Introduction

Introduction

Dans un contexte de tension autour de la question du logement (Bouillon et al., 2019), d’hébergements en quantité insuffisante par rapport à la demande[1] et d’une crise de l’accueil des exilés (Lendaro et al., 2019), on observe la présence d’un nombre important de personnes à la rue à Paris. Ces personnes recourent à des solutions temporaires et souvent informelles pour habiter la ville et ces dernières font l’objet de différentes modalités de régulations (Froment-Meurice, 2016 ; Piva, 2021). L’évacuation d’un campement d’exilés à Saint-Denis, le 17 novembre 2020, en est un exemple significatif qui se termine par la dispersion violente de 500 à 1 000 personnes[2]. En réaction, certains des exilés et leurs soutiens décident d’occuper la place de la République, le 23 novembre 2020. La répression qu’ils subissent est largement médiatisée[3], imposant la question dans le débat public.

Against a background of tension around the issue of housing (Bouillon et al., 2019), a shortage of accommodation relative to demand,[1] and a crisis in the reception of exiles (Lendaro et al., 2019), the streets of Paris have become home to large numbers of rough sleepers. These homeless resort to temporary and often informal solutions to live in the city, solutions that are regulated in different ways (Froment-Meurice, 2016; Piva, 2021). The clearance of an exile camp in Saint-Denis on 17 November 2020 is a significant example, ending with the violent dispersal of between 500 and 1,000 people.[2] In response, on 23 November 2020, some of the exiles and their supporters decided to occupy Place de la République. The repression inflicted on them was widely reported in the media,[3] forcing the issue into the public arena.

C’est en réaction à cette situation que se forme le collectif Réquisitions, regroupant la Coordination 75 des sans-papiers (CSP75), le Droit au logement (DAL), Enfants d’Afghanistan et d’ailleurs (EAA), Paris d’exil (PE), Solidarité migrants Wilson (SMW), Utopia 56 (U56) et des représentants de deux collectifs de squatteurs. Il se constitue autour de l’application de la Loi de réquisition qui permet à l’État de saisir des bâtiments vacants pour y loger des personnes qui sont à la rue (ordonnance du 11 octobre 1945). Les actions du collectif sont préparées par des représentants de ces organisations dont une partie sont sans-papiers, anciens demandeurs d’asile, mal-logés, squatteurs ou hébergés dans des dispositifs d’urgence. Leur investissement militant dans des luttes collectives les distingue de la majorité des participants aux actions orientées sur la résolution à court terme de leurs situations de sans-abrisme ou de mal-logement. Entre décembre 2020 et septembre 2021, le collectif réalise 12 actions permettant l’hébergement de 4 600 personnes. Ces dernières sont considérées, pour la plupart, comme « indésirables » par les pouvoirs publics (Agier, 2010). Leur gestion se caractérise par une mise en errance forcée, notamment par les pratiques policières d’expulsion et d’évacuation de leurs lieux de vie.

The formation of the Réquisitions Collective was a response to this situation. It brought together a number of existing organisations–Coordination 75 des sans-papiers (CSP75), Droit au logement (DAL; Right to Housing), Enfants d’Afghanistan et d’ailleurs (EAA), Paris d’Exil (PE), Solidarité migrants Wilson (SMW), Utopia 56 (U56)–and representatives of two squatters’ collectives. It was built around the campaign for the application of the Requisition Act, a law that allows the state to seize vacant buildings to provide housing for homeless people (Ministerial Order of 11 October 1945). The Collective’s actions were planned by representatives of these organisations, some of them undocumented migrants, former asylum seekers, people living with poor housing conditions, squatters, or people in emergency accommodation. Their involvement in collective activism distinguishes them from most participants in housing-related protests, which usually focus on short-term solutions to homelessness or poor housing. Between December 2020 and September 2021, they ran 12 projects providing accommodation for 4,600 people, most of them considered “undesirable” by the authorities (Agier, 2010) and usually handled by forced displacement, i.e. police action to remove or evict them from their living spaces.

Les modalités de lutte du collectif, qui articulent l’appropriation d’espaces et de bâtiments publics avec des actions de visibilisation, s’inscrivent dans la continuité historique de mobilisations similaires et transnationales. En 2005, l’organisation non gouvernementale (ONG) Médecins du monde distribue des tentes aux personnes sans-abri dans Paris pour visibiliser leur situation, suivie par les Enfants de Don Quichotte un an plus tard (Bruneteaux, 2013). Plus généralement, l’installation de campements dans des lieux publics est commune à de nombreuses luttes. L’occupation de Tomkin Square à New York (Smith, 1989), de People’s Park à Berkeley (Mitchell, 1995), du parc Gezi à Istanbul (Erdi, 2019) ou encore des mouvements Occupy Wall Street, les Indignados, Nuit Debout (Pickerill et Krinsky, 2012) n’en constituent que quelques exemples. Le collectif Réquisitions mobilise également un répertoire d’actions hérité du DAL (Péchu, 2006) et du collectif Jeudi noir en occupant des bâtiments vacants. Ce mode d’action articule les luttes pour les droits au logement et à la ville des populations précarisées, comme à Rome (Grazioli et Caciagli, 2018) ou à Athènes (Kotronaki et al., 2018), et dont la diversité fait l’objet de mises en perspectives transnationales (Martínez López, 2018).

The collective’s methods of resistance–a mix of occupations of public spaces and buildings and awareness-raising campaigns–were consistent with a long tradition of similar mobilisations in different countries. In 2005, the non-governmental organisation (NGO) Médecins du monde distributed tents to homeless people in Paris to raise awareness of their situation, an action that was repeated a year later by Les Enfants de Don Quichotte (Bruneteaux, 2013). More generally, the establishment of camps in public places is a method that has been used in many such campaigns. The occupation of Tompkins Square in New York (Smith, 1989), People’s Park in Berkeley (Mitchell, 1995), Gezi Park in Istanbul (Erdi, 2019) and the Occupy Wall Street, Indignados and Nuit Debout movements (Pickerill and Krinsky, 2012) are just a few examples. The Réquisitions Collective also draws upon a repertoire of actions inherited from the DAL movement (Péchu, 2006) and the Jeudi Noir Collective by occupying vacant buildings. This type of approach is common to movements that support the housing and urban rights of vulnerable populations, for example in Rome (Grazioli and Caciagli, 2018) or Athens (Kotronaki et al., 2018). Its different forms have been explored in comparative international studies (Martínez López, 2018).

Nous fondons notre réflexion sur une enquête ethnographique d’un an au sein du collectif Réquisitions où nous avons réalisé des observations participantes lors des réunions et des actions nous permettant leur analyse multisituée ainsi que sur des entretiens semi-directifs menés auprès de membres de l’équipe organisatrice. Nous examinons comment les actions du collectif constituent un territoire de lutte pour le droit au logement à Paris, perturbant l’ordre sociospatial (Dikeç, 2002). Puis, nous étudions comment se négocie l’appropriation de ce territoire (Ripoll et Veschambre, 2005), et les modalités de son contrôle par les pouvoirs publics, notamment au prisme de la notion de démobilisation (Baby-Collin et al., 2021 ; Tilly et Tarrow, 2008) afin de saisir comment l’encadrement institutionnel des contestations participe à façonner leurs géographies. Dans ce raisonnement, le territoire désigne avant tout le produit de l’appropriation physique ou symbolique – même temporaire – d’un espace (Raffestin, 2019 [1980]), et est le produit d’un rapport de force.

Our analyses are based on a year-long ethnographic study within the Réquisitions Collective, where we conducted participant observations at meetings and campaigning events–which provided material for a multi-situated analysis–along with semi-structured interviews with members of the organising team. We examine how the Collective’s actions construct a territory of struggle for the right to a home in Paris, disrupting the socio-spatial order (Dikeç, 2002). We then look at how the occupation of this territory (Ripoll and Veschambre, 2005) is negotiated and the methods employed by the authorities to control it. In particular, we examine this control process through the notion of demobilisation (Baby-Collin et al., 2021; Tilly and Tarrow, 2008), in order to understand how the institutional framework of the protest actions helps to shape their geographies. According to this line of reasoning, territory is first and foremost the product of the physical or symbolic appropriation–however temporary–of a space (Raffestin, 2019 [1980]) and the outcome of power relations.

