Introduction

Introduction

Longtemps considérée comme un « problème urbain », la favela, est couramment regardée comme une catégorie à part, comme un espace autre, représenté en miroir inversé face à la ville, tout comme ses habitants, souvent victimes d'un imaginaire social stigmatisant. Elle s’est pourtant constituée comme une solution de logement pour des milliers de familles privées de l'accès au foncier urbain formel, dans un contexte d'industrialisation et d'urbanisation accélérées. Les favelas sont ainsi le produit d’une inégalité sociale accentuée dans les métropoles brésiliennes, où richesse et pauvreté sont dans une relation ambigüe, faite à la fois de proximité territoriale et de distance sociale (Valladares, 2005). Elles sont le support d’un processus historique de marginalisation sous de multiples facettes : sociale, économique, politique, juridique et qui s’exprime par des seuils physiques et symboliques formant des frontières entre le dedans et le dehors. Dans ce contexte de relégation, sont nés des mécanismes d'appropriation territoriale, où s'expriment des rapports de pouvoirs et de contrôle à travers des dispositifs autoritaires et le relais de différents systèmes de répression, depuis les dictatures à la territorialisation des groupes criminels en passant par les abus de pouvoir des policiers. Dans quelle mesure peut-on parler d’espace autoritaire, au Brésil et plus particulièrement concernant les favelas ? Il nous faut alors aller au-delà de la conception spatiale en considérant les interactions entre l’espace physique, l’espace social et l’espace socio-cognitif. L'espace peut ainsi apparaître comme un objet de contrôle et donc de domination, de puissance et d’autoritarisme. Le territoire, avec sa double dimension, une nature géographique et un contenu idéologique traduit à la fois un mode de découpage et un mode de contrôle de l’espace. Le territoire possède ainsi une dimension politique illustrant la nature intentionnelle de sa production. Si comme l’affirme Olivier Dabène «tout phénomène politique est potentiellement autoritaire » (Dabène, 2008, p. 8) alors, la production de l’espace est autoritaire puisque l’espace est par essence politique. Le territoire produit lui-même des effets autoritaires notamment «l'effet de lieu » qui résulte des représentations que nous avons d'un territoire bien identifié dans nos pratiques sociales et qui impose à certains territoires une image négative, ce qui est entre autres, le cas des favelas à Rio de Janeiro. Les représentations territorialisées produites par l’effet de lieu des favelas cristallisent les stigmatisations et la fragmentation de la ville.

Favelas, which for a long time were considered as an urban problem, are currently viewed as a separate category or space, a reversed mirror image of the city, with favela residents often being the victims of social stigma as a result. Yet, in a context of accelerated industrialisation and urbanisation, favelas represented a housing solution for thousands of families deprived of access to formal land in the city. As such, they are the product of social inequality which is emphasised even more in Brazilian metropolises, where wealth and poverty form an ambiguous relationship made up of territorial proximity and social distance (Valladares, 2005). Favelas are the medium for a historical and multi-facetted marginalisation process, be it social, economic, political or legal, which is expressed via physical and symbolic thresholds forming boundaries between the inside and the outside. In this context of relegation, there came mechanisms for territorial appropriation, giving rise to power and control relations through authoritarian systems and the relay of different repressive systems, from dictatorships to the territorialisation of criminal groups, via the abuse of power of the police force. To what extent can we speak of authoritarian space in Brazil, and more particularly as regards favelas? For this we need to go beyond the conception of space, by taking into consideration interactions between physical space, social space and socio-cognitive space. Space can then appear as an object of control and therefore domination, power and authoritarianism. The territory, with its double dimension, a geographic nature and an ideological content, reflects a division mode as well as a control mode of space. The territory has a political dimension which illustrates the intentional nature of its production. If, as claimed by Olivier Dabène, “any political phenomenon is potentially authoritarian” (Dabène, 2008, p. 8), then the production of space is authoritarian since space is essentially political. The territory itself produces authoritarian effects, “the place effect” in particular which results from the representations we have about a territory which is well identified in our social practices, and which imposes a negative image upon certain territories, which is the case of the favelas in Rio de Janeiro, among others. The territorialised representations produced by the place effect of the favelas, crystallise the stigmatisations and fragmentation of the city.

