsions.

Two concerns shaped the emerging organisation: stopping the sale of public land in the city centre and inner suburbs in order to push for the construction of affordable housing, and putting an end to evictions. The movement depended in particular on the expertise of NU researchers: the aim was to publicise both the controversial sales and the social movement’s demands for an end to the evictions.

En mars 2017, profitant du tournage d’un film d’horreur réalisé par des étudiants dans l’ancien hôpital de Woodstock, loué par la municipalité à cette occasion, les membres de l’ONG se font passer pour l’équipe de tournage, s’infiltrent et occupent les lieux. D’abord pensée comme un coup d’éclat, l’occupation se pérennise. Après une semaine, viennent s’y joindre des sans-abri, ainsi que des membres de NU et leurs amis universitaires. Une réunion conjointe est organisée après dix jours : la majorité des habitants itinérants ou en situation d’expulsion souhaitent rester et transformer ce lieu en espace de vie. Ils nettoient, réparent, aménagent et subdivisent les espaces pour les convertir en logements et lieux de militantisme.

In March 2017, taking advantage of the shooting of a horror film made by students in the old Woodstock hospital, which had been rented by the municipality for the occasion, members of the NGO posed as film crew and infiltrated and occupied the premises. Initially conceived as an awareness-raising stunt, the occupation became permanent. After a week, they were joined by homeless people, members of NU and their university friends. A joint meeting was organised after ten days: the majority of the homeless residents or those facing eviction wanted to stay and convert the site into a living space. They cleaned, repaired, equipped and subdivided the spaces to convert them into homes and spaces of activism.

La campagne RTC se transforme en mouvement social, indépendant de NU. Des leaders sont élus pour rédiger la constitution du mouvement, laquelle définit ses revendications et régit les règles de vie à l’intérieur du lieu occupé. Le groupe se fait également une place au sein du paysage contestataire capétonien. Il intègre le mouvement Unite Behind, coalition de plus de vingt mouvements locaux créée en 2016 pour défendre collectivement la justice sociale. Cette convergence des luttes garantit à RTC l’acquisition de nouvelles ressources, logistiques et expertes, indispensables pour gagner en visibilité.

The RTC campaign was transformed into a social movement, independent of NU. Leaders were elected to draft the movement’s constitution, which defined its demands and the rules of life inside the occupied site. The group also carved out a place for itself on the Cape Town protest scene. It joined the Unite Behind movement, a coalition of more than twenty local movements created in 2016 to collectively pursue social justice. This convergence of struggles enabled RTC to acquire new resources in terms of logistics and expertise, which were essential if it was to gain greater visibility.

Occuper pour lutter et rester, l’inscription territoriale du mouvement

Occupy to fight and stay: the movement’s territorial embeddedness

L’occupation comme stratégie et ressource sociogéographique

Occupation as a socio-geographic strategy and resource

L’occupation de l’hôpital de Woodstock devient le lieu d’ancrage du mouvement social. Elle s’avère cruciale tant pour la formation que pour la pérennisation de ce dernier. Elle s’affirme également comme un moyen de redresser les injustices spatiales vécues par les habitants et leurs familles pendant et après la période d’apartheid.

The occupation of Woodstock hospital became the home base of the social movement. It was crucial both to its formation and its long-term future. It was also a means of righting the spatial injustices experienced by the residents and their families during and after the apartheid era.

L’inscription spatiale du mouvement répond, dans un premier temps, à la situation d’urgence dans laquelle se trouvent les habitants expulsés. Ils vivent dans le quartier depuis longtemps et y ont tissé un vaste réseau d’interconnaissances. Désireux d’y rester pour préserver leurs liens sociaux, l’accès aux services publics et aux emplois, ils s’adressent à RTC dans l’espoir de résoudre leur problème de logement. Ils introduisent alors une demande de logement au sein de l’ancien hôpital occupé, laquelle est ensuite examinée par les leaders. Une fois installés, ils doivent, en contrepartie, participer aux activités du mouvement, telles que les manifestations, les réunions ou les cours d’éducation populaire.

The movement’s spatial embeddedness was initially a response to the emergency situation in which the evicted residents found themselves. They had lived in the area for a long time and had built up a large network of acquaintances. Wanting to remain there to preserve their social ties and access to public services and jobs, they turned to RTC in the hope of resolving their housing problem. They would submit an application for accommodation in the occupied former hospital, which would be examined by the leaders. Once settled in, they had, in return, to take part in the movement’s activities, such as demonstrations, meetings or popular education courses.

La présence de 950 habitants dans cette partie du quartier ne représente pas seulement un coup de force symbolique, il s’agit aussi d’un moyen de gripper certains mécanismes de la gentrification. En effet, la présence d’habitants aux pratiques informelles et à la fréquentation populaire de la rue contribue à enrayer l’appropriation du quartier par les gentrifieurs (Giroud, 2007 ; Clerval, 2011). Ainsi, en récupérant une portion d’espace dans la zone la plus gentrifiée de Woodstock, le mouvement participe à la recomposition sociale du territoire et œuvre au maintien des franges populaires.