Cartographier un territoire de lutte pour le logement à Paris : un équilibre entre symboles et pragmatisme

Mapping a territory of struggle for housing in Paris: balancing the symbolic and the pragmatic

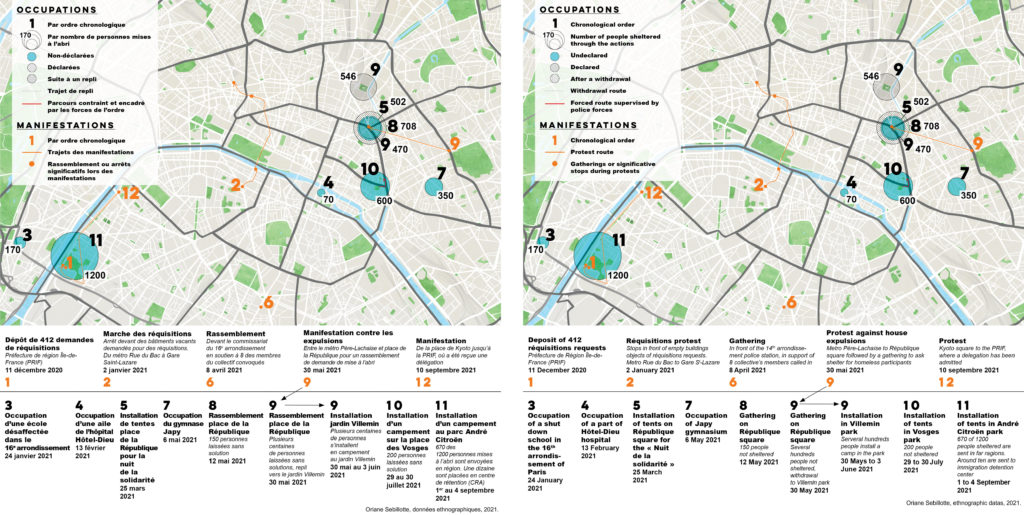

Les différents lieux investis par le collectif Réquisitions (figure 1) révèlent un territoire de lutte fragmenté, articulé entre la volonté de s’approprier des lieux symboliques afin de perturber la géographie sociospatiale de la ville et un impératif de sécurité des participants.

The different locations occupied by the Réquisitions Collective (figure 1) reveal a fragmented territory of struggle, a trade-off between the desire to take possession of symbolic locations in order to disrupt the socio-spatial geography of the city and the need to ensure the safety of participants.

Figure 1 : actions organisées par le collectif Réquisitions, 2020-2021. Réalisation : Oriane Sebillotte, données ethnographiques, 2021

Figure 1: Actions organised by the Réquisitions Collective, 2020-2021. Produced by: Oriane Sebillotte, ethnographic data, 2021

La première action non déclarée du collectif est l’occupation d’une école désaffectée dans le 16e arrondissement, le 24 janvier 2021. Elle intervient après le dépôt de 412 demandes de réquisitions à la préfecture de région d’Île-de-France (PRIF) et une marche dans Paris reliant plusieurs bâtiments proposés à la réquisition, deux démarches restées sans réponse. Par la suite, le collectif réalise sept occupations non déclarées d’espaces ou de bâtiments publics ou perçus comme tels[4], et trois manifestations déclarées. Chacune participe à matérialiser concrètement la lutte ainsi :

The Collective’s first, undeclared action was the occupation of a disused school in the 16th arrondissement on 24 January 2021. This followed the submission of 412 requisition applications to the Préfecture de région d’Île-de-France (PRIF) and a march through Paris linking several buildings proposed for requisition, neither of which approaches elicited any response. Subsequently, the collective carried out seven undeclared occupations of actual or apparent public spaces or buildings,[4] and organised three declared demonstrations. Each helped to give concrete expression to the struggle:

« Les lieux c’est important. […] Chaque fois qu’il y a le choix d’un lieu [nos camarades] nous disent : “ah, c’est un bon choix ! Ça, c’est vraiment symbolique, c’est bien choisi.” » (B., CSP75)

“Places are important. […] Every time there’s a choice of location [our comrades] tell us: ‘ah, that’s a good choice! That’s really symbolic, you chose well.’’’ (B., CSP75)

Ces actions cherchent alors à perturber « l’ordre des places », à dénoncer la financiarisation du bâti public, et à s’approprier l’espace tout en s’adaptant aux contraintes des lieux, des militants et à celles imposées par la régulation des espaces.

The aim of these occupations was to disrupt the “hierarchy of places”, to oppose the financialisation of public buildings by temporary seizure, while adapting to the constraints of the places and the participants, as well as those imposed by local spatial regulation.

Territoires de lutte projetés

Planned territories of resistance

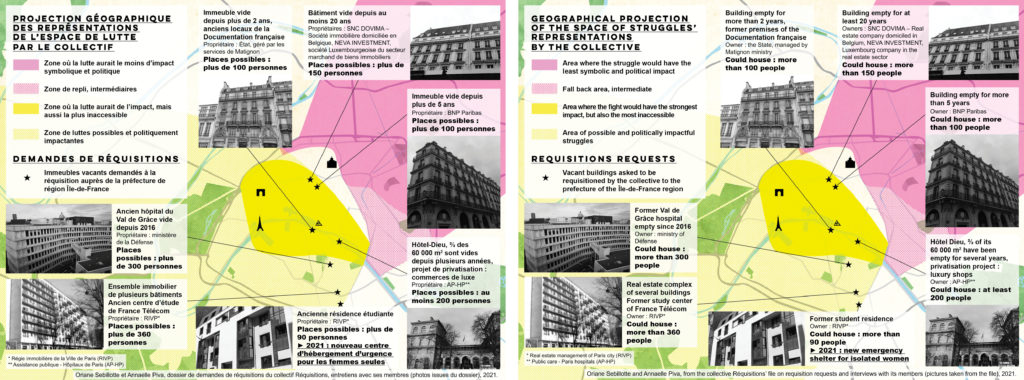

Pour les membres du collectif, quatre régions principales se distinguent dans Paris et déclinent des espaces de lutte souhaitables, mais difficiles à concrétiser ; des espaces possibles et politiquement intéressants ; des espaces intermédiaires qui peuvent offrir un repli et des espaces où les actions auraient peu d’impact politique (figure 2). Cette géographie fait écho à la cartographie de la répartition des richesses[5]. Les espaces de lutte souhaitables recoupent les lieux de pouvoirs tant politiques que financiers[6], tandis que les espaces de lutte offrant peu d’impact correspondent aux quartiers populaires de la capitale, également lieux d’errance des personnes à la rue. P. (SMW) souligne : « Le vrai enjeu pour moi c’est dans Paris », il précise : « enfin, dans les arrondissements les plus bourges. […] y a pas de raison que ce soit tout le temps les quartiers populaires qui prennent » résumant cette géographie de la lutte projetée sur le canevas parisien.

For the members of the Collective, Paris can be divided into four broad regions: areas where action would be desirable but difficult to undertake; areas where action is possible and politically valuable; intermediate areas that can be used as fallback spaces; and areas where action would have little political impact (figure 2). This geography corresponds to the map of wealth distribution.[5] The desirable areas for action comprise places of political and financial power,[6] while the areas of low impact are the capital’s working-class districts, which are also where rough sleepers tend to spend their time. As P. (SMW) points out: “The real challenge for me is in Paris: I mean, the most bourgeois districts. […] there’s no reason why it should always be the working-class neighbourhoods that take on the burden of poverty and homelessness, encapsulating aphy of the struggle projected onto the canvas of Paris.

Figure 2 : territoires de lutte projetés, au regard des demandes de réquisitions déposées à la préfecture. Réalisation : Oriane Sebillote et Annaelle Piva, dossier de demandes de réquisitions du collectif Réquisition, entretiens avec ses membres (photos issues du dossier), 2021

Figure 2: Projected areas of resistance, based on requisition requests submitted to the Prefecture. Produced by: Oriane Sebillote and Annaelle Piva, record of the Réquisition Collective’s requisition demands, interviews with its members (photos from the file), 2021

Chercher à perturber l’« ordre des places »

Seeking to disrupt the “hierarchy of places”

Pour « rendre visibles les invisibles »[7] auprès des pouvoirs publics, la géographie de la lutte s’articule autour du principe de transgression de l’ordre des places. Celui-ci correspond à la répartition sociospatiale des rôles et des fonctions dans la société, établie et maintenue par ce que Jacques Rancière qualifie de « police » (1995). Elle désigne ici l’ensemble des acteurs de la production urbaine néolibérale que sont les acteurs économiques, les pouvoirs publics, les forces de l’ordre et tous ceux qui instaurent et font respecter cette répartition à toutes les échelles et son orientation est prioritairement déterminée par les responsables politiques et les systèmes qui les placent en situation de responsabilité.

To “make the invisible visible”[7] to the authorities, the geography of the movement revolves around the principle of disrupting the hierarchy of places, the geographical pecking order. This order corresponds to the socio-spatial distribution of roles and functions in society, established and maintained by what Jacques Rancière describes as “police” (1995). Here, the term “police” refers to all the agents of neo-liberal urban production—i.e., economic agents, public authorities, the forces of law and order, and all those who establish and enforce this distribution at all levels – and its direction is primarily determined by the political leaders and the systems that place them in a position of responsibility.

Ainsi, le territoire de la lutte pour le droit au logement résulte de l’appropriation, même éphémère, de l’espace contre la « police ». Pour Jacques Rancière (1995), la « politique » qualifie les actions qui perturbent l’espace et l’interrogent au nom du principe d’égalité de tous avec tous. De la sorte, pour créer un territoire qui contrarie ce dernier, un lieu idéal d’action est un lieu dont l’appropriation, même temporaire, rompt avec des habitudes, crée un emballement médiatique et confronte les pouvoirs publics afin d’instaurer un rapport de force.