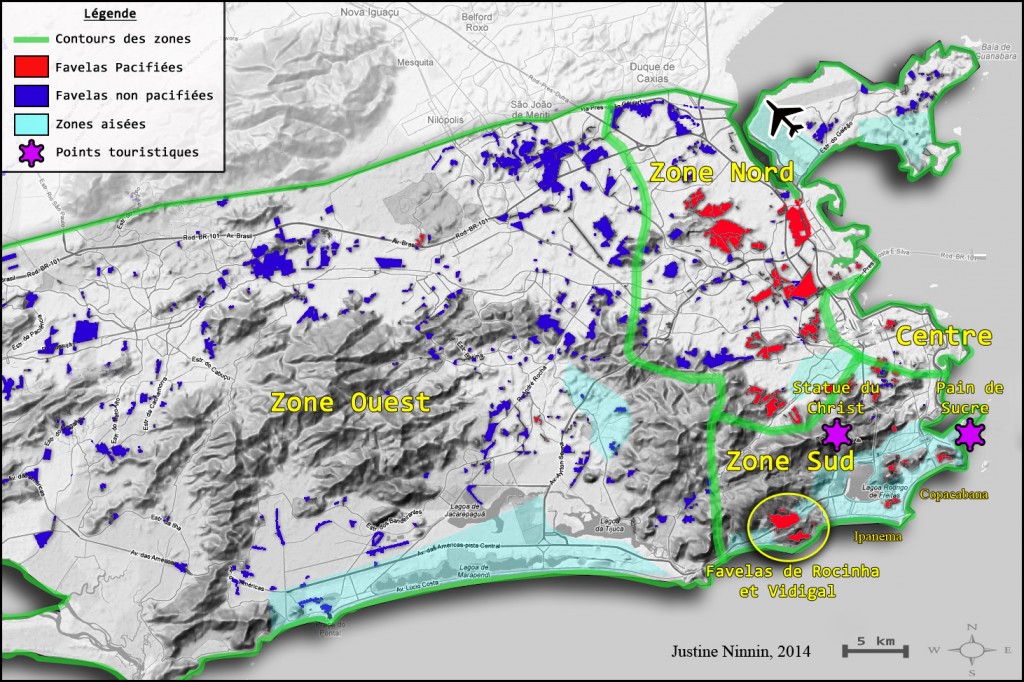

Le contexte historique brésilien nous permet d’identifier des enclaves autoritaires, où la transition entre régime autoritaire et régime démocratique passe par des situations de chevauchements. «L’héritage autoritaire brésilien, encore perceptible au début du XXIe siècle, a été façonné par le temps long de la société coloniale, et par le temps court de deux dictatures au XXe siècle (1930-1945 et 1964-1985)» (Dabène, 2008, p. 98). L'autoritarisme serait “socialement implanté” avec la prégnance de la violence dans les rapports sociaux, le manque de respect des droits civils et les «micro-despotismes» de la vie quotidienne (violence conjugale et domestique, justice privée, abus sexuels…) (Pinheiro, 2000). C'est à l’échelle locale que cet article analyse les relations entre espace et pouvoir dans les favelas de Rio de Janeiro. Au travers d'un processus historique de mises à distance de la favela du droit à la ville et même du droit de la ville, on observe encore à l'heure actuelle des rémanences autoritaires sur ces territoires. Toutefois, depuis quelques années, les politiques publiques tentent de mettre l’accent sur la nécessaire reconnaissance de ce qu'il y a de commun et ce qu'il y a de particulier dans chaque favela de la ville. Les recherches présentées ici portent sur la nouvelle politique de sécurité : «la pacification» ainsi que les politiques dites d’urbanisation des favelas et les actions de développement économique et social. Selon l’Institut Perreira Passos, 1 443 773 personnes vivent dans les 1035 favelas de la ville de Rio de Janeiro qui accueillent donc près de 23% de la population (Cavallieri & Via, 2012). Depuis 2008, près de 200 favelas ont été pacifiées avec l’installation de 37 Unités de Police de Pacification (UPP). Mes recherches privilégient une approche ethnographique dans deux favelas situées dans la zone sud de Rio de Janeiro, la plus riche et la plus touristique : Rocinha, qui compte environ 100 000 habitants, et Vidigal, environ 10 000, où j'ai habité, réalisé des entretiens, et participé à des activités communautaires[1].

