Introduction

Introduction

En 1990, les peuples indigènes[1] d’Amazonie bolivienne ont marché jusqu’à la capitale, La Paz, pour dénoncer la dépossession foncière dont ils étaient les victimes, et la menace que celle-ci faisait peser sur leur survie. Face aux éleveurs et aux forestiers, ils se sont emparés de l’espace pour demander justice. « La marche pour le territoire et la dignité » est la geste héroïque de la Bolivie contemporaine. Elle allie dans une même révolte les demandes de terres et de reconnaissance, et fait entrer de plain-pied les peuples indigènes dans l’espace politique ouvert par les réformes néolibérales entreprises en Bolivie dans les années 1990. Depuis, en l’espace d’un quart de siècle, les peuples indigènes ont obtenu des terres et la reconnaissance identitaire a nettement progressé. Les réformes constitutionnelles ont intégré peu à peu la composante indigène dans la définition de la nation, faisant de la Bolivie un État multiculturel (1994) puis plurinational (2009). La participation politique indigène s’est développée, symbolisée par l’élection à la présidence d’Evo Morales en 2005, premier président indigène des Amériques, et même au-delà.

In 1990, the indigenous peoples of the Bolivian Amazon marched to the capital, La Paz, to protest about the dispossession of their lands, and about the threat that this posed to their survival. Faced with the cattlemen and timber companies, they seized space in order to demand justice. “The march for territory and dignity” was the heroic event in the history of contemporary Bolivia. It combined in a single uprising the demands for land and recognition, and brought indigenous peoples fully into the political space opened up by the neoliberal reforms undertaken in Bolivia in the 1990s. Since then, in the space of a quarter of a century, indigenous peoples have obtained land, and the recognition of their identity has markedly progressed. Constitutional reforms gradually incorporated the indigenous component into the definition of the nation, making the state of Bolivia first multicultural (1994) and then plurinational (2009). Indigenous political participation developed, symbolised by the election to the presidency in 2005 of Evo Morales, first indigenous president in the Americas, and even beyond.

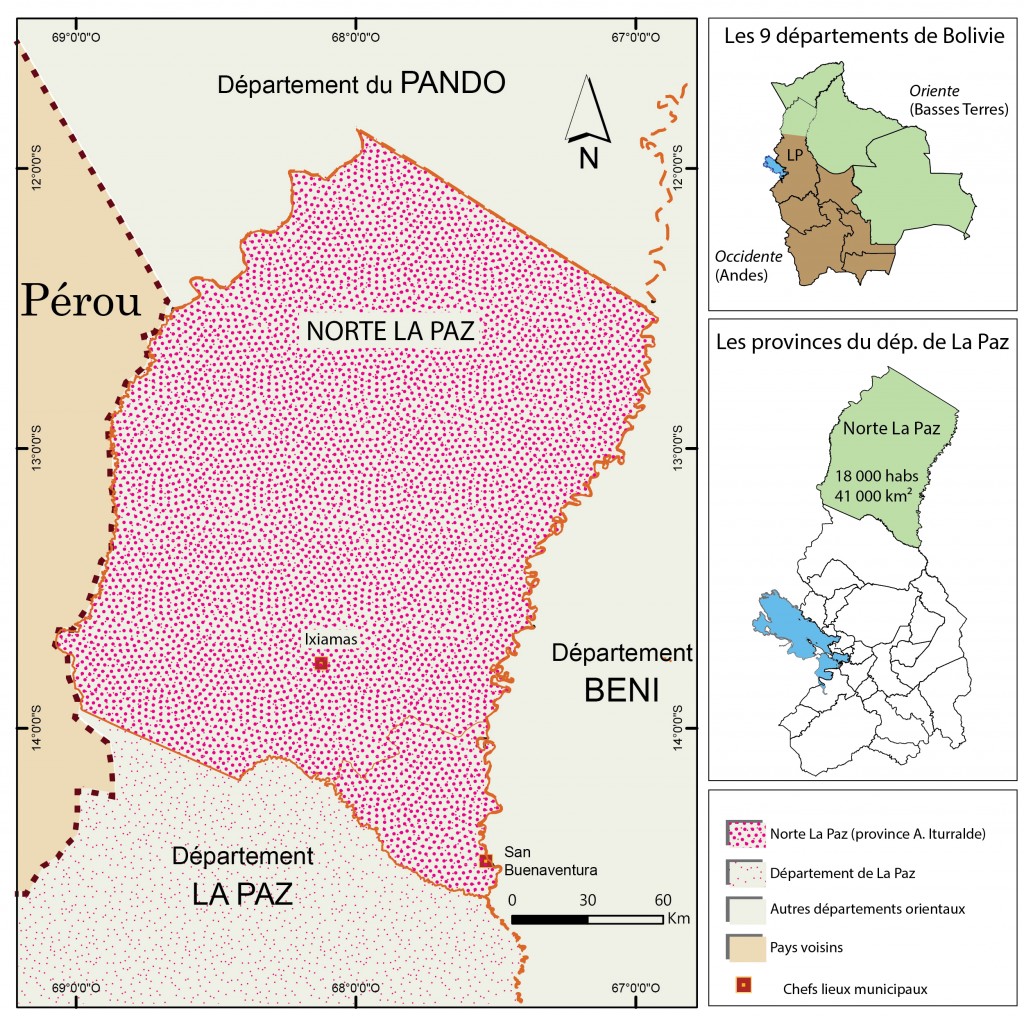

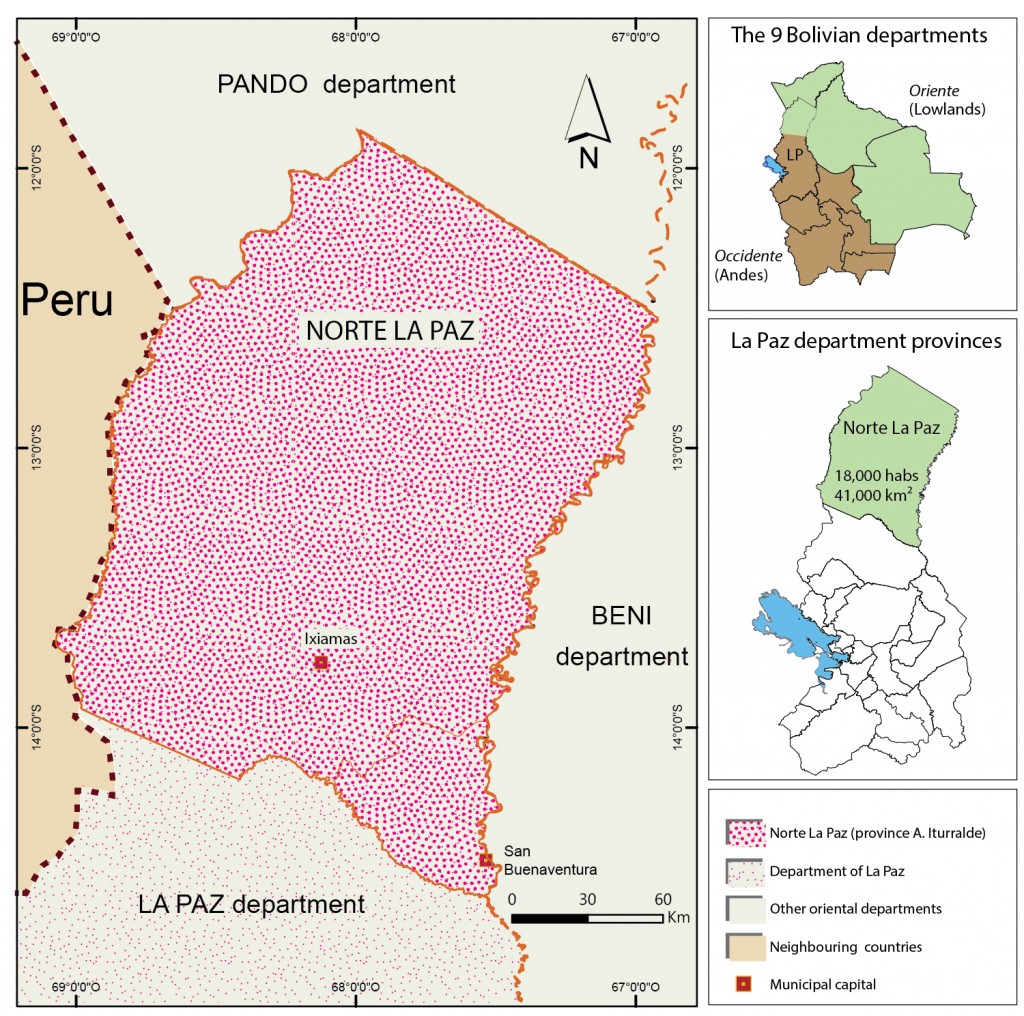

En Bolivie, il semble donc que justice a été faite aux peuples indigènes. La cession des terres a ouvert la voie à une réparation complète qui inclut la distribution, la reconnaissance et la participation, conformément à la définition tridimensionnelle de la justice proposée par Iris Young (1990) puis Nancy Fraser (2000). Cependant, l’analyse des processus concrètement mis en œuvre pour obtenir réparation doit être conduite avec minutie, comme nous y invitent les coordinatrices de ce numéro thématique, car la mise en cohérence de ces trois principes d’équité, de reconnaissance et de participation n’est pas évidente. Dans le Norte La Paz (Carte 1), la partie amazonienne du département de La Paz, la question de la justice reste au cœur des relations sociales, preuve que le processus de réparation n’est pas achevé.

In Bolivia, therefore, it would seem that justice has been done to the indigenous peoples. The transfer of land opens the way for full reparation, including distribution, recognition and participation, in accordance with the three-dimensional definition of justice proposed by Iris Young (1990) and Nancy Fraser (2000). However, a meticulous analysis of the actual processes implemented to obtain reparation is required, as the coordinators of this thematic issue have invited us to do, since it is not easy to bind these three principles of equity, recognition and participation into a coherent whole. In Norte La Paz (see Map 1), the Amazonian part of the Department of La Paz, the issue of justice remains at the heart of social relations, evidence that the process of reparation is not complete.

Carte 1 : Localisation du Norte de La Paz

Map 1: Location map of Norte La Paz

Dans cet espace rural de faible densité (18 000 habitants pour 42 000 km²) (INE, 2012), les populations, en dehors des trois bourgs principaux, vivent dans des communautés paysannes, sorte de villages où dominent la mono-activité agricole et le poids du groupe soudé par la propriété collective de la terre. Les communautés des peuples indigènes[2], celles des paysans colonisateurs venus des Andes, à partir de la fin des années 1970, et les migrants récemment arrivés dans le Norte La Paz s’opposent autour des questions foncières. La terre est non seulement source de conflits mais aussi au cœur des procédures de justice : objet de l’injustice initiale, via la dépossession foncière, elle a été envisagée par ces différents acteurs comme le moyen de la réparation. A leurs yeux, elle doit permettre de rétablir l’équité, en tenant compte des besoins différenciés de chacun des groupes. La terre, repensée comme territoire, doit aussi être le support de la reconnaissance identitaire et de la participation politique. A partir du cas du Norte La Paz, et du peuple indigène tacana, qui représente un tiers de la population de la province (6180 personnes auto-déclarées Tacanas en 2012) (INE, 2012), je souhaite montrer que le processus par lequel l’espace permet de rétablir la justice est plus complexe et plus ambivalent que dans l’énoncé des deux propositions ci-dessus. L’attribution de terres répare-t-elle l’injustice en renvoyant les peuples indigènes à un état antérieur à la dépossession foncière ou engage-t-elle ces derniers dans une nouvelle relation au territoire et à l’environnement ? L’octroi d’un territoire peut-il garantir une reconnaissance culturelle pleine et entière, c’est-à-dire qui intègre la permanente construction de l’identité, ou conduit-il à l’élaboration d’une identité figée et standardisée ? Il s’agit, en somme, de se demander si la proposition de penser la justice dans sa triple dimension n’ouvre pas la voie à de nombreuses contradictions lorsqu’il s’agit de mettre en œuvre un processus de réparation.