In this sense, the territory of the struggle for the right to a home arises from the seizure of space, however ephemerally, in conflict with the “police’”. For Jacques Rancière (1995), “politics” refers to actions that disrupt the spatial order and challenge it in the name of the principle of human equality. In consequence, in order to create a territory that counteracts this, an ideal locus for action is one whose appropriation–albeit temporary–constitutes a break with the norm, generates media interest and confronts the authorities in order to alter the balance of power.

Il s’agit de se rendre visibles dans des lieux qui sont éloignés des réalités sociales propres aux précarités résidentielles, administratives ou économiques, comme le dit M. (U56) : « pour moi y a deux Paris : y a le Paris des cartes postales et le “vrai” Paris […] Mettre Paris “en vrai” – c’est les gens à la rue – […] dans le Paris des cartes postales ». Cette confrontation contient également une dimension relationnelle. Il s’agit de s’exposer aux regards et de rappeler aux plus nantis l’existence des participants aux actions.

The idea is to become visible in places that are far removed from the social realities of residential, administrative or economic vulnerabilities, as M. (U56) puts it: “For me, there are two Parises: postcard Paris and the ‘real’ Paris […] Putting the ‘real’ Paris—i.e., rough sleepers–[…] into postcard Paris.” This confrontation also has a relational dimension. It is about raising public attention and reminding the rich of the existence of the people at the heart of the protest.

Transgresser l’ordre des places dans la ville repose aussi sur la médiatisation des actions : « place des Vosges […] les médias ont réagi, les touristes ont réagi, et du coup les pouvoirs publics ont réagi » (P., SMW). Ce lieu devient un outil de communication, « c’est un lieu hyper symbolique, c’est un des lieux les plus friqués de Paris, et tu vas te poser, tu fais des photos superbes » (P. SMW). Cet esthétisme montre implicitement que tous les lieux ne se valent pas et que les plus transgressifs vont répondre à l’impératif de proposer des images qui interpellent : « tu vois bien dans la presse, on a du mal à les mobiliser […] là tu leur offres un truc qu’ils prennent par un bout inhabituel ». La « spectacularisation » des actions devient alors « une condition structurelle » de ces dernières (Ripoll, 2008, p. 88) dans un contexte où les tentes ont normalisé le sans-abrisme dans le paysage urbain (Zeneidi-Henry, 2010).

Transgressing the hierarchy of places in the city also relies on media coverage: “Place des Vosges […] the media reacted, tourists reacted, and as a result the authorities reacted” (P., SMW). The square became a tool of communication, “it’s a hyper-symbolic site, one of the poshest places in Paris, and you go and occupy it, and you take some great photos” (P., SMW). This aestheticism implicitly shows that not all places are equal and that real iconoclasts will rise to the imperative of producing images that challenge people: “As you can see in the press, it’s hard to get them on board […] but here you’re offering them an unusual angle on things.” “Spectacularisation” thus becomes “a structural condition” of the protest events (Ripoll, 2008, p. 88) in circumstances where tents have normalised homelessness in the urban landscape (Zeneidi-Henry, 2010).

Pour autant, le choix de certains des lieux répond en priorité au besoin immédiat d’hébergement des participants au détriment de la transgression. C’est le cas de la place de la République qui représente pour le collectif un lieu sanctuarisé par la répression du 23 novembre 2021. P. (SMW) soulève néanmoins la difficulté à se faire entendre dans un espace implicitement dédié aux luttes « c’est une espèce de maelstrom. […] Pour arriver à te faire entendre là-dedans, c’est quand même pas évident ».

However, some of the venues were chosen primarily to meet the participants’ immediate need for accommodation, rather than for transgressive purposes. This was the case with Place de la République, which for the Collective came to be a sanctuary space following the crackdown of 23 November 2021. P. (SMW) nevertheless emphasised the difficulty of getting listened to in a space implicitly dedicated to struggle. “It’s a kind of maelstrom. […] Ultimately, it’s not easy to make your voice heard in there.”

Certains lieux sont choisis dans la contrainte, et constituent des espaces de repli, « on s’est fait virer ce matin [après une action], il fallait juste un endroit de repli rapide […] t’as quand même plus symbolique qu’un lieu de repli ! » (M., U56). Ce sont des espaces familiers pour les associations du collectif qui y interviennent au quotidien auprès des personnes à la rue. Le 30 mai 2021, à la suite du rassemblement place de la République, environ 500 personnes dispersées par les forces de police se replient dans le square Villemin, parfois surnommé « Little Kabul », en raison de son occupation régulière par des demandeurs d’asile afghans (Emmaüs Solidarité et France terre d’asile, 2011). L’installation répétée de campements dans ce lieu, ou son usage pour des actions militantes, en fait un espace peu transgressif. M. (U56) identifie comme lieux de repli possible des quartiers « délaissés par les […] pouvoirs publics. Là, ils viendront pas te chercher » (M., U56). C’est un espace qui, telle la place de la République, ne vient pas perturber l’ordre des places en renvoyant aux hiérarchies sociales qui traversent ces quartiers sans les remettre en question (Dikeç 2002), ainsi que le rappelle F. (DAL) :

Some locations were chosen under duress and used as fallback spaces: “we got chased out this morning [after a protest operation], we just needed a quick place to fall back to […] surely you’ve got something more symbolic than a fallback location!” (M., U56). These are areas that are familiar to the Collective’s member organisations, which work there with rough sleepers on a daily basis. On 30 May 2021, following the rally at Place de la République, around 500 people were dispersed by the police and withdrew to Square Villemin, sometimes nicknamed “Little Kabul” because of its frequent occupation by Afghan asylum seekers (Emmaüs Solidarité and France terre d’asile, 2011). The frequent presence of homeless camps in this area, together with its use for demonstrations, makes it a relatively non-transgressive space. M. (U56) identifies neighbourhoods that have been “abandoned by the […] authorities” as possible fallback areas. “They won’t come looking for you there” (M., U56). They are spaces which, like Place de la République, do not disrupt the hierarchy of places by challenging the social pecking orders that pervade these neighbourhoods without challenging them (Dikeç, 2002), as F. (DAL) reminds us:

« Les pauvres sont chez les pauvres. Ils s’en foutent […]. Même pour les gens c’est une habitude en fait… ils sont pas très étonnés. » (F., DAL)

“The poor live with the poor. They don’t give a damn […]. In fact, for some people it’s even an everyday reality… They don’t find it very surprising.” (F., DAL)

Enfin, certaines localisations des actions traduisent la volonté d’établir un rapport plus frontal avec les pouvoirs publics chargés de l’hébergement et du logement. L’installation d’un campement dans le parc André Citroën, face à la PRIF, instaure une proximité spatiale entre les demandeurs de logement et l’administration : « le parc Citroën, [c’est] à côté de [la PRIF]. Voilà le sens du défi […] Parce que finalement c’est un rapport de force. » (B., CSP75). Cette proximité traduit également la volonté du collectif de dialoguer directement avec les autorités.

Lastly, the locations of some of the protests reflect the desire to establish a more head-to-head relationship with the authorities responsible for shelter and housing. The formation of a camp in André Citroën Park, opposite the PRIF, created a spatial proximity between housing applicants and the housing administration: “Parc Citroën is next to the PRIF. That’s the point of the challenge […] Because in the end it’s about a balance of power.” (B., CSP75). This proximity also reflects the Collective’s desire to enter into direct dialogue with the authorities.

Toutefois, le collectif Réquisitions cherche un équilibre entre la volonté d’interpeller et celle de protéger les participants aux actions, notamment les plus précaires administrativement comme les sans-papiers. Cet aspect plus pragmatique se traduit par des choix de lieux qui révèlent une connaissance fine de l’administration des espaces de la ville. La préfecture ne peut intervenir dans certains lieux du domaine municipal que lorsque la mairie en fait la demande, tel que l’énonce M. (U56) :

However, the Réquisitions Collective wished to strike a balance between the desire to challenge and the desire to protect the people taking part in their protests, particularly those with the most precarious administrative status, such as undocumented migrants. This more pragmatic element was reflected in the choice of locations, which reveals a detailed knowledge of the administration of the city’s spaces. The prefecture can only intervene in certain parts of the municipal domain if requested by the mayor, as noted by M. (U56):

« C’est pas pour rien qu’on choisissait des lieux “mairie” le plus possible. C’est que ça t’assurait un minimum de protection politique et que… tu joues un peu sur l’opposition mairie-préf. » (M., U56)

“It’s no accident that we chose ‘municipal’ locations as much as possible. It’s because it gave you a degree of political protection and… you play a bit on the tensions between the mayor and the prefecture.” (M., U56)

Les actions s’inscrivent dans des espaces ou des bâtiments publics. Il s’agit d’interpeller en profitant de la plus grande accessibilité et visibilité des lieux tout en contredisant les mécanismes de filtrage social et d’exclusion des plus pauvres qui les caractérisent (Froment-Meurice, 2016). Outre le projet de perturber géographiquement l’ordre des places pour visibiliser et chercher à nouer un dialogue avec les pouvoirs publics, le territoire de lutte pour le logement met en tension la valeur d’échange et la valeur d’usage des bâtiments vacants (Brenner et al., 2012).