Through the historical context of Brazil, we can identify authoritarian enclaves, where the transition from authoritarian to democratic regimes goes through overlapping situations. “The Brazilian authoritarian heritage which is still perceptible at the beginning of the 21st century, was fashioned over time by the long term colonial society and the two short term dictatorships of the 20th century (1930-1945 and 1964-1985)” (Dabène, 2008, p. 98). Authoritarianism would have been “socially established” with the pregnance of violence in the social relations, the lack of respect of civil rights and the “micro-tyranny” of everyday life (conjugal and domestic violence, private justice, sexual abuse etc.) (Pinheiro, 2000). It is at the local level that this article analyses the relationships between space and power in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. Through a historical process whereby favelas were kept away from the right to – and even of – the city, today we can still observe authoritarian persistence on these territories. However, for a few years now, public policies have been trying to emphasise the necessary recognition of what is common as well as specific in each favela of the city. The research presented here concerns the new security policy: “the pacification” and so-called urbanisation policies of the favelas, as well as economic and social development interventions. According to the Perreira Passos Institute, 1 443 773 people live in the 1 035 favelas of Rio de Janeiro, i.e. almost 23% of the population (Cavallieri & Via, 2012). Since 2008, close to 200 favelas have been pacified through the establishment of 37 Police Pacification Units (UPP). My research favours an ethnographic approach in two favelas located in the south of Rio de Janeiro, which is the wealthiest and most touristic area of the city. These are Rocinha which has around 100 000 residents, and Vidigal with around 10 000, where I lived and carried out interviews and took part in community activities[1].

Carte 1 : Carte de Rio de Janeiro, favelas pacifiées et localisation de Rocinha et Vidigal, Justine Ninnin, 2014

Map 1: Map of Rio de Janeiro, pacified favelas and location of Rocinha and Vidigal, Justine Ninnin, 2014

La première partie de l’article analyse la cristallisation des rémanences autoritaires dans les favelas, en observant les pouvoirs autoritaires qui y sont exercés par différents acteurs comme les médias, l'État ou encore les groupes criminels. La deuxième partie s’interroge sur les effets d’intégration des actions publiques récentes notamment concernant le droit à la ville et la justice socio-spatiale. Enfin, la dernière partie aborde les possibilités de mobilisation des habitants.

The first part of the article analyses the crystallisation of authoritarian persistence in favelas, by observing the authoritarian powers exercised by different actors such as the media, the State or, still, criminal groups. The second part questions the effects of including recent public interventions, those concerning the right to the city and socio-spatial justice in particular. Finally, the last part examines the mobilisation potential of residents.

Les favelas : des espaces autoritaires aux marges de la ville ?

Favelas: Authoritarian Spaces at the Margins of the City?

Au regard des dynamiques territoriales du pouvoir, l’espace, dans sa dimension politique et sociale, est perçu comme un objet de contrôle. Nous définissons l’espace autoritaire comme un territoire où les libertés individuelles sont limitées et où, dans la pratique, la souveraineté et les droits des individus sont minimisés par rapport au reste de la société. « Hétérotopies » – pour reprendre le terme de Foucault – les favelas seraient «des sortes de lieux qui sont hors de tous les lieux» (Foucault, 1994, p. 756), des «espaces d’exception mis à l’écart du monde commun, mais encore sous contrôle» (Agier, 2008, p. 222). Dans une logique de mise à l’écart et de production de frontières, à la fois par les politiques publiques, mais aussi par l’opinion publique, les favelas sont considérées comme périphériques ou marginales par rapport à une référence urbaine idéelle. Les politiques d’exclusion suscitent la création «d’espaces d’extraterritorialité» régis par des «lois d’exception» (Birman & Souty, 2013). Sur ces espaces autoritaires, on retrouve alors ce qu’Agamben définit comme l’état d’exception, c’est-à-dire un espace où la norme et le droit valent, mais ne s'appliquent pas ou que partiellement (Agamben, 2003).

From the point of view of the territorial dynamics of power, space, in its political and social dimension, is perceived as an object of control. We define authoritarian space as a territory where individual liberties are limited and where, in practice, sovereignty and the rights of individuals are minimised compared to the rest of society. As heterotopies – according to Foucault – favelas are “kinds of places that are outside of all places” (Foucault, 1994, p. 756), “spaces of exception kept away from the common world, but still under control” (Agier, 2008, p. 222). The fact that favelas are kept in the background and boundaries are created through public policies and public opinion, favelas are considered as peripheral or marginal compared to an ideal urban reference. Exclusion policies provoke the creation of “spaces of extraterritoriality” governed by “rules of exception” (Birman & Souty, 2013). On these authoritarian spaces, we find what Agamben defines as the state of exception, i.e. a space where norms and rights are valid, but do not or only partially apply (Agamben, 2003).