In this low-density rural area (18,000 people per 42,000 km²) (INE, 2012), the populations – outside the three main towns – live in peasant communities, villages of a kind dominated by rural mono-activity and by groups bound together through collective land tenure. The communities of indigenous peoples,[1] of the settler peasants from the Andes who settled there in the late 1970s, and of migrants recently arrived in Norte La Paz, are competing for land access. Land is not only a source of conflict but also at the heart of legal procedures: initially a source of injustice through land dispossession, it is perceived by these different actors as the means of reparation and the way whereby equity can be re-established, taking into account the different needs of each of the groups. Land, reconceived as territory, should also be the medium for the recognition of identity and for political participation. Through the case of Norte La Paz, and the indigenous Tacana people who account for one third of the population of the province (6180 self-declared as Tacana in 2012) (INE, 2012), I wish to show that the process whereby space is used to re-establish justice is more complex and more ambivalent than the statement of these two propositions might suggest. Does the allocation of land make reparation for injustice by restoring the indigenous peoples to their pre-dispossession state or does it engage them in a new relation to the territory and the environment? Can the granting of a territory guarantee full and integral cultural recognition, i.e. one that includes the permanent construction of identity, or does it lead to the imposition of a fixed and standardised identity? In sum, the aim is to explore whether the proposal to consider justice in its threefold dimension does not open the way to numerous contradictions in the context of a process of reparation.

Les résultats d’une enquête conduite entre 2012 et 2015 dans le Norte La Paz apportent quelques éléments de réponse. Le corpus est constitué d’un ensemble d’entretiens et de questionnaires qui révèlent la diversité des stratégies territoriales des acteurs. La littérature relative à la justice environnementale et la façon dont elle a été mise en œuvre dans les Suds sert de cadre théorique pour mettre en perspective ce corpus (Schlosberg, 2004 ; Schroeder et al., 2008 ; Walker, 2012 ; Martin et al., 2014). J’entends démontrer l’intérêt d’une approche par le territoire des questions de justice spatiale et environnementale, dans un contexte marqué par la présence de peuples indigènes. Je révèle aussi comment la construction identitaire des peuples indigènes se déploie au travers de stratégies scalaires : changement d’échelles des luttes indigènes, du local au global (Cox, 1998 ; Kurtz, 2003) et fabrication d’échelles, au sens d’espace d’action politique (Tsing, 2000). Je reprends la question, maintes fois posée, du passage des principes universels de justice à leur application dans un contexte local, toujours particulier (Wenz, 1988 ; Harvey, 1996 ; Schlosberg, 2004). Enfin, je mets en discussion les approches anthropologiques qui enferment les peuples indigènes dans des catégories stables, isolées et a-historiques (Taussig, 1987 ; Whiteman, 2009), en postulant que les constructions identitaires indigènes s’élaborent toujours dans le dialogue avec l’extérieur, aux frontières de l’ethnicité (Barth, 1999).

The findings from a survey conducted between 2012 and 2015 in Norte La Paz go some way to providing answers. The materials consist of a set of interviews and questionnaires that reveal the diversity of the actors’ territorial strategies. The literature relating to environmental justice and the way that it has been implemented in the Global South is used as a theoretical framework through which these materials are approached (Schlosberg, 2004; Schroeder et al., 2008; Walker, 2012; Martin et al., 2014). I intend to show the value of tackling questions of spatial and environmental justice – in a context marked by the presence of indigenous peoples – from a territorial perspective. I also show how the identities of indigenous peoples are constructed through politics of scale: changes from the local to the global in the scales of indigenous struggle (Cox, 1998; Kurtz, 2003), and the production of scales viewed as the spaces of political action (Tsing, 2000). I explore the question that has been asked so many times about the transition from universal principles of justice to their application in a local and always specific context (Wenz, 1988; Harvey, 1996; Schlosberg, 2004). Finally, I open up a debate on anthropological approaches that enclose indigenous peoples within fixed, isolated and ahistorical categories (Taussig, 1987; Whiteman, 2009), by postulating that the constructions of indigenous identity always take place in a dialogue with the exterior, at the boundaries of ethnicity (Barth, 1999).

La première partie de ce texte montre l’omniprésence des questions de justice dans le Norte La Paz et la façon dont l’enquêteur-trice y est confronté-e. La deuxième partie analyse comment l’octroi de terres (puis de territoires) a ouvert la voie à une justice complète assurant l’équité, la reconnaissance culturelle et la participation politique. Enfin, la troisième partie expose les limites de cette justice par le territoire et la reconnaissance culturelle parfois imparfaite à laquelle elle donne lieu.

The first part of this text shows the omnipresence of issues of justice in Norte La Paz and how they confront investigators. The second part analyses how the granting of land (then territories) opened the way to full justice, guaranteeing equity, cultural recognition and political participation. Finally, the third part exposes the limitations of this justice through territory and the sometimes imperfect cultural recognition to which it gives rise.

Justice et injustice : narrations autour des reconfigurations territoriales en Amazonie bolivienne

Justice and injustice: narratives around territorial reconfigurations in the Bolivian Amazon

Etudier les processus d’intégration en Amazonie bolivienne pour découvrir la justice au cœur des débats

Studying integration processes in the Bolivian Amazon in order to explore the justice at the heart of the debates

En 2012, le projet CAPAZ[3] a réuni, autour de la question des effets socio-politiques de l’intégration en Amazonie bolivienne, des historiens et géographes de l’université de La Paz (UMSA), dont l’auteure de cet article. Il posait la question de la résilience des acteurs locaux (paysans communautaires et peuples indigènes) face au processus d’insertion de la province dans des espaces plus vastes, lequel processus est conduit par des institutions étatiques ou mondialisées (organisations non gouvernementales, agences de coopération internationale etc.). L’aire d’étude était circonscrite au Norte La Paz, laboratoire des politiques néolibérales en faveur des droits indigènes dans les années 1990, avant de devenir un lieu emblématique du retour de l’État central à partir de 2010 (Perrier Bruslé, Gosalvez, 2014).

In 2012, the CAPAZ project brought together historians and geographers from La Paz University (UMSA), including the author of this article, around the subject of the sociopolitical effects of integration in the Bolivian Amazon.[2] It raised the question of the resilience of local actors (peasant communities and indigenous peoples) to the integration of the province into larger spaces, a process conducted by state or global institutions (NGOs, international cooperation agencies, etc.). The area of study was limited to Norte La Paz, first a laboratory of neoliberal policies in favour of indigenous rights in the 1990s, then an iconic location for the return of the central state after 2010 (Perrier Bruslé, Gosalvez, 2014).

La justice spatiale n’était pas l’objet initial de cette recherche. Elle s’avéra pourtant être un élément déterminant des stratégies des acteurs. Car dans le Norte La Paz, peuples indigènes et colons, forestiers et petits agriculteurs, éleveurs et commerçants se font face et opposent leurs arguments pour obtenir justice par l’octroi de terres. Les uns évoquent le besoin d’espace agricole pour leurs enfants, les autres la nécessité de préserver un capital foncier ou encore la réparation d’une injustice historique. Les distributions de terres effectuées par l’État sont toujours évaluées à l’aune d’une justice placée au centre des relations sociales. Constamment discutée, la justice n’a, dans le Norte La Paz, rien d’un concept abstrait. Si elle est un objectif partagé par tous, chacun en a sa propre conception. Les entretiens que j’ai conduits avec mes collègues géographes étaient traversés par cette question. Les interviewés nous prenaient constamment à témoin de ce qu’ils considéraient comme des injustices dans la répartition de l’espace[4].

Spatial justice was not the initial subject of this research. However, it proved to be a crucial aspect of the actors’ strategies. This is because, in Norte La Paz, indigenous peoples and settlers, loggers and small farmers, cattlemen and traders, confront each other and advance opposing arguments to obtain justice through the granting of land. Some speak of the need for farmland for their children, others of the necessity of protecting land or repairing an historical injustice. Distributions of land by the state are always assessed in terms of a justice that is at the heart of social relations. A constant topic of discussion, justice in Norte La Paz has nothing of the abstract concept about it. It might be a shared goal, but each perceives it in their own way. The interviews I conducted alongside my geographer colleagues were saturated with this question. The interview subjects constantly asked us to bear witness to perceived injustices in the allocation of space.[3]

L’Amazonie bolivienne, théâtre des luttes indigènes pour davantage de justice dans les années 1990

The Bolivian Amazon, arena of indigenous struggles for justice in the 1990s

La question de la justice renvoie au récit, qui se cristallise dans les années 1990, d’un passé marqué par la dépossession des terres. Le Norte La Paz, comme les autres régions orientales, a traditionnellement été considéré comme une frontière agricole qui, bien qu’habitée par des peuples indigènes, devait servir le développement national (Fifer, 1967 ; Groff Greever, 1987 ; Perrier Bruslé, 2007). Toutefois, l’injonction à peupler et exploiter l’Oriente est restée longtemps sans conséquences. Tout change à partir des années 1960. Dans l’esprit de la réforme agraire de 1953, qui souhaite résoudre les problèmes d’inégalités foncières dans les Andes et impulser le développement agricole, les Basses Terres deviennent le lieu d’un double mouvement d’occupation. Le plan national de colonisation agraire (1963-1965) distribue des terres à des dizaines de milliers de paysans andins venus coloniser les piémonts andins, dans le Chaparé et dans les Yungas. Devenus adultes, leurs enfants s’installent dans le Norte La Paz dans les années 1970, seconde étape de cette trajectoire migratoire familiale, tandis que d’autres colons viennent directement de l’Altiplano et de Tarija, dans le sud de la Bolivie. Dans le même temps, le secteur agro-capitaliste se déploie dans la région (Gill, 1987 ; Sanabria, 1993 ; Bottazzi, Rist, 2012 ; Colque, Tinta, Sanjines, 2016). Sur les 26 millions d’hectares qui reçoivent des titres de propriété dans l’Oriente entre 1953 et 1993, 88% sont attribués à de moyens ou grands propriétaires (Pacheco, Urioste, 2000). En outre, dans le Norte La Paz, à côté des propriétés dédiées à l’élevage, l’exploitation forestière progresse (Hunnisett, 1997 ; Pacheco, 2005).

The question of justice relates to the narrative, which crystallised in the 1990s, of past land dispossession. Norte La Paz, like the other Eastern regions of Bolivia, was traditionally considered an agricultural boundary which, though inhabited by indigenous peoples, was to serve national development (Fifer, 1967; Groff Greever, 1987; Perrier Bruslé, 2007). However, the injunction to populate and exploit the Oriente long remained without consequence. Everything began to change in the 1960s. In the spirit of the agrarian reform of 1953, which sought to resolve the problems of land inequalities in the Andes and to drive agricultural development, the Lowlands became the focus of a twin occupation movement, driven on the one hand by the small farmers, and on the other by the agri-capitalist sector. The national agrarian colonisation plan (1963-65) distributed land to tens of thousands of Andean peasants who came to settle in the foothills of the Andes, in Chapare and in Yungas. In the 1970s, the grown children of these settlers moved to Norte La Paz, the second stage in this story of family migration, while other settlers came directly from Altiplano and Tarija, in the south of Bolivia. At the same time, the agri-capitalist sector moved into the region (Gill, 1987; Sanabria, 1993; Bottazzi Rist, 2012; Colque, Tinta, Sanjines, 2016). Out of the 26 million hectares in the East on which land titles were granted between 1953 and 1993, 88% were allocated to medium or large landowners (Pacheco and Urioste, 2000). In addition, in Norte La Paz, forestry developed alongside land dedicated to cattle breeding (Hunnisett, 1997; Pacheco, 2005).

Petits colons, grands propriétaires et exploitants forestiers sont dès lors perçus comme une menace par les peuples indigènes, d’autant plus que leurs titres de propriété sont fragiles ou inexistants. Ils ont, en outre, peu de moyens pour les défendre. Ils ne sont pas représentés par des syndicats agraires puissants comme dans les Andes et sont stigmatisés dans les textes de loi (Bottazzi, 2009). En réponse à cette situation, les peuples de l’Oriente fondent en 1982 la Confédération des peuples et communautés indigènes de l’Oriente bolivien (CIDOB - Central de Pueblos y Comunidades Indígenas del Oriente Boliviano). En 1990, « la marche pour le territoire et la dignité » réunit des centaines de personnes. Largement médiatisée, cette mobilisation change la face de la Bolivie pour toujours (Postero, 2007). Elle chasse soudain de l’invisibilité les peuples indigènes des Basses Terres (Assies, 2006). La même année, le président de la République, Paz Zamora, entend leur demande de justice et y répond par la création des quatre premiers territoires indigènes[5]. La relation entre injustice, réparation par la terre et reconnaissance identitaire est posée.