The protest actions take place in spaces or buildings that are public. The aim is to make an impact by taking advantage of the greater accessibility and visibility of these places, while at the same time counteracting the mechanisms of social filtering and exclusion of the poorest populations that characterise them (Froment-Meurice, 2016). In addition to pursuing the objective of geographically disrupting the hierarchy of places in order to raise awareness and to try to establish a dialogue with the authorities, the territory of the housing struggle sets up a tension between the exchange value and the use value of empty buildings (Brenner et al., 2012).

Lutter pour le droit d’habiter la ville face à la financiarisation du bâti

Fighting for the right to live in the city: the financialisation of the built environment

La dénonciation de la vacance de bâtiments habitables et la demande de leur réquisition comme moyen d’accéder au « logement pour tous » sont au cœur des actions du collectif Réquisitions. Lors de la marche du 2 janvier 2021 (figure 1), des bâtiments vacants appartenant à de grands groupes financiers, à l’État ou à la mairie sont alors désignés par le cortège qui s’arrête devant et par des prises de paroles. Pour P. (SMW), « on pointe du doigt en disant “ça, c’est libre et ça appartient à telle institution et pourquoi y a pas des gens dedans ?” ». En plus de rendre publique la disponibilité de ces espaces, en prendre possession est un moyen de rééquilibrer des rapports sociospatiaux inégalitaires et de faire primer le droit au logement sur la financiarisation du bâti : « [il y a] des gens qui sont sans logis, alors [il faut] annexer des logements vides, […] annexer des richesses là où il y a vraiment un vide… » (B., CSP75). Cette lecture donne sens à l’occupation d’une aile de l’hôpital Hôtel-Dieu, vacante depuis des années et vendue par l’Assistance publique – Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP) pour être transformée en galerie commerciale. Alors que ce lieu incarne l’accueil inconditionnel, historiquement et dans le discours des membres du collectif, son accaparement par le marché de la valorisation immobilière met en exergue la marchandisation du cœur de la capitale. B. (CSP75) explique combien la réquisition s’oppose à ces mouvements de commodification (Harvey, 2003), et que son application nécessiterait de privilégier la valeur d’usage sur la valeur d’échange :

Central to the Réquisitions Collective’s priorities were its opposition to habitable buildings lying empty and its demand for requisition to be used as an instrument for providing access to “homes for everyone”. During the march on 2 January 2021 (figure 1), the procession and speakers at the event drew attention to vacant buildings belonging to major financial groups, the state or the city of Paris, by stopping in front of them. For P. (SMW), “we point at them and say, ‘this is empty and belongs to such and such an institution and why aren’t there people in it?’” As well as publicising the availability of these spaces, taking possession of them is a way to rebalance unequal socio-spatial relations and to ensure that the right to a home takes precedence over the financialisation of the built environment: “[There are] people who have nowhere to live, so [we need to] annex empty dwellings, […] annex wealth where there is a real vacuum…” (B., CSP75). This perspective explains the occupation of a wing of the Hôtel-Dieu hospital that had lain empty for years and had been sold by the Assistance publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP) for conversion into a shopping arcade. While historically and as recalled in the speeches of the Collective, this building represented the embodiment of unconditional hospitality, its capture by property developers highlighted the commodification of the heart of the capital. B. (CSP75) explained the extent to which requisition represents a pushback against these commodification processes (Harvey, 2003), and how its application would require use value to be prioritised over exchange value:

« On va parler de réquisition en France, ça fait peur. […] C’est une loi qui gêne, si on va l’appliquer. Mais qui, qui possède les grands bâtiments à Paris ? C’est pour des banques […] Ça fait peur, ça va rentrer dans des trop gros problèmes. La spéculation c’est des problèmes et pour eux [l’État], ils veulent pas rentrer dans de tels problèmes. » (B., CSP75)

“There’s going to be talk about requisitioning in France, and that frightens people. […] It’s an inconvenient law, if it ever gets enforced. But who owns the big buildings in Paris? It’s for banks […] It’s scary, it’s going to raise some seriously big issues. Speculation is a problem and they [the government] don’t want to get involved in issues like that.” (B., CSP75)

Les pouvoirs publics – tant l’État que la municipalité de Paris – sont donc également soumis aux pressions du marché. À ce titre, un des bâtiments identifiés par le collectif (figure 2) a été réquisitionné à la demande de la mairie de Paris afin d’en faire un centre d’hébergement pour femmes. À l’inverse, l’ancien édifice de la Documentation française (une maison d’édition d’État), dont la réquisition a été sollicitée par la mairie, ne l’a pas été :

So the authorities–both central government and the City of Paris–are also subject to market pressures. One of the buildings identified by the Collective (figure 2) was requisitioned at the request of the City of Paris to be used as a women’s shelter. On the other hand, the former Documentation française (a State publishing house) building, which the mayor wanted to requisition, was not:

« Comment on peut avoir ça ? […] Ça touche à quelque chose de sensible, là où il y a de l’argent, là où il y a le pouvoir, là où il y a beaucoup de choses qui pèsent, et ça gêne. » (B., CSP75)

“How can that happen? […] It touches a raw nerve, where there’s money, where there’s power, where there’s a lot at stake, and people don’t like it.” (B., CSP75)

L’abandon de ce second projet révèle l’opposition entre les espaces accessibles (le XIIIe, une ancienne résidence étudiante à l’architecture banale) et ceux qui sont inatteignables (l’ancienne Documentation française, un bel immeuble dans les quartiers riches de la ville) (figure 2), explicitant l’idée d’une « marchandisation du monde » (Aguilera, 2021, p. 8) qui l’emporte sur le droit d’habiter.

The abandonment of this second plan reveals the difference between accessible spaces (the 13th arrondissement, a former student residence with little architectural merit) and spaces that are off-limits (the former Documentation française, a beautiful building in a rich part of the city) (figure 2). It gives explicit expression to the idea of the “commodification of the world” (Aguilera, 2021, p. 8), which takes precedence over the right to a roof.

Appropriation spatiale : faire territoire par la lutte

Spatial appropriation: making territory through struggle

L’enjeu de visibilité est lié au choix des lieux, mais aussi aux types d’actions et au sens qui leur est donné par les participants. L’espace permet une mise en spectacle de l’occupation, grâce au décor fourni par l’environnement, par le placement des participants et le déroulement de l’action. Leurs formes s’hybrident, entre « actions coup de poing » M. (U56) et revendications pratiques et pragmatiques, où la demande d’un abri se matérialise par son installation ou par son occupation. Cette appropriation collective (Ripoll et Veschambre, 2005) devient politique en détournant les usages de l’espace pensés par l’État (Aguilera, 2021).

The issue of visibility is linked to the choice of location, but also to the forms of protest and the meaning assigned to it by the participants. The location choice raises the profile of the occupation, because of the nature of the surroundings, the positioning of the participants and the way the action unfolds. The campaigns take hybrid forms, a mix of “high-impact operations” (M., U56) and practical, pragmatic demands, where the call for shelter coincides with the appropriation or occupation of a living space. This collective appropriation (Ripoll and Veschambre, 2005) becomes political by diverting the space away from the uses allocated by the state (Aguilera, 2021).

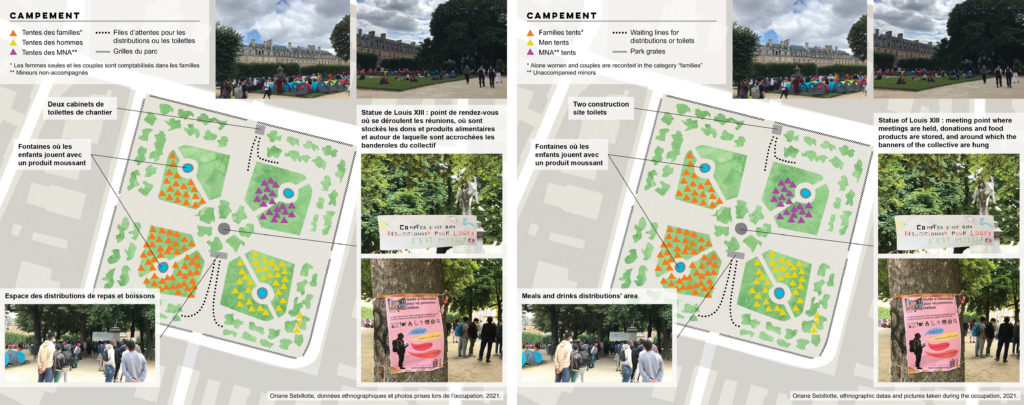

Bien que les actions diffèrent les unes des autres, leur organisation se ritualise partiellement : des aspects logistiques (masques et gel hydroalcoolique, tables et repas…), des activités festives (fanfare, jeux…) ou des éléments de revendication (tracts, banderoles…) marquent ainsi la prise de possession des lieux. L’organisation quotidienne dans le lieu en redéfinit la fonction : le socle d’une statue devient une plateforme pour les prises de paroles ; un endroit sous le couvert des arbres : un lieu de distribution des repas ; un espace ouvert : une piste de jeux (figure 3). Se mêlent ainsi des usages et des installations qui sont autant de moyens de s’approprier physiquement et matériellement l’espace, de l’habiter. Cette appropriation du territoire constitue la démonstration de la capacité d’autogestion et d’action des participants qui cherchent à proposer une autre façon de penser l’hébergement pratiqué par l’État :