Le rôle de l’opinion publique et des médias dans la production d’espaces autoritaires

The Role of Public Opinion and the Media in the Production of Authoritarian Spaces

Dans l’introduction de l’ouvrage Um Seculo de Favela, Alvito et Zaluar (1998) soulignent que la littérature sur les favelas a contribué, tout comme la presse et l’opinion publique, à créer une «mythologie urbaine». À Rio de Janeiro, la pauvreté a longtemps été vue comme un vice et les «favelados» comme des individus vivant «hors de la société formelle et sur son dos» (Goirand, 2000, p. 84). Les favelas deviennent rapidement un problème urbain et sont pointées du doigt comme lieu de regroupement de la marginalité, de l’insalubrité et des classes dangereuses, responsables des « maux urbains ». Avec la prolifération des groupes criminels armés, l’expansion du narcotrafic et l’augmentation des violences urbaines dans les années 1980, les représentations sociales associent naturellement pauvreté, criminalité, insécurité et favela, les médias contribuant largement à véhiculer un symbolisme négatif à travers la fascination télévisuelle et la mise en spectacle de la violence. Il s’agit d’une territorialisation de la pauvreté et de la violence ainsi que d’une criminalisation de la misère, mais pauvreté et crime sont largement présents en dehors des favelas. En effet, les favelas ont connu un processus de production de frontières fictives. Bien qu’elles aient une visibilité dans l’espace urbain qui en fait des territoires spécifiques, elles ne se ressemblent pas toutes pour autant, et sont des territoires complexes, support d’une grande diversité. Il n’y a « ni homogénéité, ni spécificité, ni unité entre elles, ni même en leur sein pour les grandes » (Valladares, 2006, p. 161). Loin de vivre dans des enclaves de la ville fonctionnant de manière isolée et autonome, une grande partie des habitants est insérée dans le tissu urbain (emplois dans les zones aisées, relations amicales et familiales en dehors de la favela, etc.). Des transformations internes significatives ont opéré notamment concernant les modes d’occupation, les infrastructures et équipements. Auparavant essentiellement spontanées et précaires, les favelas ont rapidement connu une complexification du bâti avec l’apparition d’immeubles. La population elle-même s’est diversifiée, laissant apparaître notamment ce que Machado da Silva (1967) appelle la «bourgeoisie favelada» qui se compose d’individus ayant plus de ressources (capital social, culturel, politique et économique). La favela, est alors loin de ce que Wacquant nomme « hyperghetto », soit, un espace comprenant « presqu’exclusivement les secteurs les plus vulnérables et les plus marginalisés de la communauté noire » (Wacquant, 2006, p. 111). Toutefois, le rapport de force entre marginalisation et intégration, souligne à la fois la reconnaissance de cette diversité et des richesses internes, mais aussi une mise à distance de ces territoires, dits d’exception, encore dénommés aujourd’hui « agglomérats sous-normaux» par l’IBGE. Les stigmatisations ont alors en partie servi à justifier une planification urbaine autoritaire concernant ces territoires (destruction et/ou confinement) ainsi qu’une politique de sécurité répressive mêlant violence policière et abus d’autorité envers leurs habitants.