Small settlers, large landowners and loggers were thus perceived as a threat by the indigenous peoples, especially as their land titles were fragile or non-existent and they had few resources to defend them. They lacked representation by powerful farming unions like those in the Andes, and were subject to discriminatory legislation (Bottazzi, 2009). In response to this situation, in 1982 the peoples of the East founded the Confederation of Indigenous Peoples and Communities of the Bolivian Oriente (CIDOB – Central de Pueblos y Comunidades Indígenas del Oriente Boliviano). In 1990, hundreds joined “the march for territory and dignity”, a mobilisation that generated extensive media coverage and changed the face of Bolivia for ever (Postero, 2007): suddenly, the indigenous peoples of the Lowlands were no longer invisible (Assies, 2006). In the same year, President of the Republic Paz Zamora responded to their demand for justice with the creation of the first four indigenous territories.[4] The connection between injustice, reparation through land, and identity recognition, was established.

L’injustice spatiale s’élabore dans un espace pluriscalaire, la réparation aussi

Spatial injustice develops in a space of multiple scales, as does reparation

Retenons de ce moment l’importance d’étudier les mécanismes qui ont généré l’injustice jusqu’à conduire à son énonciation. En effet, évaluer les injustices, les qualifier et en repérer les victimes ne suffit pas. L’injustice spatiale est le résultat d’un processus qui s’élabore dans des relations pluriscalaires où l’espace local se trouve abruptement mis en contact avec des espaces de pouvoir extérieurs (Schroeder et al., 2008). Dans le Norte La Paz, l’État, au nom du développement, ainsi que les entreprises privées à la recherche de profits, ont été ces agents extérieurs qui ont généré l’iniquité.

Let us retain from this moment the importance of studying the mechanisms that generated injustice, and led ultimately to its recognition. Assessing the injustices, describing them, and identifying their victims is not enough. Spatial injustice is the outcome of a process that develops through transcalar relations, where local space comes abruptly into contact with the spaces of external powers (Schroeder et al., 2008). In Norte La Paz, the state, on grounds of development, together with private companies in search of profit, were the external agents that generated injustice.

Ce processus pluriscalaire qui produit l’injustice présente bien des similitudes avec celui qui œuvre à sa réparation. En effet, là encore, des acteurs extérieurs à l’espace local où se joue la dépossession sont moteurs : Églises, grandes agences internationales ou nationales, ONG, organisations syndicales et politiques etc. (Lavaud, Lestage, 2006). Le cas de l’anthropologue allemand Jürgen Riester, qui fonde à la fin des années 1970 l’ONG Soutien au paysan indigène de l’Oriente bolivien (APCOB - Apoyo Para el Campesino – Indígena del Oriente Boliviano) afin d’organiser des rencontres entre plusieurs groupes indigènes de l’Oriente (Chiquitano, Ayoreo puis Guaranis, Guarayo et Mataco), est exemplaire en la matière. En 1982, ce sont ces groupes qu’il a mis en contact qui fondent ensemble la CIDOB (Postero, 2007). Les ONG ont aussi joué un rôle actif dans l’organisation matérielle de la marche de 1990 (Boulding, 2014). Leur soutien est légitimé par un discours international favorable à la cause indigène depuis les années 1970 (Postero, 2007 ; Brysk, 2000). Certes, les peuples indigènes de l’Oriente ne sont pas de simples spectateurs : ils participent activement à l’élaboration de ces réseaux. Il n’en reste pas moins que c’est bien dans un espace pluriscalaire que se déploie leur lutte. En somme, le processus par lequel justice est faite – ou demandée - est fort similaire dans son inscription spatiale au processus qui a généré, et peut générer encore, de l’injustice.

The transcalar process that produced this injustice had many similarities with the process involved in its reparation. Here again, the drivers were actors from outside the local space in which the dispossession had taken place: churches, big international or national agencies, NGOs, union and political organisations, etc. (Lavaud, Lestage, 2006). A typical example is the case of the German anthropologist Jürgen Riester, who in the late 1970s founded the NGO Support for Eastern Bolivia’s Indigenous-Peasant (APCOB – Apoyo Para el Campesino – Indígena del Oriente Boliviano) to develop contacts between a number of indigenous groups from the Oriente (Chiquitano, Ayoreo, then Guaranis, Guarayo and Mataco). It was these groups which together founded CIDOB in 1982 (Postero, 2007). NGOs also played an active role in the material organization of the 1990 march (Boulding, 2014), legitimised in their support by international advocacy of the indigenous cause that dated back to the 1970s (Postero, 2007; Brysk, 2000). Of course, the indigenous peoples of the Oriente were not mere spectators, and were themselves actively involved in developing these networks. Nonetheless, their struggle took place within a space of multiple scales, so it is legitimate to say that the process whereby justice was done – or demanded – was very similar in its spatial configuration to the process that generated, or can still generate, injustice.

Faire justice par le territoire : distribution, reconnaissance et participation

Doing justice through territory: distribution, recognition, and participation

A la recherche d’une justice complète par le territoire

Seeking full justice through territory

Après la marche indigène de 1990, le territoire devient une « icône » autour de laquelle s’organisent les relations entre les peuples indigènes et l’État (Postero, 2007, p. 49). Le passage d’une problématique de la terre à une problématique du territoire, et donc de reconnaissance culturelle, permet d’aller au-delà d’une justice libérale fondée sur la seule recherche de l’équité via un modèle distributif (Rawls, 1971 ; Barry, 1995). L’octroi de terres ne se limite plus à une allocation de moyens destinés à compenser une position sociale défavorisée, dans l’esprit des mesures de discrimination positive. Les peuples indigènes n’acceptent pas non plus un simple partage des bénéfices tirés de l’exploitation des ressources car leur pauvreté pourrait transformer cette redistribution en un moyen de coercition économique (Schroeder, 2008) : en échange du partage des bénéfices, on pourrait en effet leur demander de renoncer à certains de leurs droits territoriaux.

After the 1990 march, territory became an “icon” around which relations between the indigenous peoples and the state were organized (Postero, 2007, p. 49). The transition from an issue of land to an issue of territory, and therefore of cultural recognition, took the process beyond one of liberal justice founded on the simple quest for equity via a distributive model (Rawls, 1971; Barry, 1995). The granting of land was no longer restricted to the allocation of resources in compensation for a disadvantaged social position, in the spirit of positive discrimination. Nor did the indigenous peoples accept a simple sharing of the profits earned from the exploitation of resources, because their poverty could turn this redistribution into a means of economic coercion (Schroeder, 2008): this is because, in exchange for a share of the profits, they could be asked to give up some of their territorial rights.

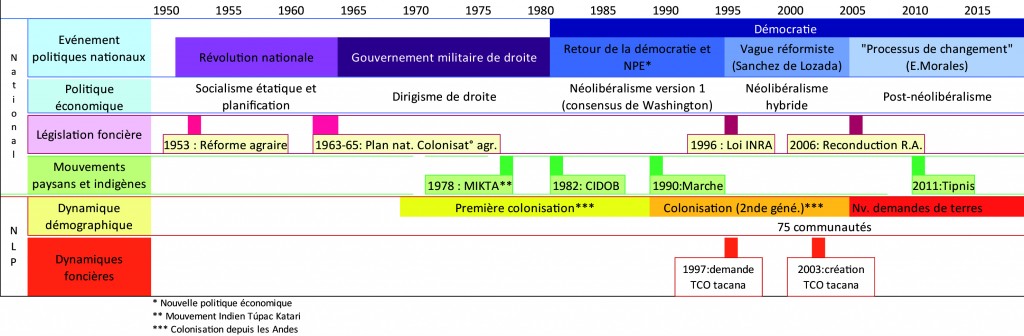

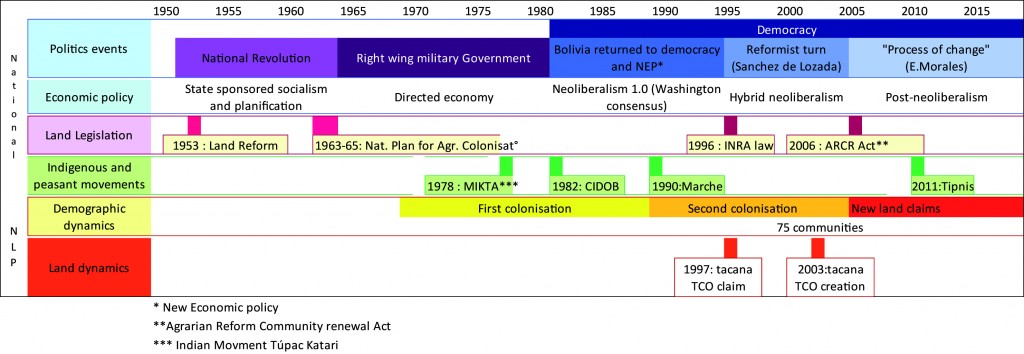

Ainsi, à partir des années 1990, les terres se retrouvent en Bolivie au centre des procédures de réparation, ce qui permet à la justice post-libérale (ou post-rawlsienne) de se déployer dans ses trois dimensions, telles que définies par Fraser (2000), Schlosberg (2004) et Young (1990). Les terres sont tout à la fois l'objet de la réparation (car elles permettent la distribution des ressources), le support de la réparation (car elles ouvrent la voie à la reconnaissance de territoires culturels) et le levier pour obtenir davantage de justice (car via la gestion des terres, les peuples indigènes participent pour la première fois à la gouvernance locale). La figure 1 permet de resituer ce tournant dans l’histoire politique nationale des mouvements agraires.

From the 1990s, therefore, land in Bolivia was once again at the heart of reparation procedures, source of a post-liberal (or post-Rawlsian) justice operating in its three dimensions, as defined by Fraser (2000), Schlosberg (2004) and Young (1990). Land was simultaneously the method of reparation (since it allowed the distribution of resources), the medium of reparation (because it opened the way to the recognition of cultural territories), and a lever for obtaining further justice (since through land management, the indigenous peoples were involved for the first time in local governance). Figure 1 illustrates this turning point in the national political history of agrarian movements.

Figure 1 : Chronogramme des mouvements agraires nationaux et locaux

Figure 1: Chronogram of national and local agrarian movements

La loi INRA de 1996 : réparer en distribuant des terres et des ressources

The INRA Law of 1996: reparation through the distribution of land and resources

La justice spatiale, via l’octroi de terres, se déploie dans le cadre légal de la loi INRA, du nom de l’Institut national en charge d’appliquer la réforme agraire (Instituto Nacional de Reforma Agraria). Promulguée en 1996, elle relance la réforme agraire un demi-siècle après la première loi de 1953, dont les effets en termes de justice, en particulier pour les peuples indigènes, avaient été mitigés. Edictée sous la pression du mouvement indigène oriental (Lema, 2001 ; Postero, 2007), elle participe de l’émergence d’un néolibéralisme hybride (voir figure 1). En Bolivie, au tournant des années 1990, le paradigme néolibéral initial, défini par le consensus de Washington, évolue (Larner, 2003). Un projet ambitieux de réorganisation politico-sociale via la promotion d’une gouvernance locale (Stokke, Mohan, 2001) et la reconnaissance des cultures indigènes (Hale, 2005) est lancé. Le multiculturalisme est dans l’air du temps. L’accession au poste de vice-président de Victor Hugo Cárdenas (1992), leader aymara, et la réforme constitutionnelle (1994) qui fait de la Bolivie un « État multiethnique et une nation pluriculturelle » (art. 1), témoignent de l’importance accordée à la question indigène au moment de promouvoir une gouvernance locale (Perrier Bruslé, 2015).

Spatial justice, in the form of land allocation, was delivered through the legal framework of the INRA Law, named after the national institute responsible for applying agrarian reform (Instituto Nacional de Reforma Agraria). Passed in 1996, it reinstated agrarian reform half a century after the first law of 1953, which in terms of justice, particularly for the indigenous peoples, had been mixed in its effects. Promulgated under pressure from the Eastern indigenous movement (Lema, 2001; Postero, 2007), the INRA Law was also consistent with a form of hybrid neoliberalism (see Figure 1). In Bolivia in the early 1990s, the original neoliberal paradigm defined by the Washington consensus was evolving (Larner, 2003). An ambitious plan was launched for political and social reorganisation via the promotion of local governance (Stokke, Mohan, 2001) and the recognition of indigenous cultures (Hale, 2005). Multiculturalism was in the air. The accession of Aymara leader Victor Hugo Cárdenas (1992) to the post of vice-president, and the constitutional reform (1994) that made Bolivia a “multi-ethnic state and pluricultural nation” (art. 1), reflect the importance attributed to the indigenous question at a time when the promotion of local governance was a political goal (Perrier Bruslé, 2015).