The presence of 950 residents in this part of the district not only represented a symbolic show of strength, but was also a way of jamming up certain gentrification mechanisms. Indeed, the existence of residents with informal lifestyles and a working-class street presence helped to prevent gentrifiers from taking over the neighbourhood (Giroud, 2007; Clerval, 2011). In this way, by reclaiming a portion of space in the most gentrified area of Woodstock, the movement was participating in the social recomposition of the area and working to maintain working-class fringes.

L’occupation pourvoit au mouvement un ancrage spatial et une base routinière à partir desquels il devient possible d’organiser la lutte et de susciter l’engagement auprès des habitants. Fabrice Ripoll (2008) a montré l’importance pour les mouvements protestataires de disposer d’un espace à soi pour mettre en place des rencontres et des réunions. Deux vastes salles sont mises à disposition pour ces échanges. La première est réservée à l’organisation de fêtes, de funérailles ou d’offices religieux et la seconde sert exclusivement aux réunions et aux cours d’éducation populaire. Ces espaces servent donc à resserrer les liens entre résidents autour d’événements qui jalonnent la trajectoire de chacun, à planifier les actions de lutte et à instiller une culture politique aux habitants. L’acquisition des modes de pensée du mouvement social ainsi que le partage d’instants de convivialité contribuent conjointement à la cohésion du groupe.

Occupation provided the movement with a spatial anchor and a stable base from which to organise the struggle and engage local residents. Fabrice Ripoll (2008) has shown how important it is for protest movements to have their own space in which to hold events and meetings. Two large rooms were made available for these activities. The first was set aside for celebrations, funerals or religious services, while the second was used exclusively for meetings and popular education courses. These spaces thus helped to strengthen links between residents around events that punctuated each person’s routines, to plan protest actions and to develop the residents’ political culture. Acquiring the social movement’s ways of thinking and enjoying social events together contributed to group cohesion.

En prenant part aux affaires de la vie locale, une partie des habitants se socialisent aux enjeux politiques. S’ils s’impliquent inégalement dans les activités militantes, la majorité d’entre eux participent aux tâches quotidiennes (bricolage, jardin collectif) et mobilisent leurs compétences pour améliorer leur qualité de vie sur place. Comme plusieurs chercheurs l’ont observé dans d’autres squats politiques (Yates, 2015 ; Nez, 2017 ; Caciagli, 2019), ces pratiques soudent les liens entre habitants et renforcent leur estime de soi, fragilisée par les expulsions.

By joining in with local events, some of the residents developed their political awareness. Although they differ in their engagement in activism, the majority of them take part in everyday tasks (DIY, communal gardening) and use their skills to improve their quality of life on site. As several researchers have observed in other political squats (Yates, 2015; Nez, 2017; Caciagli, 2019), these practices strengthen the bonds between residents and boost their self-esteem, which had been undermined by the evictions.

La mémoire spatiale comme ferment de l’action collective

Spatial memory as the basis for collective action

Pour les leaders et une partie des résidents, rester dans le quartier constitue aussi un moyen de lutter contre des injustices ancrées spatialement et historiquement dans la ville du Cap. En relatant leur expérience d’expulsion, ils revisitent finalement toute leur mémoire familiale. C’est ce que j’observe lors de l’Heritage Day Memory Walk, organisée dans le Lower Woodstock par RTC le 24 septembre 2019. Cet événement réunit près de 80 habitants de l’occupation. Une vingtaine d’entre eux (majoritairement des enfants) sont munis de pancartes sur lesquelles on peut lire : « La gentrification m’a volé ma maison », « Je vivais ici », « Woodstock est aussi à nous ». Ils s’arrêtent devant les logements d’où plusieurs d’entre eux ont été expulsés, narrent leurs histoires individuelles puis entonnent des chants de lutte contre l’apartheid. Yvonne, expulsée de son logement familial en 2009, se place devant un haut immeuble en construction, accompagnée de ses filles et de ses petites-filles, elle prend la parole et exprime son émotion :

For the leaders and some of the residents, staying in the neighbourhood is also a way of fighting against injustices that are spatially and historically rooted in Cape Town. In recounting their experience of expulsion, they are revisiting their entire family memory. This is what I observed at the Heritage Day Memory Walk, organised in Lower Woodstock by RTC on 24 September 2019. This event brought together nearly 80 occupation residents. Around twenty of them (mostly children) carried signs that read: “Gentrification stole my house”, “I used to live here”, “Woodstock is ours too”. They stopped in front of the homes from which many of them had been evicted, told their personal stories and then sang anti-apartheid songs. Yvonne, who had been evicted from her family home in 2009, stood in front of a tall building under construction. Accompanied by her daughters and granddaughters, she spoke out and expressed her emotion:

« J’ai vécu ici pendant 34 ans. Ce n’était pas aussi violent que les gens le pensent. C’était un très bel endroit où élever une famille. Nous n’avons pas pu rester, car la location était trop chère donc nous devions partir et nous avons finalement été jetés dehors. Et maintenant, voilà ce qu’ils sont en train de construire, un nouveau grand building dans lequel nous n’avons pas notre place. J’ai vécu District six et je revis District six. (Yvonne, 68 ans, retraitée)