In the introduction of their book Um Seculo de Favela, Alvito and Zaluar (1998) highlight the fact that the literature on favelas contributed to creating an “urban mythology”, as did the press and public opinion. In Rio de Janeiro, poverty was for a long time perceived as a vice, and “favelados” as individuals living “outside formal society and at its expense” (Goirand, 2000, p. 84). Favelas then quickly became an urban problem and were denounced as grouping places for marginality, insalubrity and dangerous classes responsible for “urban ills”. With the proliferation of armed criminal groups, the expansion of drug trafficking and the increase in urban violence in the 1980s, social representations have naturally been associating poverty, criminality and insecurity with favelas. In this regard, the media have been widely contributing to conveying a negative image of favelas, through TV programmes reporting on violence, resulting in the territorialisation of poverty and violence, and in the criminalisation of destitution, although poverty and crime are very much present outside favelas. Indeed, favelas have experienced a process of fictive boundary production. Although their visibility in the urban space makes of them specific territories, it does not mean that they actually all look the same: they represent complex territories and support diversity. There is “neither homogeneity, nor specificity or unity between them, not even within large favelas” (Valladares, 2006, p. 161). Far from living in urban enclaves functioning in isolation and autonomously, many residents are integrated into the urban fabric (employment in well-off areas, friendly and family relations outside the favela, etc.). Significant internal transformations have taken place concerning occupation modes, infrastructure and equipment in particular. While in the past favelas were mainly spontaneous and precarious, their buildings have rapidly become increasingly complex, with the appearance of blocks of flats. The actual population has become more diverse, with the rise in particular of what Machado da Silva (1967) calls the “favela bourgeoisie” which is made up of individuals who have more resources than others (social, cultural, political and economic capital). Favelas are then far from what Wacquant calls “hyperghettos”, i.e. spaces including “almost exclusively the most vulnerable and marginalised sections of the black community” (Wacquant, 2006, p. 111). However, the balance of power between marginalisation and integration highlights not only the recognition of diversity and internal wealth, but also the fact that these so-called territories of exception – still called “subnormal agglomerates” today by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) – are kept at a distance. The fact that favelas are denounced as places of marginalisation partly served to justify the authoritarian urban planning affecting these territories (destruction and/or confinement), as well as the repressive security policy, combining police violence with abuse of power towards favela residents.

Les différents ressorts des actions autoritaires de l’État sur les favelas : planification urbaine, clientélisme et police

The Different Types of Authoritarian State Interventions on Favelas: Urban Planning, Clientelism and Police

Jusque dans les années 1970 de nombreuses campagnes, notamment hygiénistes, ont été menées contre les favelas, perçues comme inesthétiques, insalubres et menaçantes pour la «tranquillité» du reste de la ville, bien que quelques expériences d’aménagement interne des favelas aient eu lieu durant cette période. La réouverture démocratique a progressivement marqué la fin de la politique d’éradication et de relogements massifs et la mise en place de politiques dites d’urbanisation des favelas (Soares Gonçalves, 2010). Le gouvernement Leonel Brizola de 1982, a, par exemple, proposé de transformer les favelas en « quartiers populaires » et distribué certains titres de propriété. La constitution de 1988 prévoit le déplacement seulement dans le cas où les conditions physiques du territoire pourraient engendrer un risque pour les habitants. Les actions des pouvoirs publics dans les favelas se sont amplifiées avec le Plan Directeur de la Ville de Rio de Janeiro de 1992, qui confirme l'implantation d'un programme global d'intégration des favelas à la ville. En 1994, est mis en place le premier grand programme d’urbanisation des favelas : Favela-Bairro, auquel se succédera différentes politiques comme plus récemment le Programme d’Accélération de la Croissance (2007) ou Morar Carioca (2010), qui, à travers des travaux d'infrastructures, la création d'équipements urbains et la régularisation foncière, promeuvent l'intégration et la transformation de la favela en quartier. Avec le processus de consolidation politico-administrative, les favelas affirment leur place dans le paysage urbain. Les pouvoirs publics cherchent toutefois à contenir les favelas en freinant les occupations illégales ainsi que leur expansion horizontale et verticale, au travers de mesures telles que la construction de murs et d’éco-limites. Le contrôle autoritaire de ces espaces par les politiques urbaines n’a toutefois pas empêché une transformation et une consolidation des favelas. Cependant, Soares Gonçalves (2013) parle d’un retour récent des politiques d’éradication des favelas avec des actions «extrêmement violentes et injustes». Les opérations de déplacements forcés se fondent sur différents volets des politiques publiques: les zones à risques, la protection de l'environnement, les travaux d'infrastructures et plus récemment les aménagements dont l’objectif est de mettre l’espace urbain en conformité avec les exigences d'accueil des événements sportifs internationaux.