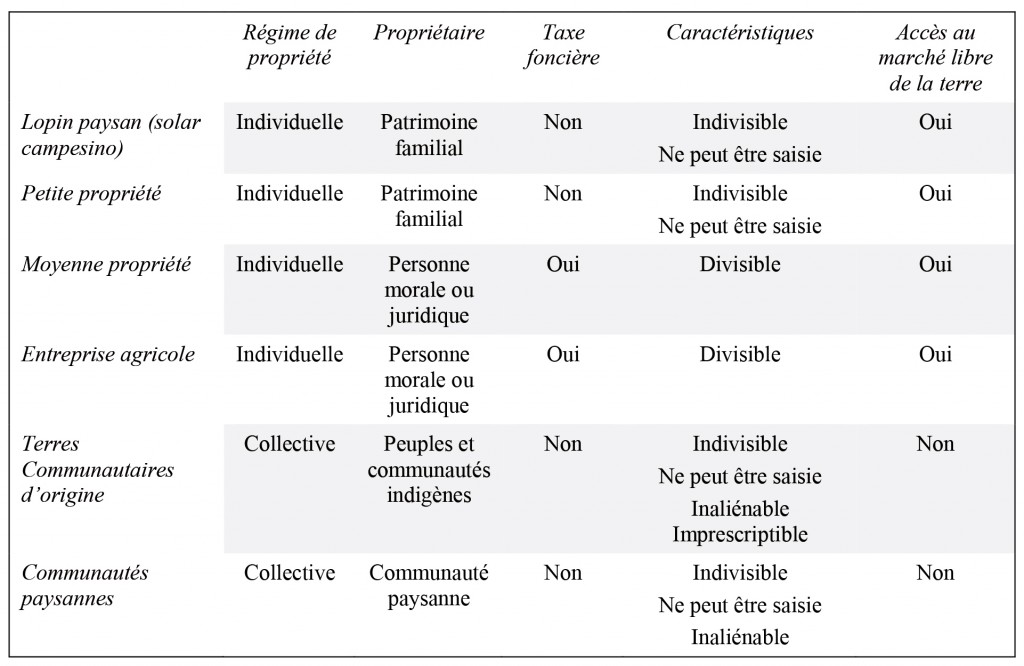

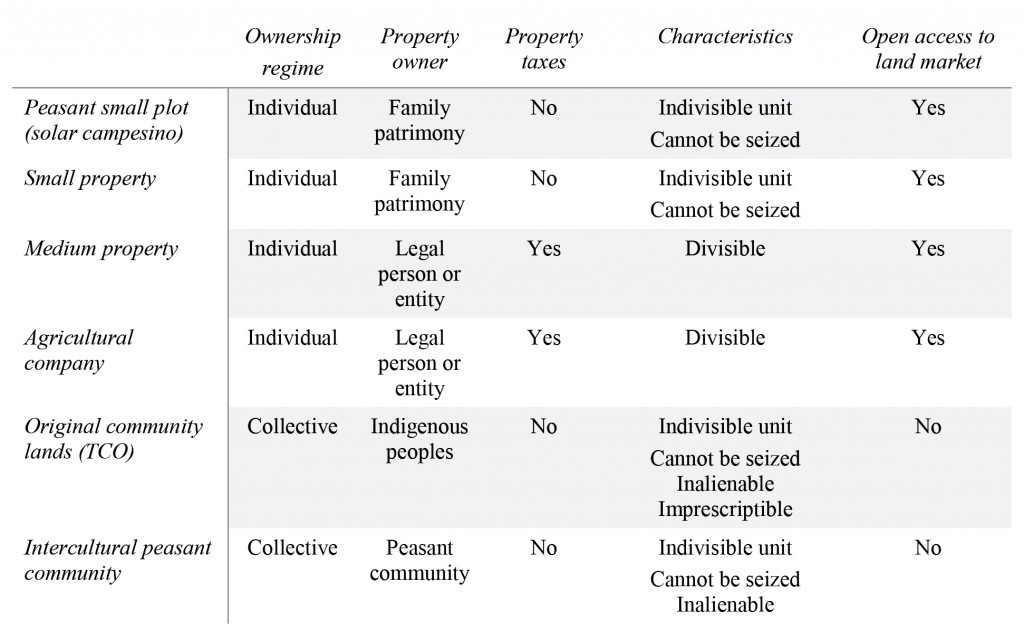

Inscrite dans ce contexte néolibéral hybridé, la loi INRA est donc tout à la fois libérale, au sens où elle entend favoriser la liberté économique, et indigéniste. Son objectif est de créer un marché foncier en régularisant les cadastres (Hecht, 2005 ; Farthing, Kohl, 2014), et de moderniser le secteur agricole en empêchant la spéculation foncière via l’interdiction de détenir des terres sans les travailler. La loi présente en outre un versant indigéniste et social. La régularisation du foncier permet d’identifier les terres fiscales, c’est-à-dire appartenant à l’État et pouvant, à ce titre, être octroyées à des peuples indigènes et à des paysans sans terre. Le régime du marché libre de la terre n’est donc pas total car deux catégories de tenure foncière lui échappent (figure 2) : les terres des communautés paysannes et celles des peuples indigènes, dites Terres communautaires d’origine (TCO - Tierras Comunitarias de Origen), relèvent de titres collectifs et ne peuvent faire l’objet d’une transaction commerciale (Pacheco, Urioste, 2000).

Embedded in this hybrid neoliberal context, the INRA Law was therefore simultaneously liberal, in the sense that it sought to foster economic freedom, and indigenist. Its objective was to create a market inland by bringing the land registry up-to-date (Hecht, 2005; Farthing, Kohl, 2014), and to modernise the farming sector by preventing land speculation and the holding of unworked land. In addition, the act had an indigenist and social dimension. The regularisation of land titles made it possible to identify fiscal lands, i.e. land that belonged to the state and could therefore be granted to indigenous peoples and landless peasants. The free market system for land was therefore not total, since it excluded two categories of land tenure (Figure 3): the lands of the peasant communities and of the indigenous peoples, so-called Original Community Lands (TCO – Tierras Comunitarias de Origen), were held under collective title and could not be bought and sold (Pacheco, Urioste, 2000).

Figure 2 : Régimes fonciers établis par la loi INRA (art. 41)

Figure 2: Land tenure regimes established by the INRA Law (Art.41)