“I lived here for 34 years […]. It wasn’t as violent as people think. It was a very nice place to raise a family […], we couldn’t stay because the rent was too expensive so we had to leave and they finally kicked us out. And now this is what they are building, a huge new building that we don’t fit in. I lived in District Six, I’m living District Six again.” (Yvonne, 68, retired)

Le registre nostalgique du discours d’Yvonne associe les expulsions à la fin d’un âge d’or qui prend à rebours les représentations négatives associées au quartier (« Ce n’était pas aussi violent que les gens le pensent »). L’expulsion réactive ainsi des logiques identitaires, comme en témoignent ces propos, « nous n’avons pas notre place », qui traduisent un sentiment d’exclusion à la fois raciale et sociale, en référence directe à l’expérience traumatisante de District Six[7] (Houssay-Holzschuch, 1998 ; Adhikari, 2005). Susanna poursuit cette référence aux expulsions de l’apartheid :

The nostalgic tone of Yvonne’s speech likens the evictions to the end of a golden age, which runs counter to the negative images associated with the neighbourhood (“It wasn’t as violent as people think”). The expulsion thus reactivates identity-based processes, as evidenced by the words “we don’t belong here”, which reflect a feeling of exclusion that is both racial and social, in direct reference to the traumatic experience of District Six[7] (Houssay-Holzschuch, 1998; Adhikari, 2005). Susanna continues this reference to apartheid expulsions:

« Nous sommes ici pour dire que nous existons. La gentrification est juste un mot moderne pour dire “Group Areas Act”. Il y a toujours le Group Areas Act et nous devons y mettre un terme, maintenant. Comment la municipalité et le gouvernement peuvent-ils vendre des terrains publics à des promoteurs immobiliers ? Les terrains publics doivent rester publics. J’ai vécu dans deux maisons de cette rue et je pense que c’est mon droit et que c’est NOTRE droit de vivre à Woodstock. » (Susanna, leader de RTC)

“We are here to say that we exist. Gentrification is just a modern word to say Group Areas Act. It is still the Group Areas Act and we need to stop that now. How can the city and the government sell public land to private developers? Public land should remain public. I lived in two houses in that street, and I feel that it is my right and that it is OUR right to live in Woodstock.” (Susanna, RTC leader)

Prenant la parole après un long moment d’émotion, Susanna tente de transformer la douleur en griefs politiques. Elle dénonce la responsabilité des pouvoirs publics et exalte un sentiment d’unité en insistant sur un « nous » qui désigne à la fois les personnes expulsées, les membres des classes populaires et plus largement la communauté coloured autrefois majoritaire dans cette partie de la ville.

Coming forward to speak after a long emotional moment, Susanna tries to transform the pain into political grievances. She points the finger at the public authorities and exalts a feeling of unity by insisting on a “we” that refers to the people evicted, the working-class population and, more broadly, the coloured community that was once the majority in this part of the city.

Avec l’organisation de cet événement, les membres de RTC transforment ce jour de célébration nationale en commémoration locale, conçue pour donner la parole aux expulsés, célébrer les instants vécus dans le quartier et affirmer leur présence. La nostalgie partagée renforce une certaine ferveur collective, un sentiment de devoir lutter ensemble autour d’une identité partagée pour préserver le quartier. Cette mise en scène d’une appartenance au quartier, qui suscite de fortes émotions de colère et de nostalgie, permet de souder le groupe et prédispose les habitants à s’engager (Traïni, 2010 ; Portelli, 2014) autour d’une même cause. Ce recours à l’espace comme levier d’engagement est d’autant plus nécessaire que la plupart des habitants ne sont pas socialisés politiquement. La prise de conscience d’une appartenance commune au quartier et le passage d’une expérience d’exclusion vécue comme individuelle et humiliante à un phénomène collectif et injuste est ainsi facilitée par les entrepreneurs de mobilisation qui ont bien compris que la relation affective au quartier stimule le sentiment d’appartenance et donne un sens commun au groupe.

By organising this event, the members of RTC transformed this day of national celebration into a local commemoration, intended to give a voice to the evictees, to celebrate their experiences in the neighbourhood and to affirm their presence. Shared nostalgia reinforces a certain collective fervour, a feeling of having to fight together around a shared identity to preserve the neighbourhood. This staging of a sense of belonging to the neighbourhood, which arouses strong emotions of anger and nostalgia, helps to bind the group together and predisposes residents to commit themselves (Traïni, 2010; Portelli, 2014) to the same cause. This use of space as an instrument of engagement is all the more necessary in that most of the residents are not politically socialised. A shared sense of belonging to the neighbourhood, and the transition from a sense of exclusion felt as individual and humiliating to a community experience of injustice, are thus facilitated by the instigators of the mobilisation, who have clearly understood that an emotional relationship with the neighbourhood stimulates a sense of community and shared purpose to the group.