Up until the 1970s, many campaigns – hygienist campaigns in particular – were led against favelas that were perceived as unsightly, unfit for habitation and threatening the “peace of mind” of the rest of the city, although a few experiments to develop facilities inside favelas had taken place during that period. The State reopening the doors to democracy progressively marked the end of the eradication and massive rehousing policy, and the establishment of so-called favela urbanisation policies (Soares Gonçalves, 2010). The Leonel Brizola government of 1982 did propose for example to transform favelas into “popular suburbs” and distribute title deeds. The 1988 constitution provided for displacement only in the case where a territory’s physical conditions could entail a risk to residents. The interventions of public authorities in favelas became amplified with the Master Plan of the city of Rio de Janeiro in 1992, which confirmed the introduction of a global programme for integrating favelas into the city. In 1994, the first major programme for the urbanisation of favelas was established: Favela-Bairro, which was followed by different policies such as, more recently, the Growth Acceleration Programme (2007) or Morar Carioca (2010) which, through infrastructure works, the creation of urban equipment and land regularisation, promoted the integration and transformation of favelas into suburbs. With the politico-administrative consolidation process, favelas asserted their place in the urban landscape. But the public authorities sought to contain favelas by slowing down illegal occupations as well as their horizontal and vertical expansion, through measures such as the construction of walls and eco-borders. The authoritarian control of these spaces, through urban policies, did not however prevent the transformation and consolidation of favelas. Nonetheless, Soares Gonçalves (2013) spoke of the recent return of policies for the eradication of favelas, by means of “extremely violent and unfair” interventions. Forced displacement operations were based on the different sections of public policies: danger zones, protection of the environment, infrastructure works and, more recently, installation works aiming at ensuring that urban space complies with the requirements for hosting international sporting events.

«L’autoritarisme n’est pas seulement pensé à la marge des démocraties, il est aussi traité en leur cœur» (Dabène, 2008, p. 12). Au Brésil, les comportements électoraux permettent également d’observer ces rémanences autoritaires, par exemple le contrôle clientéliste des suffrages. Héritage de la société patriarcale, exacerbé par les dictatures, le clientélisme se retrouve au niveau local, dans les favelas. Il prend souvent le nom de politique «da bica de agua» (du robinet d’eau) dans le sens où les promesses d’amélioration des conditions de vie (infrastructures, équipements, etc.) portées par les politiciens dans les favelas surgissent très souvent lors des périodes électorales. Les habitants sont ainsi utilisés comme des instruments de régulation électorale. Ce système clientéliste s’appuie sur des hiérarchies internes et les renforce, par exemple les membres des associations de résidents, les propriétaires de compteurs d’énergie ou de commerces. Si l’on peut parler de rémanence autoritaire, les habitants, méfiants à l’égard des politiciens, apprennent néanmoins à s’adapter stratégiquement au système politique et savent en tirer parti (collectivement et/ou individuellement). En situation de concurrence entre politiciens, ils savent qu’ils sont en position de négocier leur vote, ce qui engendre alors une surenchère des actions sociales et des dons (Goirand, 2000).

“Authoritarianism is not only thought out at the margin of democracies, it is also dealt with in their centre” (Dabène, 2008, p. 12). In Brazil, electoral behaviours also made it possible to observe this authoritarian persistence, e.g. the clientelist control of the votes. Inherited from patriarchal society and exacerbated by dictatorships, clientelism is found at the local level, in favelas. It often takes on the name of da bica de agua policy (“the water tap policy”), in the sense that the promises made by politicians in the favelas, with a view to improving living conditions (through infrastructure, equipment, etc.), very often come up during election periods. As such, residents are used as instruments of electoral regulation. This clientelist system relies on internal hierarchies and reinforces them, e.g. the members of residents’ associations, the owners of energy meters or shop owners. While we can talk about authoritarian persistence, the residents who are suspicious of politicians learn nonetheless to adapt strategically to the political system, and know how to take advantage of it (collectively and/or individually). In situations where politicians compete, residents know that they are in a position to negotiate their vote, thereby causing politicians to outdo one another in social interventions and gifts (Goirand, 2000).