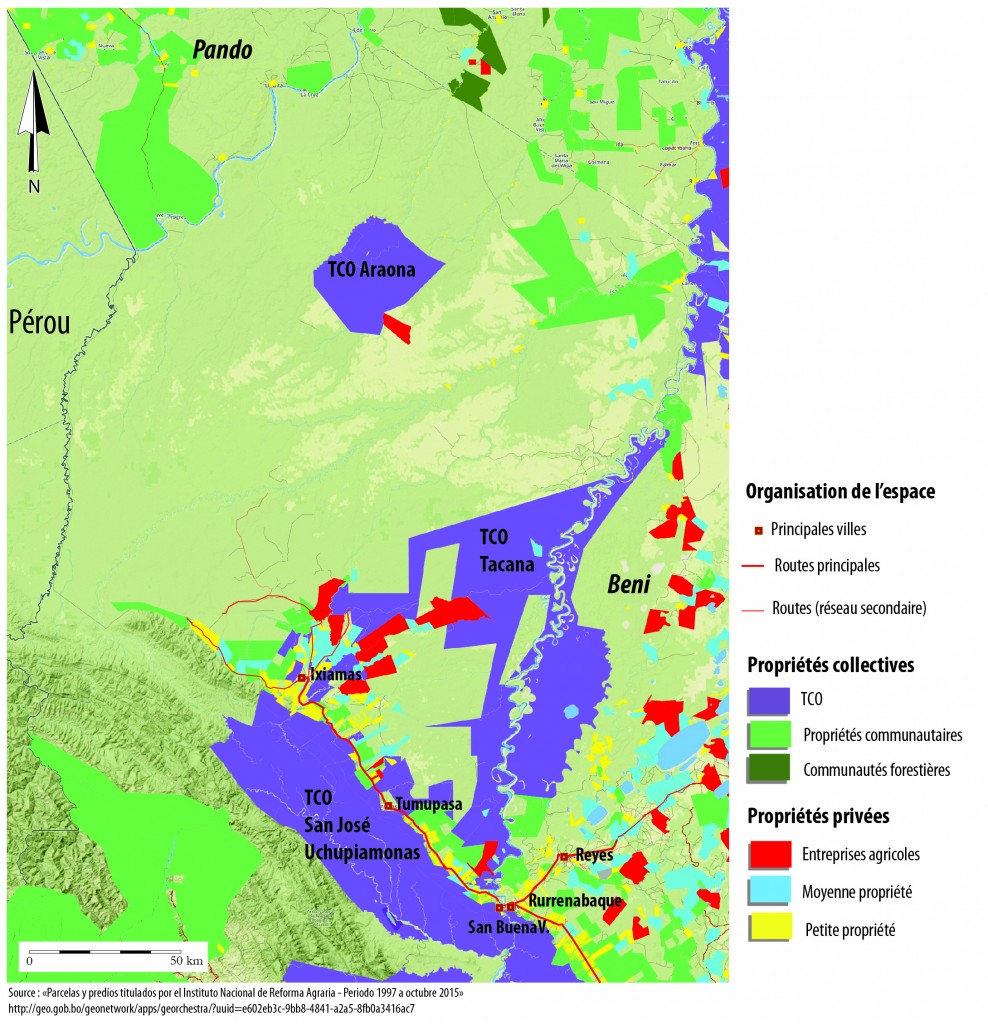

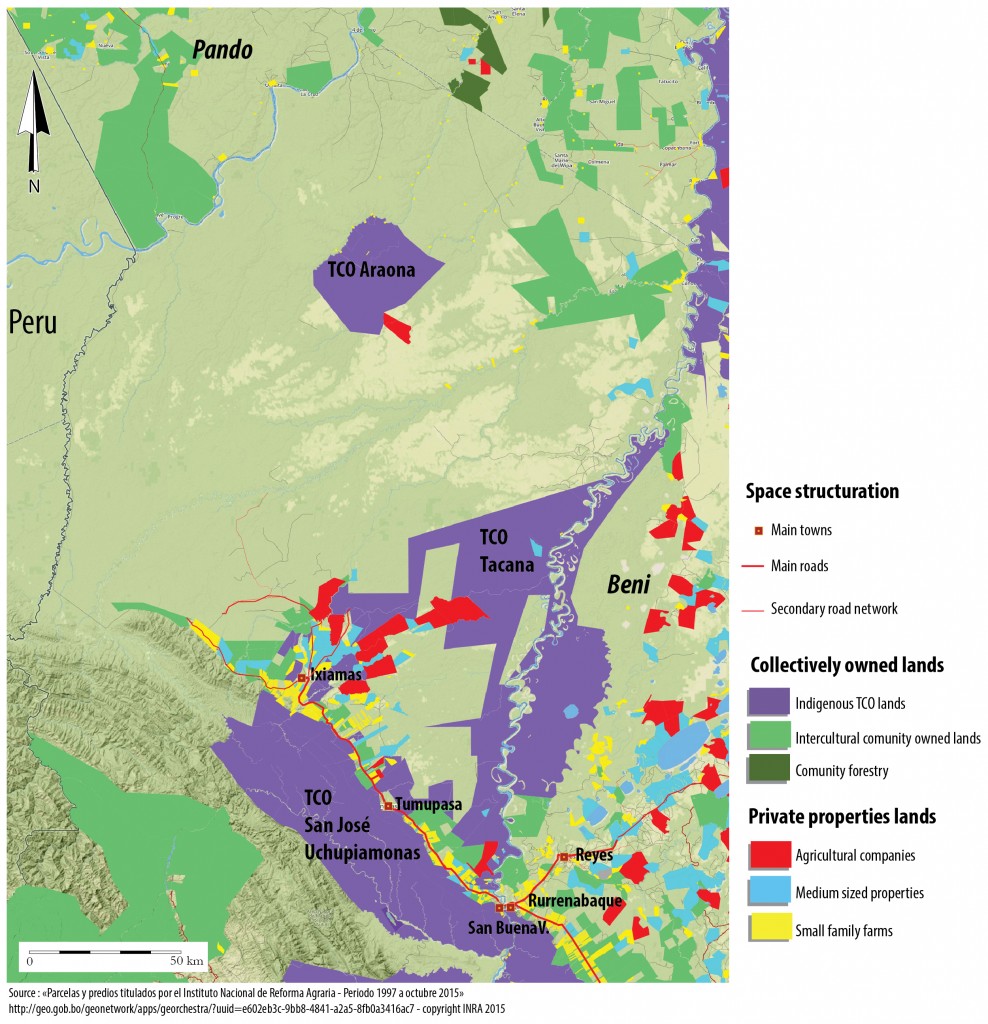

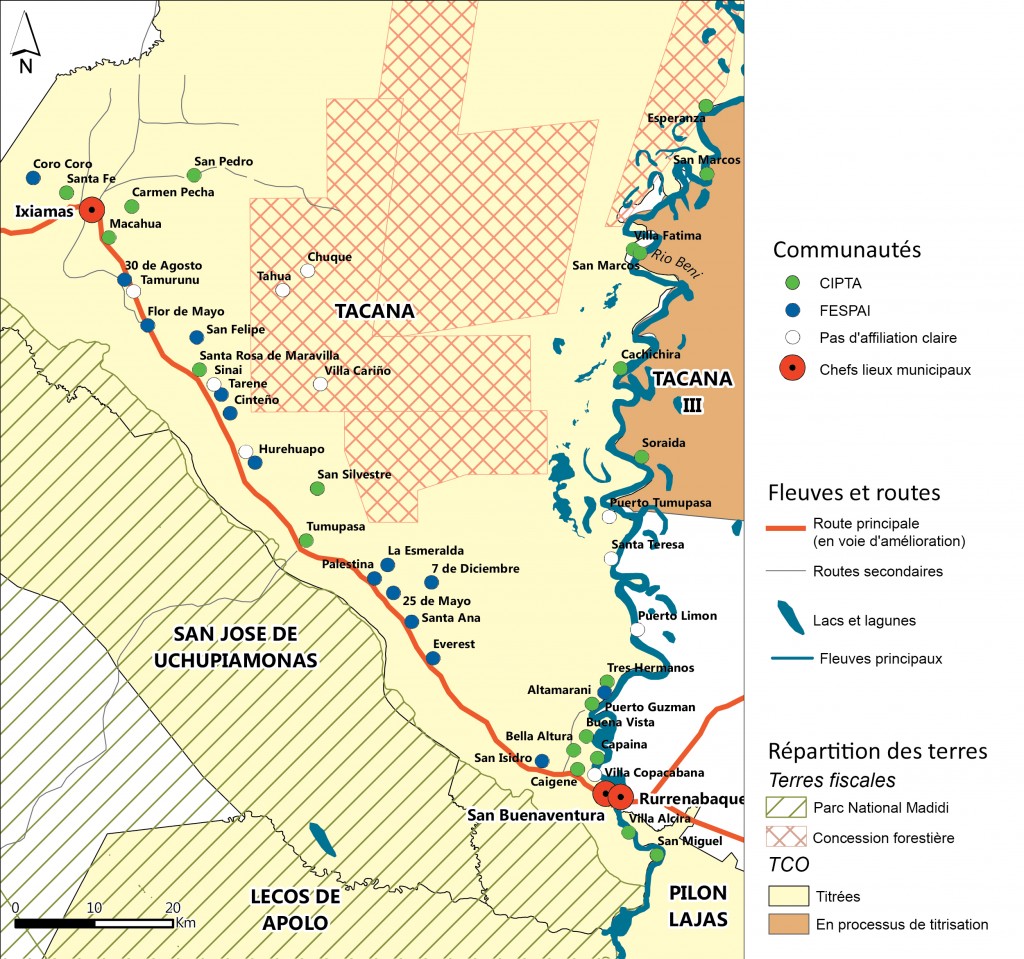

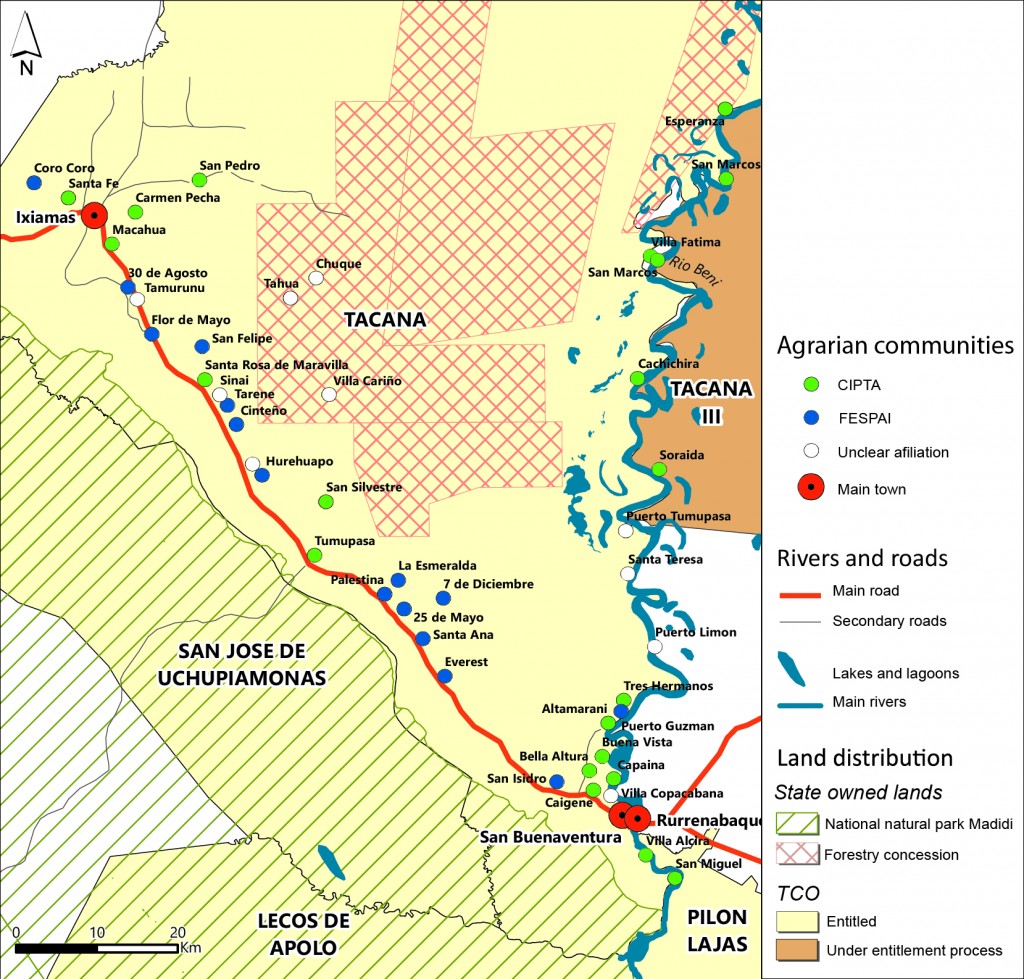

Dans le Norte La Paz, trois TCO sont créées : Tacanas, San José de Uchupiamonas et Araona (Carte 2). Dans le même temps, les paysans colonisateurs obtiennent des titres fonciers collectifs pour une vingtaine de communautés.

In Norte La Paz, three TCOs were created: Tacanas, San José de Uchupiamonas, and Araona (Map 2). At the same time, the settler farmers obtained collective land titles for some twenty communities.

Carte 2 : TCO attribuées entre 1997 et 2015 dans le Norte La Paz

Map 2: Map of TCOs allocated between 1997 and 2015 in Norte La Paz

Si l’attribution de terres aux peuples indigènes et aux paysans communautaires ne leur permet pas d’accéder au marché foncier, elle les intègre toutefois aux réseaux marchands. Les peuples indigènes, notamment, peuvent exploiter le bois de leur TCO (art. 32, Loi forestière n°1700, 1996), alors même que le Norte La Paz connaît un boom forestier depuis 1985. C’est ainsi que l’attribution de terres, même non cessibles, participe d’une justice distributive via la marchandisation du bois. Nous reviendrons plus avant sur les effets ambivalents de cette redistribution foncière.

Although the allocation of land to the indigenous peoples and peasant communities did not give them access to the land market, it nevertheless brought them into market networks. The indigenous peoples, in particular, could exploit the timber on their TCOs (Art. 32, Forestry Act No. 1700, 1996), at a time when Norte La Paz had been experiencing a logging boom since 1985. In this way the allocation of land, even unsaleable land, contributed to distributive justice through the commodification of timber. We will subsequently look at these ambivalent effects of the land redistribution.

Attribution de terres et reconnaissance identitaire

Allocation of lands and recognition of identity

L’établissement d’une nouvelle justice spatiale initiée en 1996 par les politiques publiques boliviennes va plus loin que ce modèle distributif : elle ouvre aussi la voie à la reconnaissance culturelle des peuples indigènes. Les importantes surfaces foncières qui leur sont attribuées (figure 3) sont en effet justifiées, dans la loi INRA, par « la spécificité de leur organisation économique, sociale et culturelle » afin qu’ils puissent « assurer leur survie et leur développement » (art. 41, Loi INRA, 1996). Cette relation entre reconnaissance culturelle et attribution de terres n’est pas remise en question lorsqu’Evo Morales, élu en 2005, entreprend de transformer la Bolivie. La voie « post-néolibérale » dans laquelle il engage son pays est pleines d’ambiguïtés tant les éléments de rupture avec le néolibéralisme le disputent à la continuité (Freitas, Marston, et Bakker 2015)[6]. Sur la question des peuples indigènes de l’Oriente, le virage est en revanche clair et le divorce annoncé, alors que la période néolibérale avait été plutôt favorable à la cause indigène. Le retour de l’État relance les projets de colonisation agraire qui menacent les peuples indigènes. La loi de reconduction de la réforme agraire émise en 2006 témoigne de la faveur donnée aux paysans communautaires qui demandent des terres à coloniser. Dans le même temps, la nouvelle Constitution politique de l’Etat (CPE) de 2009 brouille et affaiblit la catégorie « indigène » en y associant les termes « paysan » et « originaire ». Le but est de parvenir à l’union des mouvements populaires, paysans et indigènes, qui soutiennent le gouvernement[7]. Cependant, si la cause des colons progresse, en raison du soutien indéfectible du syndicalisme paysan au gouvernement, des éléments de continuité, favorables aux territoires indigènes, subsistent malgré tout. Les TCO deviennent des Territoires indigènes originaires et paysans (TIOC - Territorios Indígena Originario Campesinos) (art. 393 à 404, CPE 2009). Par conséquent, si la catégorie « indigène » semble avoir été attaquée, le passage de la notion de terre à celle de territoire porte en revanche la promesse de création de territoires autonomes indigènes.

The establishment of a new spatial justice, initiated in 1996 by Bolivia’s public policies, went much further than this distributive model: it also opened the way for the cultural recognition of the indigenous peoples. The large areas of land allocated to them (Figure 5) were in fact justified, in the INRA Law, by “the specificity of their economic, social, and cultural organization” so that they could “continue to survive and develop” (Art. 41, INRA Law, 1996). This connection between cultural recognition and huge land allocation was not challenged when Evo Morales, elected in 2005, undertook to transform Bolivia. The “post-neoliberal” path down which he took his country remains full of ambiguities, with a tussle between factors representing a breakaway from neoliberalism and those representing continuity (Freitas, Marston, Bakker, 2015).[5] On the question of the indigenous peoples of the Oriente, on the other hand, the U-turn was clear and the divorce declared, whereas the neoliberal period had been broadly favourable to the indigenous cause. The return of the state also marked a resumption of the projects for agrarian settlement, again threatening the indigenous peoples. The Agrarian Reform Community renewal Act of 2006 reflected the preference given to peasant communities seeking land for settlement. At the same time, the new State Political Constitution (CPE) of 2009 blurred and weakened the “indigenous” category by combining it with the terms “peasant” and “native”. The aim was to bring about a union of working-class, peasant and indigenous movements, all of which supported the government.[6] However, although the cause of the settlers progressed, as a result of the peasant unions’ unwavering support for the government, elements of continuity favourable to the indigenous territories nevertheless persisted. The TCOs became original indigenous and peasant territories (TIOC – Territorios Indígena Originario Campesinos) (Art. 393 to 404, CPE 2009). In consequence, while the “indigenous” category appeared to be under attack, the transition from the notion of land to the notion of territory conversely brought the promise of the creation of autonomous indigenous territories.