Although the operations differed, they took on a partially ritual character: logistics arrangements (masks and hand sanitiser, tables and meals…), festive activities (brass bands, games…) or protest materials (leaflets, banners…) marked the takeover of the site. Day-to-day arrangements in the space redefine its function: the base of a statue becomes a speaking platform; a place under the trees becomes a meal distribution spot; an open space becomes a playground (figure 3). This mixing of uses and materials is a way of physically and materially appropriating the space, of inhabiting it. This territorial appropriation demonstrates the participants’ capacity to organise and act for themselves in their quest to promote a different way of thinking about state-provided housing:

« Les gens, ils ont pas besoin d’avoir plein de règles […]. On est quand même aussi sur l’autogestion […]. On sait très bien que le 115, les structures d’hébergement, c’est strict quand même. C’est une prison hein… » (F., DAL)

“People don’t need tons of rules […]. Ultimately, we can organise ourselves […]. After all, we know full well that the 115, the housing structures, are strict. It’s a kind of prison, isn’t it?” (F., DAL)

Figure 3 : campement installé par le collectif place des Vosges, le 29 juillet 2021. Réalisation : Oriane Sebillotte, données ethnographiques et photos prise lors de l’occupation, 2021

Figure 3: Camp set up by the collective on Place des Vosges, 29 July 2021. Produced by: Oriane Sebillotte, ethnographic data and photos taken during the occupation, 2021

Les personnes mises en errance (les demandeurs d’asile, les sans-papiers, les pauvres) font acte de réappropriation des espaces et d’une citoyenneté insurgée (Isin, 2002, p. 273) en revendiquant un droit à la ville « de fait » (Morange et Spire, 2017). La durée de l’installation dans le lieu amplifie son appropriation et son autogestion. Les membres du collectif qui organisent la mobilisation se reposent de plus en plus sur les participants pour aménager la vie du lieu tout en devant pallier les défis logistiques que représente l’occupation. Toutefois, l’appropriation des lieux dans le cadre des actions ne présente pas les conditions nécessaires à la création d’un « espace public subalterne » soit un lieu qui offre « des arènes discursives parallèles dans lesquelles les membres des groupes sociaux subordonnés élaborent et diffusent des contre-discours, ce qui leur permet de fournir leur propre interprétation de leurs identités, de leurs intérêts et de leurs besoins » (Fraser, 2005, p. 126). La diversité des profils administratifs et des attentes des participants couplée à la brièveté de l’occupation (de plusieurs heures à quelques jours) ne permettent pas à cette parole politique d’émerger comme cela a été le cas dans la politisation des participants aux actions des Enfants de Don Quichotte (Bruneteaux, 2013).

Homeless people (asylum seekers, undocumented migrants, the poor) reclaim spaces and an insurgent citizenship (Isin, 2002, p. 273) by demanding a “de facto” right to the city (Morange and Spire, 2017). The length of time you spend at the protest site amplifies the scale of appropriation and self-management. The members of the Collective who organise the mobilisation increasingly come to rely on the participants to manage the life of the place, while at the same time having to handle the logistical challenges posed by the operation. However, occupation for purposes of protest does not generate the conditions needed to create a “subaltern public space”, i.e. a place that offers “parallel discursive arenas in which members of subordinate social groups develop and disseminate counter-discourses, enabling them to express their own interpretation of their identities, interests and needs” (Fraser, 2005, p. 126). Because of the diversity of the participants’ administrative profiles and needs, coupled with the brevity of the occupation (from a few hours to a few days), the conditions were not right for this political discourse to emerge, as it did in the politicisation of the participants in the operations staged by Les Enfants de Don Quichotte (Bruneteaux, 2013).

Cette appropriation, pensée initialement pour la demande de logement et l’application de la Loi de réquisition est très rapidement réorientée vers l’obtention d’un hébergement dans les interactions avec les pouvoirs publics. Malgré la politisation de leurs membres-organisateurs, ses actions se reconfigurent en plateformes pour des mises à l’abri, esquissant les contours d’une démobilisation.

This kind of temporary occupation, initially intended to underpin demands for housing and for the application of the Requisition Act, very quickly shifted in its intent towards the effort to obtain accommodation in interaction with the authorities. Despite the politicisation of the Collective members-organisers, these operations became platforms for obtaining accommodation, thereby initiating the first steps in a process of demobilisation.

Régulation, normalisation, démobilisation

Regulation, standardisation, demobilisation

La trajectoire des actions du collectif Réquisitions vue au prisme de ses interactions avec les pouvoirs publics montre dans une certaine mesure la démobilisation du mouvement. Ce processus de dépolitisation collectif se distingue de la dimension individuelle du désengagement (Tejel-Gorgas, 2013). Il ne présuppose pas nécessairement l’intentionnalité des acteurs impliqués, mais laisse percevoir une régulation et une normalisation qui fait baisser le niveau de conflictualité progressive (Bacqué, 2005). Il passe par des relations de proximité entre militants et représentants des pouvoirs publics et par des tentatives concrètes de certains acteurs pour empêcher la lutte par la répression. Il se concrétise également dans la mise en place d’une réponse routinière à l’urgence du sans-abrisme – les mises à l’abri – qui participe à une normalisation des actions, modifiant les positionnements et les pratiques des acteurs (Baby-Collin et al., 2021 ; Tilly et Tarrow, 2008). En effet, les participants, militants lors d’une action, sont assignés par les pouvoirs publics au rôle d’opérateurs ou de bénéficiaires, entraînant une restructuration progressive de la forme limitant la portée des revendications.

The trajectory of the actions organised by the Réquisitions Collective, seen through the prism of its interactions with the authorities, to some extent reveals the demobilisation of the movement. This collective depoliticisation is distinct from political engagement, which is an individual process (Tejel-Gorgas, 2013). It does not necessarily presuppose intentionality in the people concerned, but suggests a trajectory of regulation and standardisation that gradually lowers the tempo of conflictuality (Bacqué, 2005). It entails the development of close relations between activists and public representatives and practical attempts by certain players to inhibit struggle by means of repression. It is also accompanied by the emergence of a routine dimension in the response to the emergency of homelessness—i.e., the provision of shelter – which contributes to the standardisation of the protest operations and a change in the positions and practices of those involved (Baby-Collin et al., 2021; Tilly and Tarrow, 2008). Indeed, having started out as activists in the staging of a protest operation, the participants come to be assigned a role as agents or beneficiaries by the authorities, which gradually reshapes the form of the process and hence limits the scope of the demands.

Différencier les acteurs, un outil de négociation et un moyen de contrôle

Differentiating between actors: a negotiating tool and a means of control

Le collectif interpelle par ses actions l’État et la mairie de Paris. Le premier est représenté sur le terrain par les acteurs du contrôle (police), de l’hébergement (la direction régionale et interdépartementale de l’hébergement et du logement [DRIHL]), et de l’asile (l’association France terre d’asile [FTDA]), mandatés pour orienter les participants aux actions. La mairie, échelon politique perçu comme plus accessible, est représentée par son unité d’assistance aux sans-abri (UASA). Réquisitions interagit principalement avec des acteurs opérationnels, et plus rarement avec les responsables institutionnels lors des rencontres des délégations et par l’intermédiaire des communiqués et des déclarations dans les médias.

Through its actions, the Collective posed a challenge to the state and the municipality. The former was represented in situ by the actors responsible for control (police), for accommodation (the regional and interdepartmental accommodation and housing directorate [DRIHL]), and for asylum (the France terre d’asile [FTDA] organisation), which were officially tasked with offering guidance to the protesters. The municipal council, which was perceived as a more accessible political tier, was represented by its Unité d’assistance aux sans-abri (UASA; Homeless Assistance Unit). Réquisitions interacted mainly with ground-level operatives–and more rarely with institutional officials–at delegation meetings and through press releases and media statements.

Les membres du collectif constatent que celui-ci n’est pas un interlocuteur privilégié par les pouvoirs publics. Ces derniers favorisent les interactions prévisibles et balisées par une certaine routinisation qui atténue la dimension revendicative des rencontres, « les revendications sont les mêmes depuis longtemps pour le DAL. Donc tout ça, c’est cadré » (F., DAL). M. (U56) explique qu’« [à la mairie], ils avaient essayé de limiter la délégation parce qu’ils essayaient justement de garder le lien avec des organisations précises plutôt que [de] reconnaître le collectif Réquisitions en tant que tel ». Cette volonté apparaît comme un moyen de contourner la revendication politique commune en privilégiant les demandes et les relations de proximité préexistantes.

The Collective’s members were aware that it was perceived by the authorities as their preferred interlocutor. They favoured predictable interactions, marked by a certain routine that would reduce the conflictual dimension of the meetings: “for the DAL, the demands have been the same for a long time. So it’s all business as usual” (F., DAL). M. (U56) explained that “[at city hall], they had tried to restrict delegation precisely because they wanted to maintain the link with specific organisations rather than to recognise the Réquisitions Collective as such”. This preference seemed to be a way to circumvent shared political demands by giving precedence to pre-existing local demands and relationships.