Par ailleurs, l’institution policière et ses pratiques abusives, héritées de la dictature, apparaissent également comme une enclave autoritaire au Brésil. La police est imprégnée de la mentalité du régime militaire et fonde ses interventions sur l’idée d’un ennemi intérieur à éliminer (Deluchey, 2003) (Zaluar, 2004). Dans les favelas, les abus d’autorité et l’irrespect des droits sont des attitudes fréquentes de la part des policiers qui souvent ne différencient pas l’habitant «honnête» du bandit (contrôles d’identité et fouilles violentes, arrestations arbitraires, moyens mis en œuvre disproportionnés, usage d’armes, recours à des pratiques vexatoires,…). La violence institutionnelle passe par un «usage illégal, illégitime et indu de la force par l’appareil répressif d’un État» (Daudelin, 1996, p. 97). Se pose la question de l’impunité de certains «homicides» en démocratie, notamment, les «actes de résistance» c’est-à-dire les morts liées à des confrontations des habitants avec les policiers abusant souvent de la justification de légitime défense. Les exécutions extrajudiciaires sont parfois perçues comme un moyen pour se débarrasser des criminels, face à un système judiciaire considéré comme défectueux ; tolérés à la fois par des habitants des quartiers aisés, mais aussi par des habitants de favelas, qui s’ils critiquent fortement les opérations violentes des policiers font la distinction entre la mort d’un habitant innocent et la mort d’un bandit. Par ailleurs, cette même police tire dans certains cas des bénéfices des marchés illégaux, par le biais de la corruption. Il s’est installé dans les favelas un espace où « violence, droit, autorité et puissance se mêlent sans plus pouvoir se différencier et s’auto-légitiment » (Agamben, 2003). À travers un contrôle autoritaire et des opérations ponctuelles extrêmement violentes, l’institution policière a contribué à renforcer le sentiment d’insécurité des habitants de favelas.

Moreover, the police institution and its abusive practices inherited from the dictatorship, also appear as an authoritarian enclave in Brazil. The police force is imbued with the mentality of the military regime and founds its interventions on the idea of an internal enemy that must be eliminated (Deluchey, 2003) (Zaluar, 2004). In favelas, abusing one’s power and failing to observe residents’ rights are frequent attitudes from police officers who often do not differentiate between “honest” residents and gangsters (identity checks and violent searches, arbitrary arrests, disproportionate means being implemented, use of weapons, resorting to harassment…). Institutional violence goes through the “illegal, illegitimate and undue usage of force by the repressive State machinery” (Daudelin, 1996, p. 97). This raises the issue of impunity as far as certain “homicides” are concerned in this democratic country, those resulting from “acts of resistance” in particular, i.e. deaths related to residents confronting the police force, with the latter too often claiming self-defence. Extrajudicial executions are sometimes perceived as a means of getting rid of criminals where the judiciary system is viewed as faulty. Homicides are tolerated by the residents of well-off suburbs, but also by the residents of favelas who, while strongly criticising the violent operations of the police force, do distinguish between the death of an innocent resident and that of a gangster. Moreover, in certain cases, the police force does draw benefits from illegal markets via corruption. Favelas have seen the establishment of a space where “violence, rights, authority and power mix without distinction from one another and self-legitimate” (Agamben, 2003). Through authoritarian control and extremely violent sporadic operations, the police institution has contributed to reinforcing the feeling of insecurity of favela residents.

L'exercice de l'autorité par les groupes criminels

Authority as Exercised by Criminal Groups

Les factions émergent à partir des années 1960 et s’imposent dans les favelas. De nos jours, selon Michel Misse, 10 à 15 % de la population de la ville vit dans des zones contrôlées par les trafiquants (Misse, 2011, p. 18), toute une partie des favelas et périphéries étant, par ailleurs, dominée par des milices. La concurrence entre les factions ennemies a entraîné une prolifération d’actes de violence, une «course à l’armement» ainsi qu’un rapprochement entre criminels, policiers et autres pouvoirs publics corrompus. Par ailleurs, les trafiquants contrôlent d’autres services économiques informels (internet, immobilier, transports,…) multipliant pouvoirs et influences autoritaires sur le territoire (Zaluar, 1998) (Machado da Silva, 2008). L’autorité imposée sur l’espace par les trafiquants prend différentes formes, en fonction d’une part du statut du chef – s’il est natif ou non de la favela –, mais également de son rapport avec les habitants, qui peut varier de la philanthropie au despotisme (Zaluar, 2004). En effet, certains tentent de légitimer leur pouvoir en participant à des actions «caritatives», telles que l’amélioration des équipements, l’aide aux plus démunis ou bien par l’offre de loisirs (bals de samba, funk,…) (Goirand, 2000). Certains parlent de « banditisme social » et attribuent une morale particulière aux trafiquants : celle de l’honneur, devenant alors souvent pour les adolescents le référentiel d’une identité locale (Valladares, 2006, p. 173). Il serait toutefois inapproprié de parler de connivence, même si le partage d’un même territoire induit des rapprochements de divers ordres (relations de voisinage, de parenté, liens économiques) : il s’agit plutôt d’une complicité contrainte et non désirée, soumise à la loi du trafic et du silence (Machado da Silva, 2008). Les trafiquants auraient ainsi tout intérêt à répondre à certains besoins de la population afin de garder le contrôle sur le territoire.