Il reste qu’en liant catégorie ethnique et attribution de terres, le processus de réparation initié en 1996 a des conséquences qui vont plus loin que la reconnaissance d’une identité déjà existante : il stimule une (re)construction identitaire. Le cas bien documenté des Tacanas du Beni en fournit une illustration. Sous l’effet de la nouvelle loi INRA, ces Tacanas se constituent en groupe ethnique, au nom duquel ils formulent leur demande de terres. L’année 1996, date de la promulgation de la loi INRA, marque un tournant. L’existence ténue et insaisissable des Tacanas du Beni change brutalement (Herrera Saramiento, 2006 ; Herrera Saramiento, 2002) : ceux qui s’appelaient tous simplement les « fils de Tacanas », c’est-à-dire qui liaient leur identité indigène à une histoire individuelle et familiale, commencent à élaborer des marqueurs d’identité collective. Dans le Norte La Paz, la même relation dynamique entre demande de terres et définition identitaire se met en place. L’ancien-directeur du collège de San José de Uchupiamonas, âgé d’une soixantaine d’années aujourd’hui, s’est présenté en entretien comme un témoin de ces évolutions. Né à Tumupasa, au cœur de la province, il a fait carrière comme professeur dans les différentes écoles du Norte La Paz. Il nous a expliqué que « les gens se disaient Tacanas depuis bien longtemps déjà, ils étaient Tacanas, simplement parce que leurs grands-parents étaient Tacanas. Mais à cette époque, l’identité s’était perdue. C’était un moment de décadence. Même dans les écoles, lorsque nous étions enfants, on nous interdisait de parler tacana » (J.A.T, San Buenaventura, 29/04/2013). Comme dans le Beni, la filiation personnelle sert donc de premier argument ethnique : on est et naît Tacana parce qu’on est fils de Tacanas. Les Tacanas du Norte La Paz n’ont donc que peu de référents identitaires sur lesquels s’appuyer au moment de formuler leurs demandes foncières au nom de leur peuple. La directrice de l’Institut pour la langue et la culture tacanas, fondé en 2013, brosse le même tableau d’une culture tacana menacée dans les années 1990. Née à Tumupasa, de parents et grands-parents tacanas, comme elle aime à le souligner, cette dirigeante historique des Tacanas ne parle pas la langue de son peuple. Rétrospectivement, elle évoque une vague conscience commune qui aurait préexisté à la demande de terres : « Il y a toujours eu les connaissances, nous avons toujours su que nous étions Tacanas » (N.C.1, Tumupasa, 30/04/2013). Le caractère vague des « connaissances » mentionnées par la directrice de l’Institut tacana prouve que la reconnaissance légale, actée par la création de la TCO, ne signifie pas l’aboutissement d’une construction identitaire collective, mais son point de départ, comme s’il restait à donner du sens au contenant territorial, une fois celui-ci créé. Ce processus a d’ailleurs fait l’objet de négociations. Aidés par des organisations étrangères (Églises, ONG), les Tacanas formulent non pas une mais deux demandes : une pour la TCO Tacana, l’autre pour San José de Uchupiamonas. Cette partition s’explique par la volonté d’indépendance de San José. La pratique de deux langues indigènes, le tacana et le quechua, parlé à San José[8], justifie cette décision, ce qui témoigne de l’importance de la langue, même peu pratiquée, comme fondement identitaire à partir duquel il est possible de (re)construire une identité collective et donner une dimension territoriale aux terres concédées.

Nevertheless, by linking ethnic category to land allocation, the reparation process began in 1996 had consequences that went beyond the recognition of an already existing identity: it stimulated the (re)construction of identity, exemplified by the well documented case of the Tacanas of the Beni department. Under the provisions of the new INRA Law, these Tacanas declared themselves an ethnic group, and formulated a request for land on that basis. Then, with the promulgation of the Law in 1996, the tenuous and elusive existence of the Tacanas of Beni changed suddenly (Herrera Saramiento, 2006; Herrera Saramiento, 2002): people who simply called themselves “sons of Tacanas”, in other words linked their indigenous identity to an individual and family history, began to develop markers of collective identity. In Norte La Paz, the same dynamic relationship between land applications and identity construction arose. When interviewed, the former director of San José de Uchupiamonas secondary school, now aged around sixty, described himself as a witness to these changes. Born in Tumupasa, in the heart of the province, he pursued a career as a teacher in the different schools of Norte La Paz. He explained that “people had been calling themselves Tacanas for a long time, they were Tacanas simply because their grandparents were Tacanas. But at that time, our identity had been lost. It was a time of decadence. Even in the schools, when we were children, we were forbidden to speak Tacanas” (J.A.T, San Buenaventura, 29/04/2013). As in Beni, parentage was the primary ethnic argument: one was Tacana because one was a son of Tacanas. The Tacanas of Norte La Paz therefore had few criteria of identity on which to base their land requests. The Director of the Institute for the Tacana Language and Culture, founded in 2013, paints the same picture of a Tacana under threat in the 1990s. Born in Tumupasa, of Tacana parents and grandparents, as she likes to insist, this former leader of the Tacanas does not speak her people’s tongue. In retrospect, she recalls a vague communal awareness that perhaps existed before the application for land: “There was always knowledge, we always knew that we were Tacanas” (N.C.1, Tumupasa, 30/04/2013). The vague nature of the “knowledge” mentioned by the Director of the Tacana Institute shows that legal recognition, enacted by the creation of the TCO, signified not the culmination of the collective construction of identity, but its starting point, as if – once created – the territorial container needed to have meaning poured into it. Moreover, this process was subject to negotiation. With the help of foreign organisations (churches, NGOs), the Tacanas formulated not one but two requests: one for the Tacana TCO, the other for San José de Uchupiamonas, a partition justified by San José’s Tacana people’s wish for independence. The existence of two indigenous languages, Tacana and Quechua, the latter spoken in San José,[7] explains this decision, which shows the importance of language, even a little-used language, as a foundation of self-awareness from which a collective identity could be reconstructed and a territorial dimension imprinted on the land.

Une fois la demande arbitrée, ce territoire en formation devient un socle fédérateur bien plus puissant que la langue oubliée et les quelques évocations d’un mode de vie traditionnel. La directrice de l’Institut Tacana le reconnaît : « En tant qu’organisation, le plus important a été de lutter pour le territoire. Nous avons consolidé la TCO. Ce n’est certes pas suffisant et nous continuons à lutter pour consolider ce qui manque » (N.C.1, Tumupasa, 30/04/2013). La plupart de nos interlocuteurs tacanas, y compris le président actuel du conseil tacana (N.C.2, Buenavista, 29/09/2012), sont incapables de dire depuis quand la TCO existe, comme si ce territoire fondateur devait, pour gagner en puissance, échapper à la contingence d’une histoire récente qui l’a vu naitre.

Once the request was granted, this emerging territory became a much more powerful unifying force than the forgotten language and the few references to a traditional way of life, a fact acknowledged by the Director of the Tacana Institute: “As an organization, the most important thing was to fight for the territory. We consolidated the TCO. Of course, this is not sufficient and we continue to struggle to consolidate what is lacking” (N.C.1, Tumupasa, 30/04/2013). Most of the Tacanas we interviewed, including the current president of the Tacana Council (N.C.2, Buenavista, 29/09/2012), are incapable of saying how long the TCO has existed, as if – in order to gain in power – this foundational territory had to be spared the contingency of a birth witnessed in recent history.

Le territoire moteur de nouvelles luttes : la participation

Territory as the driver of new struggles: participation

Le territoire est cependant plus qu’un support identitaire. En permettant la participation des peuples indigènes à la vie politique, il engage la Bolivie des années 1990 dans un processus de justice totale, où « équité, reconnaissance et participation sont totalement intriquées » (Schlosberg, 2004, p. 527, ma traduction). La participation fait justice parce qu’elle est la condition de décisions justes, mais aussi parce qu’elle assure l’expression de la liberté de chacun (Sen, 2009 ; Martin et al., 2014).

However, the territory is more than a medium of identity. By enabling the indigenous peoples to participate in political life, it committed 1990s Bolivia to a process of total justice, in which “equity, recognition, and participation are intricately woven together” (Schlosberg, 2004, p. 527). Participation confers justice because it is the condition of just decisions, but also because it allows each person to express their freedom (Sen, 2009; Martin et al., 2014).

Dans le Norte La Paz, la participation des peuples indigènes est impulsée par la création des TCO. Tout d’abord, les demandes foncières motivent la constitution d’organes de représentation qui deviennent les canaux de la participation indigène à la vie politique nationale. A leur tête, la CIDOB organise des marches indigènes (1990, 1996, 2000), propose des projets de loi (tel que le projet de loi indigène de 1992, finalement abandonné) et place la question indigène au cœur des débats politiques (Postero, 2007). Comme les autres directoires de TCO, le conseil tacana est lié organiquement à la CIDOB. La participation politique des peuples indigènes est aussi confortée par l’administration des TCO, comme en témoigne la multiplication des plans de gestion du territoire et de ses ressources (CIPTA, 2003 ; 2008). Pourtant, initialement, la loi INRA de 1996 n’avait pas vocation à faciliter l’accès à la gouvernance des peuples indigènes. Le terme de « terres communautaires » (dans l’acronyme TCO) n’a pas été choisi au hasard : il s’agissait de distribuer du foncier, et non de créer des territoires en risquant ainsi de conduire à une fragmentation du pays (Assies, 2006)[9]. Cependant, par le biais du contrôle des ressources, les directoires des TCO sont devenus de facto des acteurs de la gouvernance locale (Perrier Bruslé, 2015). Ils se sont révélés être un canal efficace pour discuter directement avec l’État. A l’heure où les conflits pour l’accès à de nouvelles terres se multiplient, le directoire tacana fait donc entendre sa voix dans les lieux de pouvoir où s’organise la justice spatiale.

In Norte La Paz, the participation of the indigenous peoples was driven by the creation of the TCO. Initially, land applications prompted the establishment of representative bodies which became channels for indigenous participation in national political life. At their head, CIDOB organized marches by indigenous peoples (1990, 1996, 2000), proposed legislation (like the ultimately abandoned indigenous act of 1992) and placed indigenous issues at the heart of political debate (Postero, 2007). Like the other TCO management structures, the Tacana Council is organically linked with CIDOB. The political participation of the indigenous peoples was also reinforced by their own administration of the TCO, as evidenced by the proliferation of management plans for the territory and its resources (CIPTA, 2003; 2008). Initially, nonetheless, the intention of the 1996 INRA Law was not to make things easier for the indigenous peoples. The choice of the term “community lands” (in the acronym TCO) was not an accident: the aim was to distribute land, not to create territories and thereby run the risk of fragmenting the country (Assies, 2006).[8] However, through control of resources, the boards of the TCOs became de facto actors in local governance (Perrier Bruslé, 2015). They also proved to be an effective channel for direct access to central government. At a time when conflicts over access to new land were proliferating, the Tacana Council could thus make its voice heard in the places of power where spatial justice is organized.

En revanche, les possibilités de participation à la vie politique locale ouvertes par la loi de décentralisation promulguée en 1994 sous le nom de « Loi de participation populaire » ont été peu exploitées par les Tacanas. Le contrôle du municipe[10] d’Ixiamas (une des deux sous-divisions administratives de la province) est passé des mains des élites locales à celles des représentants du syndicat de colons (FESPAI - Federación Sindical de Productores Agropecuarios de la Provincia Abel Iturralde) sans que jamais les Tacanas n’investissent ce maillon territorial stratégique (entretiens avec M.H et B.H, officier majeur de mairie et sous-gouverneur, Ixiamas, 12/12/2012). La participation politique indigène semble donc ne pouvoir se déployer qu’à partir de la TCO et non dans un espace municipal multi-ethnique où seulement un tiers de la population se déclare tacana. Ceci explique sans doute l’impossible création du municipe indigène autonome tacana (selon la figure juridique de l’Autonomie indigène originaire paysanne (AIOC - Autonomía Indígena Originaria Campesina)[11], dont le centre aurait été Tumupasa. Malgré la volonté du maire de Tumupasa (J.T., 1/10/2012), un projet d’autonomie politique en dehors du cadre de la TCO semble ne pas pouvoir exister, tandis que le territoire de la TCO ne peut être le point de départ d’un espace autonome[12]. Nous en concluons que dans le cas des Tacanas, le territoire ethnique reste la seule voie pour une participation indigène à la vie politique. L’espace devient alors plus que l’objet de la justice, il en est son moteur.

In contrast, the Tacanas took little advantage of the possibilities of participation in local political life created by decentralisation through the 1994 “Law of Popular Participation” (LPP). Control of Ixiamas municipio[9] (one of the province’s two administrative subdivisions) passed out of the hands of the local elites into those of the representatives of the settlers’ union (FESPAI – Federación Sindical de Productores Agropecuarios de la Provincia Abel Iturralde), without the Tacanas’ involvement in this strategic territorial link (interviews with M.H and B.H, senior town hall official and deputy governor, Ixiamas, 12/12/2012). It would seem, therefore, that indigenous political participation could only emanate from the TCO and not from a multi-ethnic municipal space where only a third of the population called itself Tacana. This probably explains the impossibility of creating an autonomous indigenous Tacana municipio (using the legal status of Peasant Original Indigenous Autonomy or AIOC),[10] which would have been centred in Tumupasa. Despite the wishes of the Mayor of Tumupasa (J.T., 1/10/2012), it would seem that a plan for political autonomy could not exist outside the framework of the TCO, whereas the territory of the TCO could not be the starting point for an autonomous area.[11] From this, we conclude that in the case of the Tacanas, ethnic territory remains the only route to indigenous participation in political life, in which case, space becomes more than the object of justice – it is the engine of justice.