Cette différenciation est perçue par les membres du collectif comme une manière de les diviser en les distinguant dans les négociations. La gestion policière des actions (Della Porta et Reiter, 1998) induit une prise de risque plus grande pour les participants sans-papiers. Ainsi, B., de la CSP75, analyse le placement en rétention de dix personnes sans-papiers et les obligations de quitter le territoire français (OQTF) reçues après l’évacuation du parc André Citroën comme une tentative de déstabilisation : « l’État, il utilise cette situation administrative fragile pour qu’on n’existe plus dans ce collectif […] pour essayer de diviser ».

This differentiation was perceived by the members of the Collective as a way to divide them by sidelining them in negotiations. The policing of the protest events (Della Porta and Reiter, 1998) had the effect of increasing the risks to undocumented participants. For example, B., from the CSP75, analysed the detention of ten undocumented migrants and the obligations de quitter le territoire français (OQTF; official national expulsion order) issued after the evacuation of André Citroën Park as an attempt to subvert the movement: “The state uses this insecure administrative status to ensure that we cease to be a part of this Collective […] to try and divide us.”

Réciproquement, les membres du collectif différencient les pouvoirs publics. K. (U56) explique qu’« on peut pas mettre sur le même pied d’égalité l’État, le gouvernement, la préfecture d’Île-de-France et la mairie de Paris » et que ce sont les différences relationnelles entre les agents de terrain et les décisionnaires qui nuancent leur perception des pouvoirs publics. M. (U56) relate que FTDA est une association qui obéit à la PRIF et se voit donc limitée,

In turn, the Collective’s members made their own distinctions between the authorities. K. (U56) explained that “you can’t put the state, the government, the Île-de-France prefecture and the City of Paris on the same footing” and that it is the differences in the relations between the people on the ground and decision-makers that cloud their perception of the authorities. M. (U56) explained that FTDA as an organisation was answerable to the PRIF and was therefore restricted,

« mais individuellement, dans la maraude, y a des gens […] qui vont remuer tout ce qu’ils peuvent à leur échelle pour faire avancer la situation. Mais quand ils viennent aux actions, ils sont pas décisionnaires, c’est pas eux qui font l’ouverture de place […] et c’est pas eux qui vont changer la politique migratoire. » (M., U56)

“but individually, among the street level support workers, there are people […] who will do everything they can at their level to help the situation. But when it comes to the protest campaigns, they’re not the decision-makers, they’re not the ones who open up the squares […] and they’re not the ones who are going to change migration policy.” (M., U56).

Toujours selon lui, cette proximité n’empêche pas la politisation de la lutte :

Again according to him, the closeness of these relations did not prevent the fight becoming politicised:

« On peut être radical et rationnel, […] faut aussi se rendre compte de ce qui est de la responsabilité de la mairie et de ce qui est de la responsabilité de l’État, […] il y a des fois, juste légalement, c’est la responsabilité de l’État. » (M., U56)

“You can be radical and rational, […] you also have to realise what is the responsibility of the city and what is the responsibility of the state, […] sometimes, just legally, it’s the responsibility of the state.” (M., U56)

Les relations de proximité avec les acteurs de terrain, en contraste avec les relations d’opposition aux acteurs décisionnaires, nuancent des grilles de lectures militantes « voir comment ça se passe de leur côté, ça m’a aussi fait prendre conscience de leurs enjeux, de leurs contraintes. Ça a nuancé un peu la façon dont je voyais leur travail » (O., PE).

The close relationship with the support workers on the street, in contrast to the adversarial relationship with the decision-makers, added nuance to the views of the activists: “Seeing how things work on their side also made me aware of their challenges and constraints. It somewhat changed the way I saw the work they do” (O., PE).

Les mises à l’abri : effacer la question du logement, effacer la lutte

Shelters: erasing the housing issue, erasing the struggle

Les relations avec des acteurs mandatés pour trouver des solutions inscrites dans le registre de l’urgence (Gardella, 2014) déterminent l’issue de l’action, B. (CSP75) analyse ainsi :

The relations with the people tasked with finding emergency solutions (Gardella, 2014) was critical to the outcome of the protest movements. B. (CSP75) describes the situation as follows:

« ils choisissent la chose la plus facile : l’hébergement. […] Cette urgence qui se crée par l’action, elle crée aussi l’urgence de la mise à l’abri […] je crois que jamais ils ont pensé à des logements, bien que nous on parle d’un logement, un toit pour tous. » (B., CSP75)

“They choose the easiest thing: accommodation. […] The protests generated a sense of emergency, and the response was to provide emergency shelter […] I don’t think they’d ever thought about housing, even though we are always talking about housing, giving everyone a roof over their heads”. (B., CSP75)

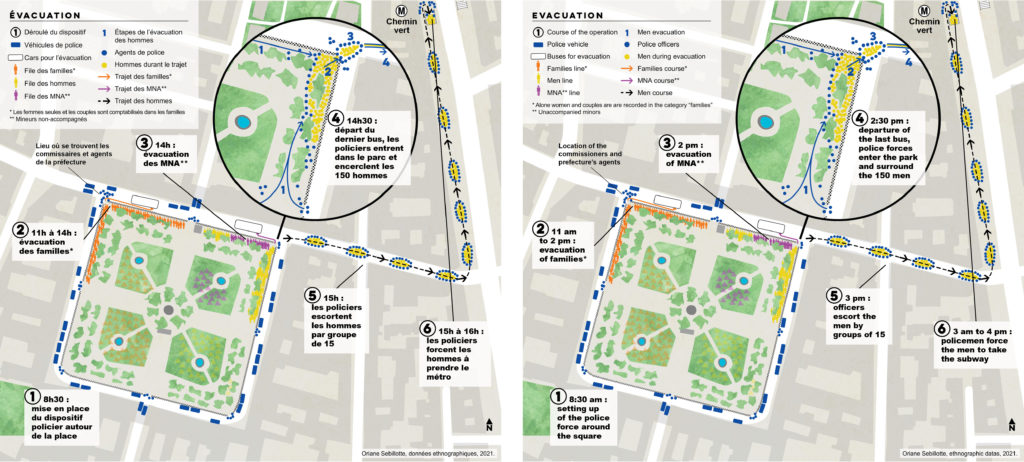

Figure 4 : évacuation du campement de la place des Vosges, le 30 juillet 2021. Réalisation : Oriane Sebillotte, données ethnographiques, 2021

Figure 4: evacuation of the camp on Place des Vosges, 30 July 2021. Produced by: Oriane Sebillotte, ethnographic data, 2021

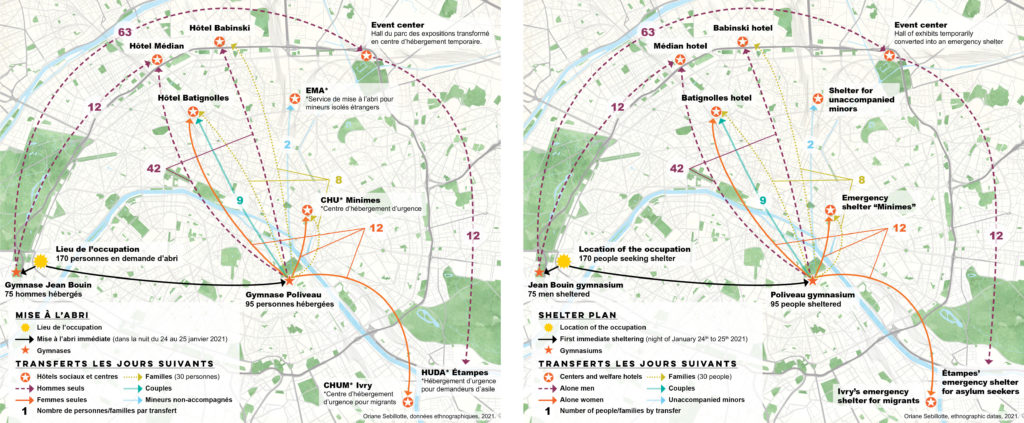

Dans le cadre des actions du collectif Réquisitions, une mise à l’abri commence par le déploiement d’un dispositif policier (figurés bleus sur la figure 4) qui délimite le périmètre des opérations et en contrôle les entrées et les sorties. Des membres de FTDA et de l’UASA viennent établir les listes et répartir les individus en fonction de leurs profils (familles et femmes, mineurs, hommes) qui sont ensuite orientés vers différentes solutions d’hébergement où est examinée leur situation administrative (figure 5). Enfin, lorsque la mise à l’abri est terminée et s’il reste des personnes en attente de solution, les forces de l’ordre procèdent à la dispersion de l’occupation (voir le détail dans la loupe de la figure 4) pour vider l’espace de cette présence collective qui donnait une existence matérielle à la revendication.

Within the framework of the protest actions organised by the Réquisitions Collective, providing shelter began with the rollout of a police response (blue shapes in figure 4), which would set the operational perimeter and monitor who moved in and out of it. Members of FTDA and the UASA would draw up lists and classify individuals according to their profiles (families and women, minors, men), and direct them to different accommodation solutions where their administrative situation would be investigated (figure 5). Finally, when the shelter allocation process was finished and if there were still people waiting for a solution, the forces of law and order would break up the event (see details in the close-up in figure 4) and empty the area of the collective presence that gave material substance to the demands.