Enfin, ce sentiment d’appartenance au quartier est corrélé à celui d’appartenance à l’identité coloured, lui-même fondé à partir d’injustices spatiales que partagent de nombreux habitants de l’occupation. Comme l’exposent Elaine Salo (2018) et Christiaan Beyers (2005), l’expérience traumatique des déguerpissements de 1965 et le confinement dans les townships qui leur sont réservés sont une composante importante du sentiment d’appartenance à l’identité coloured. Avant cela, coloureds était une catégorie normative dans laquelle les individus se reconnaissaient peu. C’est en partie par le récit des expulsions et le partage de cette mémoire traumatique dans les townships que les Coloureds commencent à revendiquer leur appartenance à ce groupe, au début des années 1970. En mobilisant notamment les injustices vécues sous l’apartheid en tant que grille de lecture de la gentrification, il s’agit d’associer le quartier à l’identité coloured, née de l’oppression systématisée sous ce régime.

Finally, this sense of belonging to the neighbourhood is correlated with the shared sense of a coloured identity, itself founded on the spatial injustices experienced by many of the occupiers. As Elaine Salo (2018) and Christiaan Beyers (2005) showed, the traumatic experience of the 1965 evictions and confinement to the townships allocated to them are an important component of the sense of possessing shared coloured identity. Before that, coloureds was a normative category with which individuals did not identify. It was partly through the story of the evictions and the sharing of this traumatic memory in the townships that the coloureds began to assert their identification with this group in the early 1970s. By drawing upon the injustices experienced under apartheid as a way of interpreting gentrification, the aim was to associate the neighbourhood with the coloured identity born of the systematic oppression exercised against them under the apartheid regime.

En 2017, l’initiative de renommer l’occupation « Cissie Gool House », du nom d’une militante coloured engagée contre le Parti national pendant l’apartheid, témoigne de la volonté des cadres du mouvement d’inscrire leur action dans la continuité des luttes contre la ségrégation.

In 2017, the initiative to rename the occupation “Cissie Gool House”, after a coloured activist who opposed the National Party during apartheid, underlined the movement’s leaders’ desire to situate their action in continuity with the struggles against segregation.

S’approprier la ville en se mobilisant

Taking ownership of the city by mobilising

De l’occupation au droit à la ville

From occupation to the right to the city

La mobilisation des habitants en dehors des murs du lieu occupé est nécessaire pour faire avancer des revendications et rendre visible le mouvement. Comme indiqué précédemment, une des demandes principales est la construction de logements sociaux au centre-ville. Elle est corrélée à celle portant sur la fin des expulsions et vise à obtenir, pour les classes populaires, la possibilité d’habiter à proximité du principal bassin d’emploi. Pour RTC, la construction de logements sociaux centraux et péricentraux constituerait une solution viable pour faire face aux expulsions et transformer la composition sociale et raciale homogène de ces espaces, presque inchangée depuis la fin de l’apartheid.

It was necessary for the residents to mobilise beyond the walls of the occupied site in order to push forward their demands and give visibility to the movement. As mentioned above, one of the main demands was for affordable housing to be built in the city centre. It was correlated with the campaign to put an end to evictions and sought to ensure that working-class populations would be able to live close to the main job catchment area. For RTC, the construction of affordable housing in the areas in and around the centre of the city constituted a viable solution for dealing with the evictions and transforming the homogeneous social and racial composition of these areas, which had remained virtually unchanged since the end of apartheid.

En effet, la fragmentation de la ville du Cap n’a guère été résorbée par les programmes de logements mis en place à partir de 1994. L’austérité budgétaire est appliquée et la restructuration économique et sociale de la ville est confiée à des entreprises privées et à des partenariats public-privé (Oldfield, 2002). Afin de construire massivement des logements sociaux, les sociétés immobilières sélectionnent des terres situées dans la périphérie de la ville (Dubresson et Jaglin, 2011), intensifiant ainsi l’étalement urbain et perpétuant l’organisation spatiale de l’apartheid. Le foncier localisé à proximité du centre urbain est trop onéreux et la métropole du Cap refuse d’utiliser les quelques terres[8] qu’elle y possède pour la construction de logements sociaux. Les habitants de Woodstock sont, pour la plupart, inscrits sur une liste d’attente pour accéder à un logement social, et ce, parfois depuis 1994[9]. L’opacité du traitement de ces listes et l’inertie bureaucratique exaspèrent les résidents. L’accès au logement est étroitement lié à l’expérience de l’attente, commune à tous les enquêtés. Cet état « perpétuellement temporaire » (Yiftachel, 2009) contraint les habitants à opter pour des solutions de logement intermédiaires, précaires et informelles (Oldfield et Greyling, 2015), à l’image de l’occupation de l’ancien hôpital.