Une justice spatiale ambivalente dans ses effets, en terme de reconnaissance

A spatial justice with ambivalent effects on recognition

Équité dans la distribution foncière, reconnaissance identitaire et participation : la justice spatiale qui se déploie en Amazonie bolivienne depuis les années 1990 semble complète. Pour autant, elle n’est pas sans contradictions, notamment en ce qui concerne la reconnaissance culturelle.

Equity in land distribution, recognition of identity, and participation: the spatial justice that has been implemented in the Bolivian Amazon since the 1990s seems complete. Yet it is not without contradictions, especially with regard to cultural recognition.

La reconnaissance culturelle, levier de justice… ou d’injustice pour les exclus de l’autochtonie

Cultural recognition, a lever of justice… or injustice for those excluded from indigenous status

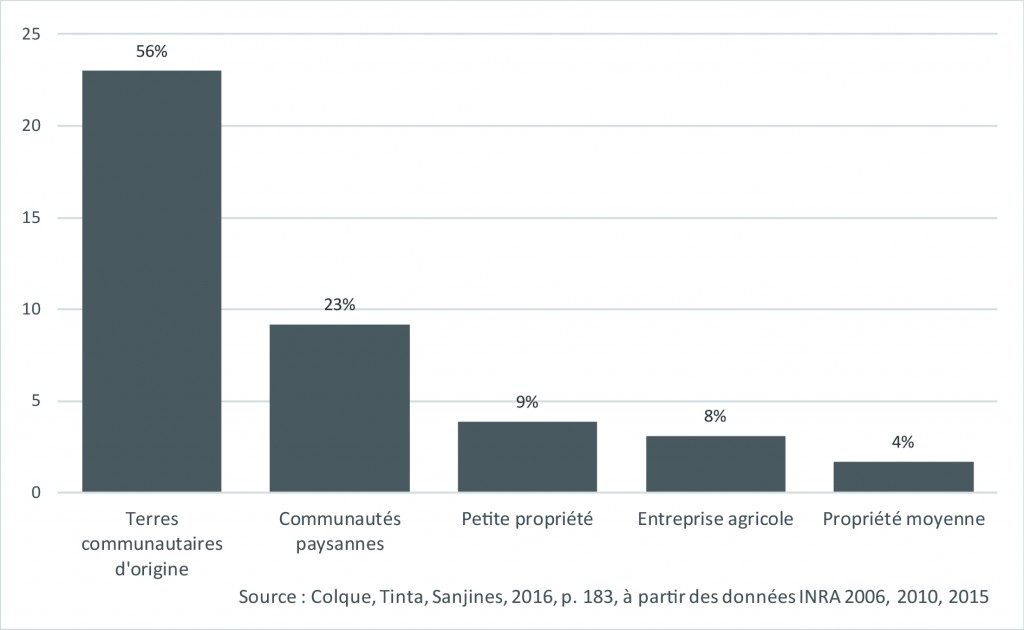

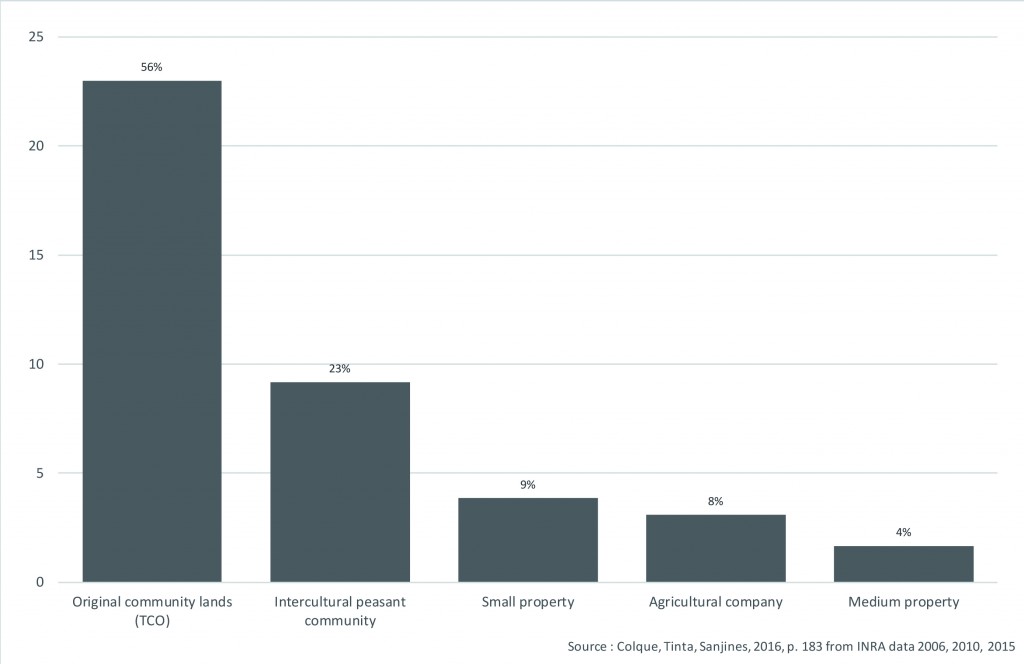

Les premières études sur la justice environnementale ont montré à quel point le facteur ethnique, ou racial dans le cas des États-Unis pouvait être discriminant et produire de l’injustice (Bullard, 1999 ; Walker, 2009). En réponse à cette prise de conscience, les procédures de réparation lancées en Bolivie au milieu des années 1990 ont, au contraire, mobilisé la catégorie indigène dans un sens de discrimination positive. Cela a ouvert la voie à des réparations spectaculaires en termes de territoire concédé aux peuples indigènes. Sur les quelques 40,8 millions d’ha octroyés entre 1996 et 2014, plus de la moitié (23 millions d’ha) l’ont été dans le cadre de TCO (figure 3).

The first studies in environmental justice showed to what extent the ethnic factor, or the racial factor in the case of the US, could be discriminatory and generate injustice (Bullard, 1999; Walker, 2009). In recognition of this, the reparation procedures begun in Bolivia in the mid-1990s instead employed the indigenous category as a means of positive discrimination. This opened the door to spectacular reparations in terms of the allocation of land to indigenous peoples. Of the some 40.8 million ha granted between 1996 and 2014, more than half (23 million ha) were allocated within the framework of TCOs (Figure 3).

Figure 3 : Répartition des terres titrées entre 1996 et 2014 en millions d'ha

Figure 3: Distribution of land titles between 1996 and 2014 in millions of hectares

Revers de la médaille, le critère ethnique, lorsqu’il est utilisé dans les procédures de réparation par le territoire, peut aussi devenir un facteur d’exclusion pour les populations qui ne se définissent pas explicitement par leur ethnicité. Ainsi, dans le Norte La Paz, alors que les familles des communautés de colons n’ont reçu que 50 ha chacune, les 113 familles de la TCO Tacanas se sont partagé 400’000 ha (Viceministerio de Tierras, 2010). Aujourd’hui, l’attribution de ce vaste territoire n’est plus remise en question par les colons. Ceux-ci ont en revanche intégré la relation entre identité indigène et attribution de grandes quantités de terres, et souhaitent la faire jouer en leur faveur. Le contexte s’y prête, puisque dans le Norte La Paz, les terres fiscales qui restent à distribuer dépassent 1,2 millions d’ha (Corz, 2014). Les familles des colons demandent qu’elles leur soient attribuées : « Au moment de la régularisation foncière, nos enfants avaient 8-10 ans. Maintenant ils sont jeunes. Ces terres sont pour eux » (F.D, Secrétaire général de la FESPAI, Ixiamas, 1/05/2013). Pour donner davantage de poids à leur requête, et faire valoir pour leur compte la relation entre reconnaissance indigène et réparation, ces colons originaires des Andes réinvestissent la catégorie indigène. Ainsi, depuis quelques années, ils se qualifient d’« interculturels » pour souligner leur autochtonie et se défaire de la catégorie stigmatisante de colons qui porte la marque de l’extra-territorialité et risque de les exclure du partage des terres. Car, « c’est une triste ironie. [En raison du terme de colons], nous sommes comme des étrangers dans notre propre pays » écrit le syndicat national des interculturels (C.S.C.I.B, 2013). Et de fait, dans ces communautés, l’identité indigène est forte. La plupart des femmes parlent l’aymara ou le quechua, rarement le castillan, les familles sont regroupées dans des quartiers qui portent le nom de leur province ou de leur communauté andine d’origine, et l’alimentation, les outils et les techniques sont déterminés par une culture andine vivace.

The other side of the coin is that the ethnic criterion, when used in reparation procedures based on territory, can also become a factor of exclusion for populations not explicitly defined by their ethnicity. In Norte La Paz, for example, whereas the families of the settler communities received only 50 ha each, the 113 families in the Tacana TCO shared 400,000 ha between them (Viceministerio de Tierras, 2010). Today, the settlers no longer challenge the allocation of this huge area. However, they have recognised the connection between indigenous identity and the grant of large quantities of land, and are keen to turn it to their advantage. The conditions are favourable, since in Norte La Paz more than 1.2 million ha of fiscal land still remains to be distributed (Corz, 2014), which the settler families are asking to be allocated: “At the time of the land regularisation, our children were 8 to 10 years old. Now they are young adults. These lands are for them.” (F.D, Secretary-General of the FESPAI, Ixiamas, 1/05/2013). To lend more weight to their request, and to assert the connection between indigenous recognition and reparation on their own behalf, these settlers from the Andes are seeking to join the category of indigenous. For example, in recent years they have begun to describe themselves as “intercultural” in order to highlight their indigenous status and to break away from the stigma of the settler category, which carries the stamp of extra-territoriality and the risk of exclusion from a share in the land. Because “it is a sad irony. [On account of the term settler], we are like foreigners in our own country” writes the National Union of Interculturals (C.S.C.I.B, 2013). And, in fact, indigenous identity is strong in these communities. Most of the women speak Aymara or Quechua, rarely Castilian, the families gather in neighbourhoods that bear the name of their province or their original Andean community, and the diet, tools and techniques are determined by a lively Andean culture.

Mais souligner cette identité ne suffit pas, car la loi INRA stipule que pour obtenir de grandes superficies de terres, en plus d’être indigène, il faut être originaire de la région. Conscients de cette condition suspensive qui menace de les exclure, les interculturels évoquent, outre leur identité indigène, leur enracinement dans le Norte La Paz où ils sont installés depuis souvent plus de 30 ans. « Nous sommes indigènes et tous frères, originaires de la province Abel Iturralde [Norte La Paz] (...). [Le Vice Ministère des terres] ne répond pas à notre demande de terres, alors qu’il fait venir des frères de l’Occident [des Andes] pour leur distribuer des terres » (D.V, dirigeant FESPAI, 10/09/2013). Par ailleurs, le tournant foncier insufflé par Evo Morales se traduit, même en l’absence de nouvelle loi, par la relance de la colonisation agraire par des colons andins. Face aux nouveaux venus, et contre eux, les interculturels invoquent donc à la fois la reconnaissance indigène et l’enracinement, tout en tordant la catégorie « originaire » pour se rapprocher des peuples d’Amazonie. En novembre 2012, après des années de conflits, les Tacanas et les interculturels ont signé un accord pour demander conjointement les terres d’une concession forestière abandonnée, et en exclure de fait les nouveaux venus (Ströher, 2014).

However, emphasising this identity is not enough, for the INRA Law stipulates as a condition of entitlement to large areas of land that, as well as being indigenous, one must be a native of the region. Aware of this condition precedent that threatens to exclude them, the Interculturals speak, in addition to their indigenous identity, of their rootedness in Norte La Paz, where many have been settled for more than 30 years. “We are indigenous and all brothers, natives of Abel Iturralde province [Norte La Paz] (…). [The Deputy-Minister for Land] does not respond to our request for land, whereas he brings brothers from the Occidente [the Andean region] and distributes land to them” (D.V, leader FESPAI, 10/09/2013). Moreover, the turnaround in land policy instigated by Evo Morales is reflected, even in the absence of a new law, in the revival of agrarian settlement by Andean settlers. In response and opposition to the newcomers, therefore, the Interculturals cite both indigenous recognition and rootedness, while redefining the “native” category to highlight their similarity to the peoples of the Amazon. In November 2012, after years of conflict, the Tacanas and the Interculturals signed an agreement to make a joint application for land on an abandoned forestry concession, thereby de facto excluding the newcomers (Ströher, 2014).