Les mises à l’abri engendrent une dépolitisation de l’action. Les associations du collectif sont sollicitées par les pouvoirs publics pour servir d’interface avec les personnes présentes. Elles sont mises à contribution pour dresser des listes, faire circuler l’information et aider à organiser les files. M. (U56) justifie cette implication par les compétences et les savoir-faire que son organisation et le collectif sont à même de déployer : « je pense qu’on est tous plus compétents d’un point de vue opérationnel […] sur chaque évac’ ils [les pouvoirs publics] mettent 20 000 ans à choper deux infos que t’as en deux minutes ». Pour répondre à la demande d’une partie des participants, le collectif organise progressivement ses actions dans le but d’obtenir une mise à l’abri, en occupant le lieu dans l’attente du dispositif :

Allocating temporary accommodation had the effect of depoliticising the protests. The authorities would ask the organisations in the Collective to act as an interface with the protesters. They would be tasked with drawing up lists, circulating information and helping to organise the queues. M. (U56) justifies this involvement by the skills and know-how that his organisation and the Collective were able to provide: “I think we’re all more competent from an operational point of view […] for each evacuation it takes them [the authorities] 20,000 years to get two pieces of information that we can get in two minutes.” In response to demand from some of the participants, the Collective gradually began to organise its protest events with the aim of getting people into shelter, occupying sites while waiting for the system to be put in place:

« La plupart de nos actions […] ça venait quand même d’une demande des personnes à la rue : “c’est eux qui organisent l’action à Paris et c’est ces actions-là qui sont actuellement le seul moyen d’avoir un hébergement, donc on veut y participer”. » (M., U56)

“Most of our operations […] were driven by demand from rough sleepers: ‘They are the ones organising action in Paris, and it is those operations that are currently the only way to get accommodation, so we want to take part’.” (M., U56)

Par conséquent, un glissement vers une logique d’assistance et d’aide humanitaire s’impose. Le paysage associatif et institutionnel local d’aide aux personnes à la rue – particulièrement aux exilés – voit le collectif Réquisitions comme un moyen d’accès à l’hébergement. Comme O. (PE) le résume : « on devient l’interface par laquelle les gens transitent, du coup on remplace des dispositifs ». Les participants aux actions viennent massivement pour la mise à l’abri. Ainsi, le 12 mai 2021, l’un des membres du collectif enjoint les participants à l’action à se maintenir sur la place de la République afin de créer un rapport de force. Cependant, dès l’arrivée d’un bus pour lancer l’opération de mise à l’abri, les participants se précipitent vers celui-ci, sans que tous puissent y accéder par ailleurs. Un homme dénonce avec colère avoir attendu toute la journée pour rien alors qu’il s’était vu promettre une prise en charge. Certaines des personnes présentes ne saisissent pas la dimension politique des actions et entretiennent un rapport de service avec le collectif. Plus globalement, les responsables de ce dernier pointent du doigt la limite posée par la mise à l’abri à la dimension revendicative des actions :

As a result, a transition took place towards processes of assistance and humanitarian aid. Local organisations and institutions that worked with rough sleepers–particularly exiles–saw the Réquisitions Collective as a means of accessing accommodation. As O. (PE) sums things up: “We are becoming an interface that people pass through, so we are now becoming a substitute for procedures.” The vast majority of people would take part in the operations in order to get shelter. So, for example, on 12 May 2021, one of the members of the Collective urged participants to remain on Place de la République in order to alter the balance of power. However, as soon as a bus arrived to begin the process of moving people to shelters, the participants rushed towards it, although not everyone was able to benefit. One man complained angrily about having waited all day for nothing when he had been promised support. Some of the people present did not understand the political dimension of the operations and saw the Collective as a service provider. More generally, the Collective’s leaders pointed out how the quest for accommodation reduced the protest dimension of the operations:

« T’es toujours sur la bascule entre le moment où tu es un acteur revendicatif, et tu vas te poser dans un endroit, et le moment où tu es un supplétif des pouvoirs publics, pour les aider à rassembler des gens et finalement, à faire la mise à l’abri que, de toute façon, ils sont obligés de faire. » (P., SMW)

“You’re always going back-and-forth between being an activist with demands, ready to occupy a public space, and becoming an adjuvant to the authorities, helping them to get people onside and, in the end, to provide the shelter that the authorities are obliged to provide anyway.” (P., SMW)

Ce brouillage vient aussi perturber la lecture que les participants aux actions peuvent avoir du collectif. Cette normalisation est contrecarrée dans une certaine mesure par la logique spatiale – revendiquer des espaces de pouvoir ou symboliques – qui maintient de façon ténue la politisation de la lutte.

This blurring of roles also disrupted the way the protest participants perceived the Collective. This normalisation was counteracted to some extent by the spatial component–occupying spaces that are representative of power or in some way symbolic–which tenuously maintained the political dimension of the struggle.

Ainsi, la mise à l’abri invisibilise la revendication d’accès au logement.

In this respect, the effect of gaining access to shelter was to mask the demand for access to accommodation.

« Pour eux [les pouvoirs publics] c’est plus collectif “Réquisitions”. C’est rien ! C’est plus que… “collectif camping” ! […] À mon avis, c’est de l’intelligence, comment ne pas donner de l’importance au mot “réquisition”. Parce que “hébergement”, “mise à l’abri”, ça n’a aucun rapport avec “réquisition”. » (B., CSP75)

“For them [the authorities] it’s no longer the Réquisitions Collective. It’s nothing! It’s nothing more than… a ‘camping group’! […] In my opinion, it’s a matter of intelligence, how can you not assign importance to the word ‘requisition’? Because ‘accommodation’ and ‘shelter’ have nothing to do with ‘requisition’.” (B., CSP75)

B. interprète les solutions d’hébergement comme une réponse permettant de faire taire la revendication de réquisition, « on met à l’abri 300, 400, 500 personnes, c’est mieux que parler du collectif Réquisitions dans les infos ». Or le logement n’est pas l’hébergement :

B. interprets the offer of temporary accommodation as a way to silence the demand for requisition: “we give 300, 400, 500 people a roof over their heads, it’s better than having talk about the Réquisitions Collective in the news”. However, accommodation is not housing.

« Il y a [une camarade] qui est transférée d’un endroit à un endroit. Bon, grâce au collectif, elle a jamais été à la rue. Mais si c’était son logement, on la change plus. […] Parce que quand on dit “logement”, on dit “stabilité”. » (B. CSP75)

“I have [a friend] who’s constantly being moved from one place to another. True, thanks to the Collective, she’s never been homeless. But if it was her home, it wouldn’t change any more. […] Because when we say ‘home’, we mean ‘stability’.” (B., CSP75).

Figure 5 : dispositif de mise à l’abri et hébergements successifs après l’évacuation de l’école du 16e arrondissement. Réalisation : Oriane Sebillotte, données ethnographiques, 2021

Figure 5: arrangements for providing shelter and successive accommodations after the evacuation of the school in the 16th arrondissement. Produced by: Oriane Sebillotte, ethnographic data, 2021

Cette instabilité transparaît dans le dispositif de mise à l’abri, avec un enchaînement de solutions d’hébergement et de transferts. Le dispositif présenté ici (figure 5), mis en place à la suite de la première occupation du collectif, est représentatif de celui qui s’applique après chaque action. Il diffère, quant à l’amplitude géographique, de l’évacuation du parc André Citroën qui a mené à l’orientation de plus de la moitié des participants vers des hébergements en région, ce qui a été perçu comme une forme de répression les éloignant de leurs territoires ressources (scolarisation, travail, relations). Peu à peu, la mise à l’abri est interprétée comme un outil du contrôle sociospatial qui a enfermé la revendication de la réquisition dans le registre de l’urgence.

This instability is reflected in the system for providing shelter, with a succession of accommodation solutions and transfers. The system presented here (figure 5), set up following the Collective’s first occupation, is representative of approach employed after each protest. It differs in geographical scope from the evacuation of Parc André Citroën, which led to more than half of the participants being steered towards accommodation in the region, which was perceived as a form of repression that distanced them from their resource territories (schooling, work, relationships). Little by little, shelter came to be interpreted as a tool of socio-spatial control, a way to divert the demand for requisition towards a solution for a social emergency.