The fragmentation of the city of Cape Town was scarcely affected by the housing programmes introduced from 1994 onwards. Fiscal austerity was enforced and the economic and social restructuring of the city was entrusted to private companies and public-private partnerships (Oldfield, 2002). In order to build affordable housing on a massive scale, real estate companies selected land on the outskirts of the city (Dubresson and Jaglin, 2011), thereby intensifying urban sprawl and perpetuating the spatial organisation of apartheid. Land close to the urban centre was too expensive, and Cape Town Metropolitan Municipality refused to use the little land it had to build affordable housing.[8] Most Woodstock residents were on a waiting list for affordable housing, in some cases since 1994.[9] The residents were exasperated by the lack of transparency in the processing of these lists and by bureaucratic inertia. Access to housing was closely linked to the experience of waiting, common to all the respondents. This “perpetually temporary” state (Yiftachel, 2009) forced the inhabitants to opt for intermediate, precarious and informal housing solutions (Oldfield and Greyling, 2015), such as the occupation of the old hospital.

RTC entend responsabiliser les pouvoirs publics, en l’occurrence la municipalité et la province du Cap, et les obliger à mettre rapidement en œuvre les mesures constitutionnelles décrétées en 1995 portant sur un accès plus équitable au logement et aux services publics. L’action du mouvement s’articule autour de deux volets, celui du droit et celui de la contestation ouverte. À l’instar d’autres mouvements mobilisés pour la justice spatiale (Zhang, 2021), RTC utilise les arènes judiciaires pour faire valoir le droit au logement. Le mouvement assiste les victimes d’expulsion devant les tribunaux et dépose des recours en justice pour empêcher la vente de terrains publics situés au centre-ville. Ces actions judiciaires sont combinées à des actions protestataires. À plusieurs reprises, les membres de RTC occupent les terrains mis en vente par la municipalité et plaident en faveur de la construction de logements sociaux.

RTC’s aim was to hold the public authorities, in this case Cape Town municipality and province, to account and force them to rapidly implement the constitutional measures decreed in 1995 on fairer access to housing and public services. There were two axial components to the movement’s activity: legal action and open protest. Like other movements working for spatial justice (Zhang, 2021), RTC entered the legal arena to assert the right to housing. The movement supports victims of eviction in the courts and takes legal action to prevent the sale of public land in the city centre. These legal moves were combined with protest actions. On several occasions, RTC members occupied land put up for sale by the municipality and called for the construction of affordable housing.

Cette articulation du cause-lawyering[10] à la protestation permet de ne pas confiner la lutte aux tribunaux, d’exercer une pression constante sur la municipalité et de mettre le problème de l’accès au logement à l’agenda politique.

This link between cause-lawyering[10] and protest means that the struggle is not confined to the courts, that constant pressure is exerted on the municipality and that the problem of access to housing remains on the political agenda.

En contestant la production urbaine au centre-ville, et l’entre-soi blanc et aisé de ces quartiers, le mouvement interroge le façonnage racial de cet espace, sacralisé avant et pendant l’apartheid comme espace blanc par excellence (Western, 1996 ; Houssay-Holzschuch, 1997). Les demandes passent du droit à rester à Woodstock à celui de s’approprier et d’habiter le centre-ville et les quartiers aisés adjacents. Cette montée en généralité des revendications illustre la quête plus globale d’un droit à la ville, lequel « légitime le refus de se laisser écarter de la réalité urbaine par une organisation discriminatoire et ségrégative » (Lefebvre, 1968, p. 21). En se rassemblant dans des espaces centraux pour affirmer leur droit au logement, les militants ouvrent une brèche. L’appropriation temporaire d’un lieu débouche sur une appropriation durable de l’espace urbain en général. Protester contre la valorisation mercantile des espaces centraux a également pour objectif de proposer et d’imposer d’autres finalités à ces espaces, correspondant davantage aux besoins des citadins.

By challenging urban production in the city centre and the white, affluent, “insider” nature of these neighbourhoods, the movement challenges the racial shaping of this space, which was sanctuarised before and during apartheid as the white area par excellence (Western, 1996; Houssay-Holzschuch, 1997). The demands ranged from the right to stay in Woodstock to the right to own a home and live in the town centre and adjacent affluent areas. This widening of the demands illustrates the more global quest for a right to the city, which “legitimises the refusal to allow oneself to be excluded from urban reality by a discriminatory and segregative organisation” (Lefebvre, 1968, p. 21). By gathering in central locations to assert their right to housing, the activists were opening a breach. The temporary appropriation of one place led on to a lasting appropriation of urban space in general. The aim of protesting against the commercial exploitation of central areas was also to propose and impose other purposes for these areas, more in line with the needs of city dwellers.

Les occupations temporaires et l’escrache comme modalités d’action collective

Temporary occupations and escrache as forms of collective action

Les occupations temporaires de bâtiments et de terrains publics situés au centre-ville représentent le mode d’action externe privilégié du mouvement. Elles visent à interpeller la puissance publique et à mettre en scène les demandes de reconnaissance. La présence de nombreux militants dans un même espace donne de la visibilité au mouvement et constitue une forme de réappropriation collective (Bleil, 2011). Ces occupations temporaires entrent en continuité avec l’occupation durable de l’ancien hôpital de Woodstock. Elles se font dans trois types d’espaces : ceux représentatifs de la puissance publique (la municipalité), ceux gérés par des entreprises publiques fournissant des services défaillants (siège de Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa, compagnie ferroviaire nationale) ou des espaces publics centraux destinés aux loisirs et dont l’usage récréatif est considéré comme abusif (terrains de golf, bowling) puisqu’ils sont loués à bas prix à des entités privées. Pendant l’occupation du terrain de bowling, le 1er mai 2018, à Greenpoint, des activistes élèvent un mur sur lequel est inscrit « Municipalité du Cap, construis des logements sociaux ici ! ». En occupant, ils détournent l’usage habituel de ces lieux destinés aux plus aisés et affirment leur présence sur ces territoires.