Malgré ce repositionnement, les interculturels sont souvent écartés de la catégorie « indigène originaire », comme dans le cas du fond de compensation de la Banque Interaméricaine de développement et de la Banque Mondiale, destiné à pallier les effets de la construction de la route San Buenaventura – Ixiamas (Carte 3). Ce fond, estimé à 1 million de dollars, a été destiné exclusivement aux Tacanas, ce que les interculturels ressentent comme une profonde injustice. Un dirigeant de leur syndicat me rappelait que seulement 20% des communautés affectées par la route sont indigènes (M.H, dirigeant FESPPAI, Ixiamas, 10/09/2013).

Despite this repositioning, the Interculturals are often omitted from the “indigenous native” category, as in the case of the Inter-American Development Bank and World Bank compensation fund intended to mitigate the effects of the construction of the San Buenaventura-Ixiamas road (figure 6). This fund, estimated at 1 million dollars, was earmarked exclusively for the Tacanas, which the Interculturals resent as profoundly unjust. A leader of their union reminded me that only 20% of the communities affected by the road are indigenous (M.H, leader FESPPAI, Ixiamas, 10/09/2013).

Carte 3 : Répartition des communautés indigènes tacanas (CIPTA) et des communautés interculturelles (FESPAI) le long de la nouvelle route San Buenaventura – Ixiamas

Map 3: Distribution of the Tacana indigenous communities (CIPTA) and the Intercultural communities (FESPAI) along the new San Buenaventura-Ixiamas road

Des Indiens aux peuples indigènes : lorsque la reconnaissance de l’autochtonie ne fait pas justice

From Indians to indigenous peoples: when recognition of indigenousness does no justice

La relation entre justice et reconnaissance doit aussi être évaluée à partir d’une analyse sémiologique et politique de la catégorie indigène, car son contenu peut parfois être source d’injustices. Ce constat est ancien. En Bolivie, comme dans les autres pays andins, la catégorisation ethnique des peuples indigènes des Basses Terres a initialement été imposée de l’extérieur pour justifier la dépossession foncière. Les « Indiens sauvages », tels qu’ils sont mentionnés sur la première carte nationale du pays de 1859, renvoient à une représentation de la société créole des Andes. La « sauvagerie » instaure l’altérité des Indiens et justifie le projet national de conquête des Basses Terres, espace de frontière où la « civilisation » doit avancer pour écrire l’histoire nationale (Perrier Bruslé, 2007). La construction de l’identité indigène par la société métisse justifie la dépossession. De la même façon, Michael Taussig, à propos du shamanisme en Amazonie colombienne à l’époque du boom du caoutchouc, montre que la sauvagerie des Indiens, produite par l’imaginaire colonial, a enclenché un cycle de violence réciproque (Taussig, 1987). La catégorisation ethnique sert donc l’entreprise de domination coloniale, ce que de nombreux auteurs postcoloniaux ont montré dans d’autres contextes que la Bolivie (Said, 1978 ; Spivak, 1987 ; Tsing, 2000).

The relation between justice and recognition must also be assessed in the light of a semiological and political analysis of the indigenous classification, since its content can sometimes be a source of injustices. This is not a new observation. In Bolivia, as in the other Andean countries, the ethnic classification of the indigenous peoples of the Lowlands was originally imposed from outside to justify land dispossession. “Indian savages”, as they were described on the first national map of the country in 1859, referred to a representation of the Creole society of the Andes. “Savagery” defined the otherness of the Indians and justified the national plan to conquer the Lowlands, a frontier space where “civilisation” must advance in in the interests of national history (Perrier Bruslé, 2007). The construction of indigenous identity by mixed-race society justified dispossession. In the same way, writing about shamanism in the Colombian Amazon at the time of the rubber boom, Michael Taussig shows how the savagery of the Indians was a product of colonial imagination and triggered a cycle of reciprocal violence (Taussig, 1987). Ethnic classification thus served the enterprise of colonial domination, which numerous postcolonial authors have demonstrated in contexts other than Bolivia (Said, 1978; Spivak, 1987; Tsing, 2000).

En Amazonie bolivienne, la construction exogène de l’ethnicité continue de nos jours. Après les Pères Franciscains qui ont fixé les contours de l’identité tacana, et après les patrons du caoutchouc qui en ont fait des travailleurs exploités, sont venues les Églises et les ONG de l’époque néolibérale. Ces dernières ont aidé les peuples indigènes à obtenir des terres dans le cadre de la loi INRA. Les Tacanas ont été soutenus par Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). L’ONG a recruté des chercheurs en sciences sociales qui ont organisé des ateliers, mis en forme les demandes de terres, puis établi des plans de gestion de la TCO. Ce faisant, ils ont peu à peu fixé les contours d’une identité tacana, comme cela s’est pratiqué dans d’autres régions de Bolivie (Herrera Saramiento, 2009 ; Lavaud, 2007). Or, cette alliance entre ONG et peuples indigènes, si elle a permis d’incontestables avancées en termes de récupération foncière, a souvent conduit à la formulation d’une identité formatée depuis l’extérieur. La littérature produite pendant cette période en témoigne : quels que soient les peuples concernés, les mêmes références à une cosmogonie indienne simplifiée, à des modes de vies traditionnels, et à un rapport privilégié à l’environnement égrènent les rapports des experts, co-signés par les ONG et les directoires indigènes. En outre, les similitudes qui s’y dessinent entre les différents peuples de l’Oriente, ainsi que les points communs avec les cultures indigènes nord-américaines (voir Whiteman, 2009), laissent suspecter une relative standardisation de l’identité indigène.

In the Bolivian Amazon, the construction of ethnicity by outsiders continues to the present day. After the Franciscan monks, who defined the outlines of Tacana identity, and after the rubber bosses who turned them into exploited workers, came the churches and NGOs of the neoliberal era, who helped the indigenous peoples to obtain land within the framework of the INRA Law. The Tacanas were supported by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), which recruited social science researchers to organise workshops, formulated the applications for land, then established management plans for the TCO. In so doing, they gradually defined the contours of a Tacana identity, as happened in other regions of Bolivia (Herrera Saramiento, 2009; Lavaud, 2007). However, this alliance between NGO and indigenous peoples, while it produced indisputable advances in terms of land recovery, has often led to the formulation of an identity from outside. The literature of this period bears witness to the process: whatever peoples were concerned, the same references to a simplified Indian cosmogony, to traditional ways of life, and to a special relationship with the environment, run through the reports of the experts, co-signed by the NGOs and the indigenous administrative structures. In addition, the similarities that emerge between the different peoples of the Oriente, and the commonalities with indigenous North American cultures (see Whiteman, 2009), suggest a relative homogenisation of indigenous identity.

Cette imposition d’une identité formatée par des acteurs extérieurs s’est avérée d’autant plus problématique qu’au cours des dernières décennies, ONG et peuples indigènes se sont battus pour une justice environnementale aux objectifs divergents. Si les premiers ont lutté pour la forêt, en tant que patrimoine mondial de l’humanité, les seconds ont défendu leur territoire ancestral. C’est ainsi que la lutte, en changeant d’espace d’action politique, a aussi changé d’objet. Cela a été lourd de conséquences pour les peuples indigènes de l’Oriente. En effet, l’importance du métissage dans la constitution de leurs cultures n’a pas été prise en compte par les ONG qui ont souvent réduit la spécificité indigène à un rapport privilégié à l’environnement. La reconnaissance culturelle, en somme, a conduit les ONG écologistes à imposer une vision partielle de l’autochtonie, comme cela s’est vu ailleurs (Martin et al., 2014). Les Églises évangéliques, institutions qui, à l’instar des ONG, inscrivent leur action à l’échelle globale, ont aussi contribué à instrumentaliser l’identité indigène à des fins propres, comme l’avaient fait avant eux les pères missionnaires du XVIIème siècle. J. A. T., cet instituteur déjà cité, relate comment la renaissance culturelle tacana a servi l’objectif global de la diffusion de la foi chrétienne : « C’est un institut linguistique à Tumichuco qui a fait renaître la langue tacana dans les années 1960. Il s’appelait l’Institut d’été [Instituto Lingüístico de Verano]. Ils ont travaillé pour sauver la langue et avaient aussi un message religieux fort. Ils voulaient dans le même temps conquérir des disciples pour les évangéliser.» (J. A.T., San Buenaventura, 29/04/2013).

This imposition of an identity constructed by external actors has proved particularly problematic in recent decades, as NGOs and indigenous peoples have fought for an environmental justice to different ends. While the former were fighting for the forest, as a world heritage of humanity, the latter were defending their ancestral lands. The result is that, as the space of political action changed, the goal of the struggle changed with it. This has had major consequences for the indigenous peoples of the Bolivian Oriente. Indeed, the NGOs failed to recognise the importance of an ethnic mix in the constitution of their cultures, often reducing the specificity of indigenousness to a special relationship with the environment. In short, cultural recognition prompted ecological NGOs to impose a partial vision of indigenousness, as has been seen elsewhere (Martin et al., 2014). The evangelical churches, institutions which – like the NGOs – operate at a global scale, have also contributed to the exploitation of indigenous identity for their own ends, as the 17th-century missionaries did before them. J.A.T., the already mentioned school teacher, relates how the Tacana cultural renaissance served the global goal of spreading the Christian faith: “It was a language institute in Tumichuco which revived the Tacana language in the 1960s. It was called the Institute of Summer [Instituto Lingüístico de Verano, NDT]. They worked to save the language and also had a strong religious message. Their goal was at the same time to attract and convert disciples.” (J. A.T., San Buenaventura, 29/04/2013).

Dans le Norte La Paz, les relations entre ONG et peuples indigènes se sont détériorées à partir de 2005. Faut-il y voir un désir d’indépendance de la part des peuples indigènes et le rejet de catégorisations ethniques ne faisant pas justice parce qu’en partie imposées de l’extérieur ? Ou encore, la déception engendrée par un multiculturalisme néolibéral qui a donné des droits culturels sans contrepartie forte en terme d’autonomie (Hale, 2005) ? Dans le cas des Tacanas, l’alliance historique entre ceux-ci et WCS a été mise à mal à partir de 2010. Un dirigeant du directoire tacana explique ce divorce par des contentieux financiers auxquels s’ajoute la volonté d’indépendance : « Nous voulons couper les liens avec toutes les ONG et chercher notre propre force » (A.T., Tumupasa, 30/04/2013). La directrice de l’institut culturel tacana évoque quant à elle « des menaces [qui] ont été formulées par les ONG, liées à leur politique et leur manière d’être. Nous y avons mis un frein. Ici, les ONG doivent s’adapter à ce que le peuple tacana décide » (N.C., Tumupasa, 30/04/2013). Le rejet des ONG témoigne autant d’un désir d’autonomie que du refus d’une reconnaissance culturelle qui ne ferait pas justice parce que imposée de l’extérieur ; standardisée, elle serait au final pétrifiée, comme « un socle stable et hors du temps » (Tsing, 2009, p. 283).

In Norte La Paz, relations between NGOs and indigenous peoples deteriorated after 2005. Should we see this as a sign of a desire for independence on the part of the indigenous peoples and the rejection of ethnic categories that failed to produce justice because they were partly imposed from outside? Or else a sign of disappointment in a neoliberal multiculturalism that bestowed cultural rights with no significant counterpart in terms of self-government (Hale, 2005)? In the case of the Tacanas, the historical alliance with the WCS began to turn sour after 2010. A leader of the Tacana administration explains this divorce as being a result of financial disputes combined with the desire for independence: “We want to cut the links with all the NGOs and find our own strengths” (A.T., Tumupasa, 30/04/2013). For her part, the Director of the Tacana Cultural Institute refers to “threats formulated by the NGOs, linked with their policy and way of doing things. We put a stop to it. Here, the NGOs have to adapt to what the Tacana people decides” (N.C., Tumupasa, 30/04/2013). The rejection of the NGOs testifies as much to a desire for autonomy as to the refusal of a cultural recognition that does not bring justice, because imposed from outside; standardised from the start, it eventually becomes frozen, like “an imagined bedrock of out-of-time stability” (Tsing, 2009, p. 283).

Justice distributive versus justice par la reconnaissance

Distributive justice versus justice through recognition