Réprimer en limitant les violences policières

Cracking down while limiting police violence

La médiatisation des violences consécutives à l’évacuation de la place de la République, en novembre 2020, limite pendant quelque temps les violences policières à l’encontre du collectif. B. de la CSP75 remarque : « s’ils veulent utiliser la force, ils sont les maîtres. […] À mon avis, ils ne veulent même pas… C’est une manière de minimiser, c’est une façon de ne pas avoir plus de sympathisants avec nous ». Pour elle, les autorités évitent ainsi de créer les conditions d’une mobilisation en limitant la répression (Fillieule et Della Porta, 2006). Selon les membres du collectif les plus attachés à la revendication pour le logement, il s’agit, pour la préfecture, de dépolitiser la lutte au profit de solutions d’hébergement. Pour d’autres, plus enclins à approuver les mises à l’abri, l’attitude de la préfecture traduit une crainte et l’instauration d’un rapport de force : « ils nous ont pris un minimum au sérieux quand même, […] quand on déclarait un truc, ils disaient “bon, on leur ramène les bus sinon ils vont encore nous mettre des tentes à République” » (M. U56). P. (SMW) observe cependant que les pouvoirs publics sont prompts à se réadapter :

The media coverage of the violence that followed the evacuation of Place de la République in November 2020 for a while led to a reduction in police violence against the Collective. B., of the CSP75, notes: “If they want to use force, they can give the order. […] In my opinion, they don’t really want to… It’s a way of turning down the heat, a way to avoid getting more sympathisers on our side.” In her view, the authorities thus avoid creating the conditions for mobilisation by limiting repression (Fillieule and Della Porta, 2006). According to the members of the Collective who were most insistent in the demand for housing, the prefecture’s aim was to depoliticise the struggle by focusing on accommodation solutions. For others, more inclined to respond positively to the offer of accommodation of shelter, the prefecture’s attitude was a sign of fear and of a shift in the balance of power: “they took us at least a little seriously […] when we announced something, they would say ‘okay, we’ll bring back the buses or they’ll be putting up tents in Place de la République again’” (M., U56). P. (SMW) noted, however, that the authorities were quick to adapt:

« Entre la première opération et la dixième, la réaction n’est pas la même, et la dixième […] c’est une stratégie de force, de violence ! Envoyer 600 personnes en province, c’est un message qu’ils nous adressent. » (P., SMW)

“Between the first operation and the tenth, the reaction changed, and the tenth […] it’s a strategy of force, of violence! Sending 600 people to the provinces is a message they’re sending us.” (P., SMW)

Ainsi les pouvoirs publics, sans recourir à des évacuations violentes ni laisser l’ensemble des participants sans solutions, emploient malgré tout des méthodes répressives. D’abord dirigée contre les militants qui sont convoqués au commissariat à la suite de l’action à l’Hôtel-Dieu, elle se dirige ensuite contre les participants aux actions : « ils se sont dit : “on va attaquer les gens”, déjà en ne prenant pas tout le monde et pour signifier aussi que “vous n’êtes pas les chefs, c’est nous qui choisissons les places qu’on vous donne”, […] et, en plus, tu rapetisses la lutte » (O., PE).

So, without resorting to violent dispersal or leaving all the participants without accommodation options, the authorities nevertheless employed repressive methods. Initially targeting the activists who were summoned to the police station following the demonstration at Hôtel-Dieu, they were then directed against participants in the protests: “they decided: ‘we’re going to attack people,’ first by not taking everyone, and then by making it clear that ‘you’re not in charge, we’re the ones who decide what places we give you’, […] and, what’s more, it was a way to reduce the level of conflict” (O., PE).

Les relations avec les pouvoirs publics engendrent donc une démobilisation qui passe par la répression, des réponses discriminées en fonction des statuts administratifs, des relations de proximité avec les agents qui ne sont en mesure de proposer que des solutions routinières et opérationnelles qui effacent les revendications.

Relations with the authorities thus led to a loss of motivation through repression, discriminatory responses based on administrative status, and close relations with officials who were only able to propose routine and operational solutions without dealing with the fundamental demands.

Conclusion

Conclusion

Les actions du collectif Réquisitions dessinent un territoire de la lutte pour le logement conditionné par des arbitrages entre une revendication radicale et un objectif de visibilisation, les attentes des participants aux actions et l’anticipation de la répression. D’une part, les lieux occupés d’occupation permettent l’existence matérielle de la lutte par leur appropriation et leur spectacularisation qui interrogent et transgressent l’ordre des places en révélant ses inégalités au nom du principe d’égalité de tous avec tous (Rancière, 1995). D’autre part, les interactions avec les pouvoirs publics, et les priorités des participants – l’obtention d’un toit –, ont un impact démobilisateur au regard des revendications initiales, mais permettent la continuité de la lutte et des solutions immédiates qui reproduisent les hiérarchies sociospatiales. L’analyse de cette mobilisation se situe à une échelle collective, dans un temps limité et à travers le rapport de force spatial qui s’établit entre les individus non ou mal logés et les pouvoirs publics. Les trajectoires de (dés)engagement des personnes concernées (Fillieule, 2005) et le rôle parfois ambivalent des responsables-organisateurs du collectif – qui peuvent, malgré eux, reproduire les hiérarchies sociales qu’ils dénoncent par le déroulement des actions et des prises de décisions – sont des pistes complémentaires pour comprendre la (dé)mobilisation sous l’angle de la construction des subjectivations politiques (Tassin, 2014). D’autres luttes récentes gagneraient à être étudiées dans une perspective comparative afin d’interroger ce phénomène de reproduction sociale dans les mobilisations de migrants et d’approfondir et de nuancer la compréhension des engagements individuels.

The activities of the Réquisitions Collective marked out a territory of struggle for housing influenced by the trade-offs between the pursuit of radical outcomes and the goal of awareness-raising, the demands of the participants in the protest actions and the expectation of repression. On the one hand, the occupation of high-profile sites kept the struggle alive materially through appropriation and public impact, and thereby challenged and transgressed the hierarchy of places by revealing its inequalities vis-à-vis the principle of universal equality (Rancière, 1995). On the other hand, interactions with the authorities, and the priorities of the participants–to get a roof over their heads–had a demobilising impact with respect to the initial demands, while allowing the struggle to continue and the enactment of immediate solutions that reproduced the socio-spatial hierarchies. This mobilisation needs to be analysed on a collective scale, within a limited timeframe and through the spatial balance of power established between homeless or poorly housed individuals and the authorities. The trajectories of (dis)engagement of the people concerned (Fillieule, 2005) and the sometimes ambivalent role of the Collective’s leaders-organisers–who may, in spite of themselves, have reproduced the social hierarchies they condemned in the manner that they implemented protests and took decisions–offer further potential ways to understand (de)mobilisation in terms of the construction of political subjectivations (Tassin, 2014). It would be worth studying other recent struggles from a comparative perspective in order to examine this phenomenon of social reproduction in migrant mobilisations and to further extend and qualify our understanding of individual engagements.

Pour citer cet article

To quote this article

Piva Annaelle, Sebillotte, 2025, « Territoire d’une lutte pour le droit au logement à Paris, géographie d’une mobilisation et de son contrôle : le cas du collectif Réquisitions » [“Territory of a struggle for the right to a home in Paris, geography of a mobilisation and its suppression: the case of the Réquisitions Collective”], Justice spatiale | Spatial Justice, 19 (http://www.jssj.org/article/territoire-dune-lutte-pour-le-droit-au-logement-a-paris-geographie-dune-mobilisation-et-de-son-controle-le-cas-du-collectif-requisitions/).

Piva Annaelle, Sebillotte, 2025, « Territoire d’une lutte pour le droit au logement à Paris, géographie d’une mobilisation et de son contrôle : le cas du collectif Réquisitions » [“Territory of a struggle for the right to a home in Paris, geography of a mobilisation and its suppression: the case of the Réquisitions Collective”], Justice spatiale | Spatial Justice, 19 (http://www.jssj.org/article/territoire-dune-lutte-pour-le-droit-au-logement-a-paris-geographie-dune-mobilisation-et-de-son-controle-le-cas-du-collectif-requisitions/).

[1] Selon la Cour des comptes dans son rapport public annuel de 2021, les centres d’hébergement dénombrent 260 000 places fin 2019. En 2022, la Fondation abbé Pierre décompte un peu plus de 1 million de personnes sans logement (hébergées ou à la rue) dans son rapport annuel sur le mal-logement.

[1] According to the 2021 annual public report of the Cour des Comptes, there were 260,000 places in accommodation centres at the end of 2019. In 2022, the Abbé Pierre Foundation estimated in its annual report on housing shortages that there were a little over a million people without homes (living in shelters or on the streets).

[5] Carte interactive en ligne, « Data Portraits Paris/Grand Paris – arrondissements, communes, territoires », Atelier parisien d’urbanisme (APUR).

[5] Online interactive map, “Data Portraits Paris/Grand Paris – arrondissements, communes, territoires”, Atelier parisien d’urbanisme (APUR).

[6] Agnès Stienne, 2012, « Cartographie des lieux de pouvoir à Paris », parue dans Manière de voir, 122 (https://www.visionscarto.net/lieux-de-pouvoir-a-paris, consulté le 20/03/2024).

[6] Agnès Stienne, 2012, “Cartographie des lieux de pouvoir à Paris”, published in Manière de voir, 122 (https://www.visionscarto.net/lieux-de-pouvoir-a-paris, accessed 20/03/2024).

[7] « “Rendre visibles les invisibles” à Paris, 400 sans-abri s’installent sur la chic et très touristique place des Vosges », RTBF, 29 juillet 2021.

[7] “’Rendre visible les invisibles’” in Paris, 400 homeless people take up residence on the chic and very touristy Place des Vosges”, RTBF, 29 July 2021.