Temporary occupations of public buildings and land in the city centre are the movement’s preferred form of external action. Their aim is to appeal to the authorities and to publicise their claims for recognition. The presence of large numbers of activists in the same space brings visibility to the movement and constitutes a form of collective reappropriation (Bleil, 2011). These temporary occupations are a continuation of the long-term occupation of the former Woodstock hospital. They take place in three types of space: those representing public power (the municipality), those managed by public companies providing failing services (the headquarters of the Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa, the national railway company), or central public spaces intended for leisure activities and whose recreational use is considered abusive (golf courses, bowling alleys) since they are rented out at low prices to private entities. During the occupation of the bowling green on 1st May 2018 in Greenpoint, activists put up a wall with the words “Cape Town Municipality, build affordable housing here!” on it. By occupying these areas, they divert them from their habitual use by the more affluent and assert their presence in the area.

En plus de ces occupations, les leaders de RTC ont emprunté la pratique des escraches, développée par les militants anti-expulsion de la Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca à Barcelone. Un escrache consiste à protester devant le domicile d’une figure publique dont l’action est ainsi dénoncée, un moyen d’action considéré comme le plus subversif de leur répertoire d’action.

In addition to these occupation events, the RTC leaders borrowed the practice of escraches, developed by the anti-eviction activists of the Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca in Barcelona. In an escrache, protests are staged outside the home of a public figure in order to denounce their actions, a method of protest considered to be the most subversive in their repertoire.

Encadré 2 : Observation d’un escrache à Camps Bay

Box 2: Observation of an escrache at Camps Bay

À 5 heures du matin, je rejoins une partie des militants de RTC devant l’occupation. Nous regagnons ensuite les locaux de NU. Nous buvons un café puis nous nous regroupons au sein de deux taxis collectifs appartenant à des habitants de l’occupation. Nous quittons les bureaux de l’ONG à 6 heures pour rejoindre la maison de Japie Hugo. Directeur général de la planification urbaine de la municipalité du Cap depuis 1996, il participe en 2016 aux négociations concernant la vente à bas coût du site de Site B, terrain situé au centre-ville, à la société immobilière Growthpoint. Il démissionne la même année et obtient un poste de consultant auprès de cette même compagnie. Nous arrivons à Camps Bay, quartier le plus aisé du Cap. La maison imposante de Japie Hugo surplombe la plage. Elle se situe dans un quartier composé de vastes villas (figure 2).

At 5 a.m., I join some of the RTC activists outside the occupation. We then return to the NU offices. We have coffee and then regroup in two shared taxis belonging to residents of the occupation. We leave the NGO offices at 6 a.m. to go to Japie Hugo’s house. As Director General of Urban Planning for the City of Cape Town since 1996, he took part in negotiations in 2016 over the low-cost sale of the Site B site, a plot of land located in the city centre, to the Growthpoint property company. He resigned the same year and obtained a consultancy position with the same company. We arrive in Camps Bay, the most affluent district in Cape Town. Japie Hugo’s imposing house overlooks the beach. It is located in a neighbourhood composed of large villas (figure 2).

Figure 2 : Panorama de l’escrache. Quelques militants se reposent sur le muret de la villa voisine. Certains chantent et somment Japie Hugo de sortir. Son portail, visible à droite du cliché, reste fermé. © Margaux de Barros

Figure 2: Panorama of the escrache. A few activists rest on the low wall of the neighbouring villa. Some of them sing and call for Japie Hugo to come out. His gate, visible on the right of the photograph, remains closed. © Margaux de Barros

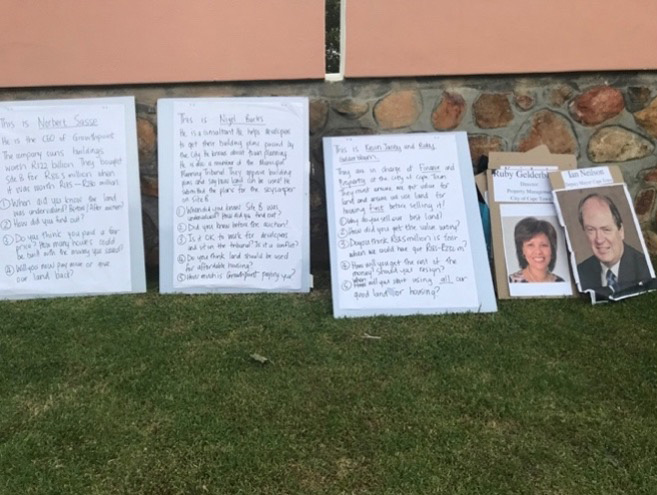

La présence des membres de RTC dénote dans un des quartiers les plus favorisés d’Afrique du Sud composé à 80 % de Blancs et à 4 % de Coloureds. Les militants sonnent à la porte et commencent à entonner les chants de RTC. Ils dansent et chantent au rythme de Asina luvalo et Senzeni Na. La banderole « Reclaim the City » est apposée sur le mur qui entoure le domicile et contre lequel sont également disposés plusieurs « panneaux de la honte » (figure 3).

The presence of RTC members in one of South Africa’s most privileged neighbourhoods, where 80% of the population is white and 4% coloured, is quite striking. Activists ring the doorbell and start singing RTC songs. They dance and sing to the rhythm of Asina luvalo and Senzeni Na. The “Reclaim the City” banner is placed on the wall surrounding the house, where a number of “panels of shame” are also displayed (figure 3).

Figure 3 : « Panneaux de la honte » retraçant la participation de représentants municipaux à la vente de Site B. © Margaux de Barros

Figure 3: “Panels of shame” recounting the involvement of municipal representatives in the sale of Site B © Margaux de Barros

Au bout d’une heure, la police arrive et interroge les leaders, avant de quitter les lieux (voir figure 4). Les militants restent sur place jusqu’à 18 heures, attendant que Japie Hugo accepte de répondre à leurs questions. En vain.

After an hour, the police arrive and question the leaders, before leaving the scene (see figure 4). The campaigners remained on site until 6 p.m., waiting for Japie Hugo to agree to answer their questions, in vain.

Figure 4 : Des militants discutent avec la police au sujet du respect du Gathering Regulation Act qui régit les rassemblements dans l’espace public © Matthew Wingfield

Figure 4: Activists argue with police about compliance with the Gathering Regulation Act, which governs gatherings in public spaces © Matthew Wingfield

L’escrache constitue un moyen de dénoncer la responsabilité des pouvoirs publics dans la distribution inégale des terres au Cap. Il traduit la nécessité de condamner publiquement les acteurs politiques, en dehors des arènes institutionnelles et judiciaires jugées défaillantes. Cette stratégie permet une inversion symbolique du stigmate. Ce sont les décideurs publics qui sont moralement condamnés pour leur action tandis que les victimes d’expulsions s’approprient temporairement l’espace de vie du décideur et entravent sa mobilité (celui-ci ne peut pas sortir ou, s’il le fait, doit se confronter aux manifestants).

The escrache is a way of drawing attention to the responsibility of the public authorities for the unequal distribution of land in Cape Town. It reflects the need to condemn political actors publicly, outside institutional and judicial arenas that are deemed to be failing. This strategy generates the possibility for a symbolic inversion of the stigma. It is the public decision-makers who are morally condemned for their action, while the victims of evictions temporarily appropriate the decision-maker’s living space and hamper his mobility (he cannot leave or, if he does, has to face the demonstrators).

Ces sorties qui se déroulent dans des quartiers blancs, privilégiés et très peu fréquentés par les enquêtés, visent également à éclairer leurs résidents sur les inégalités sociospatiales au sein de la ville. Lors de l’escrache, certains participants sont ébahis par les villas qui les entourent et mesurent ainsi le fossé social et économique qui les sépare de leurs élus.

These outings, which take place in white, privileged neighbourhoods where the respondents rarely go, also seek to shine the spotlight on socio-spatial inequalities within the city. During the escrache, some of the participants are amazed by the mansions that surround them and get a glimpse of the social and economic chasm that separates them from their elected representatives.

Conclusion

Conclusion

En composant avec les contraintes et les possibilités de l’espace urbain du Cap, RTC est parvenu à mettre en place un répertoire d’action territorial innovant, fondé principalement sur les occupations, qu’elles soient temporaires ou durables. L’inscription spatiale du mouvement remédie à la dispersion des habitants expulsés et permet l’émergence et le déploiement de la mobilisation. L’occupation d’un bâtiment public et les pratiques sociales quotidiennes qui s’y déroulent renforcent la cohésion du groupe, développent la culture politique des résidents du mouvement, et permettent leur mobilisation dans d’autres espaces de la ville. En combinant l’occupation durable à d’autres moyens d’action tels que l’usage du droit, les occupations temporaires et les escraches dans des quartiers gentrifiés et aisés, les militants bousculent l’ordre ségrégué du Cap. Ils déplacent les revendications de la périphérie vers le centre, rendent visibles les demandes de logement formulées par les classes populaires. Le combat des personnes expulsées devient une lutte pour le droit à la ville.

By tackling the constraints and possibilities of Cape Town’s urban space, RTC has succeeded in putting in place an innovative repertoire of territorial action, based primarily on occupations, whether temporary or long lasting. The spatial nature of the movement mitigates the dispersal of the evicted residents and allows mobilisation to emerge and spread. The occupation of a public building and the daily social practices that take place there reinforce group cohesion, develop the political culture of the movement’s residents, and enable them to mobilise in other areas of the city. By combining lasting occupation with other forms of pressure such as legal action, temporary occupations and escraches in gentrified and affluent neighbourhoods, the activists are able to shake the segregated order of Cape Town. They transpose the pressure of demands from the periphery to the centre, and give visibility to working-class housing claims. The struggle of those evicted becomes a struggle for the right to live in the city.

En 2022, l’ancien hôpital occupé accueille environ 1 200 personnes. En dépit de sa criminalisation, l’occupation est tolérée par la municipalité, sans doute parce qu’elle reste relativement invisible et éloignée des quartiers aisés et touristiques et qu’elle permet aux autorités de se soustraire à leur devoir de relogement. En juillet 2022, ses habitants organisent une marche appelée « Promenade de commémoration des parcelles et des promesses vides ». Se rendant sur quatre des onze sites sur lesquels la municipalité s’est engagée à construire des logements sociaux, les participants à cette marche interpellent les pouvoirs publics. L’inaction et le refus de ces derniers à mettre en œuvre des mesures significatives (encadrement des loyers, construction de logements sociaux) qui permettraient aux classes populaires de rester sur place illustrent plus généralement leur échec à rectifier la structure spatiale ségréguée de la ville.

By 2022, the former hospital was occupied by around 1,200 people. Despite being criminalised, the occupation is tolerated by the municipality, no doubt because it remains relatively low-profile and far from affluent and tourist areas, and allows the authorities to dodge their duty to rehouse people. In July 2022, the residents of the occupied site organised an “Empty Plots and Promises Commemoration Walking Tour” of Cape Town. Visiting four of the eleven sites on which the municipality had undertaken to build affordable housing, the marchers sought to call out the public authorities. Their inaction and refusal to implement significant measures (rent controls, construction of affordable housing) that would enable working-class residents to remain in the area illustrate, more generally, their failure to rectify the segregated spatial structure of the city.

Pour citer cet article

To quote this article

Barros Margaux (de), 2025, « L’usage stratégique du territoire dans la lutte contre la gentrification. Le cas de Reclaim the City à Woodstock (Le Cap) » [“The strategic use of land in the fight against gentrification. The case of Reclaim the City in Woodstock (Cape Town)”], Justice spatiale | Spatial Justice, 19 (http://www.jssj.org/article/lusage-strategique-du-territoire-dans-la-lutte-contre-la-gentrification-le-cas-de-reclaim-the-city-a-woodstock-le-cap/).

Barros Margaux (de), 2025, « L’usage stratégique du territoire dans la lutte contre la gentrification. Le cas de Reclaim the City à Woodstock (Le Cap) » [“The strategic use of land in the fight against gentrification. The case of Reclaim the City in Woodstock (Cape Town)”], Justice spatiale | Spatial Justice, 19 (http://www.jssj.org/article/lusage-strategique-du-territoire-dans-la-lutte-contre-la-gentrification-le-cas-de-reclaim-the-city-a-woodstock-le-cap/).

[2] Assignations raciales établies par le régime sud-africain de l’apartheid et qui continuent d’être utilisées par les pouvoirs publics sud-africains. Leur utilisation ne sert en aucun cas à approuver cette catégorisation, mais à examiner ses effets sur les agents sociaux.

[2] Racial categories established by the South African apartheid regime and which remain in use by South Africa’s public authorities. They are in no way used to reflect approval of these categories, but to examine their effects on social agents.

[4] Créée à la fin des années 2000, Ndifuna Ukwazi s’engage dans l’amélioration des conditions sanitaires dans les townships. Dès 2016, ses travailleurs se focalisent sur la question du logement au centre-ville. L’ONG est composée de onze militants professionnels sud-africains – dont deux chercheurs en urbanisme issus d’universités locales – engagés pour leurs compétences sociales, leur engagement antérieur et selon des critères raciaux et de genre de discrimination positive.

[4] The goal of Ndifuna Ukwazi, created at the end of 2000, was to improve health conditions in the townships. From 2016, its workers began to focus on the issue of housing in the city centre. The NGO was made up of eleven South African professional activists–including two urban planning researchers from local universities–hired for their social skills, their history of previous engagement and according to racial and gender criteria of positive discrimination.

[6] En 2012, une enquête de faisabilité́ conduite par la province du Cap-Occidental conclut à la possibilité d’y construire 270 unités de logement. La province procède pourtant à la vente du terrain en 2015.

[6] In 2012, a feasibility survey conducted by the Western Cape Province concluded that 270 housing units could be built there. However, the province sold the land in 2015.

[7] District Six est un quartier localisé entre le centre-ville du Cap et Woodstock qui a été décrété « zone blanche » par le Group Areas Act. La municipalité a organisé l’expulsion de plus de 60 000 personnes entre 1968 et 1970. Majoritairement classées comme « coloureds », ces dernières sont envoyées dans les townships des Cape Flats réservés aux coloureds.

[7] District Six is an area between Cape Town city centre and Woodstock that was declared a “white zone” under the Group Areas Act. The municipality organised the eviction of over 60,000 people between 1968 and 1970. Most of them were classified as “Coloureds” and sent to the townships in the Cape Flats reserved for people classified as coloured.