Factions began to emerge from the 1960s onwards, and spread in the favelas. Nowadays, according to Michel Misse, 10 to 15 % of the city’s population live in areas controlled by traffickers (Misse, 2011, p. 18), with entire sections of the favelas and peripheral areas being actually dominated by militias. Competition between enemy factions has led to the proliferation of violent acts, an arms race as well as the fact that criminals, police officers and other corrupt public authorities have drawn closer to one another. Furthermore, traffickers control other informal economic services (such as Internet, real estate and transport among others), multiplying authoritarian powers and influences over the territory (Zaluar, 1998) (Machado da Silva, 2008). The authority imposed upon the area by the traffickers, takes on different forms and depends on the status of their leader, i.e. whether or not he is a native of the favela, as well as his relationship with the residents, which can vary from philanthropy to despotism (Zaluar, 2004). Indeed, some try to legitimate their power by taking part in charity works, such as improving equipment, helping the most destitute or organising leisure activities such as dance events (Goirand, 2000). Some speak of “social crime” and describe traffickers’ morality as being underlain by honour, which then often becomes a local identity reference for adolescents (Valladares, 2006, p. 173). Nonetheless, it would be inappropriate to speak of complicity, even if sharing the same territory results in various kinds of rapprochements (relationships based on neighbourhood, kinship or economic links): it is more about an undesired complicity developed under duress, subjected to the law of trafficking and silence (Machado da Silva, 2008). As such, it is entirely in the interest of traffickers to meet the needs of the population to maintain control over the territory.

«Les trafiquants ne se préoccupaient pas des projets sociaux, évidemment, ils jouaient le rôle de la police parce qu’elle n’était pas présente ! […] C’était vraiment des actions ponctuelles. Ils n’ont jamais eu de projets, les seuls projets ici, c’est le gouvernement, les ONG ou les églises» (A., ancien président de l’association de résidents et habitant Rocinha).

“Traffickers did not worry about social projects; obviously, they were playing the role of the police force because there weren’t any! […] In reality, these were limited interventions. They’ve never had any plans; the only plans in this case were those of the government, NGOs or churches” (A., former chairman of the residents’ association of Rocinha).

Les trafiquants instaurent un ordre social violent, que Machado Da Silva (2008) nomme «sociabilité violente», Zaluar préfère parler d’éthos guerrier : «les pratiques du monde du crime sont liées à un éthos de masculinité exacerbé, exagéré, centré sur l’idée d’un chef despotique dont les ordres ne pourraient être désobéis» ou de «capital social négatif» qui serait un capital destructeur de civilité pesant sur l’organisation sociale de la favela et détruisant de façon violente les réseaux horizontaux locaux (Ribeiro & Zaluar, 2009, p. 575). Les relations sociales sont ainsi structurées par l’usage d’une force privatisée qui nourrit la violence urbaine. Inévitablement, cet ordre violent fragilise les relations et le lien social entre les habitants en générant la peur de la dénonciation et des représailles, et donc une perte de confiance envers le voisinage, ce qui rend difficile la constitution d’une base pour l’action collective. Selon Leeds, la violence physique et criminelle qui découle du trafic de drogue cache une violence structurelle institutionnelle plus occulte où des relations politiques néo-clientélistes avec ces communautés pauvres perdurent (Leeds, 1998). L’espace autoritaire se construit à travers différents processus de quadrillage territorial où les frontières des favelas sont tantôt imaginaires tantôt matérielles.

Traffickers establish a violent social order which Machado Da Silva (2008) calls “violent sociability”, although Zaluar prefers to speak of warrior ethos: “practices in the criminal world are linked to an ethos based on exacerbated and exaggerated masculinity, centred on the idea of a despotic leader whose orders could not be disobeyed”, or based on a “negative social capital” that would be a civility-destructing capital weighing on the social organisation of the favela, and violently destroying local horizontal networks (Ribeiro & Zaluar, 2009, p. 575). As such, social relations are structured through the use of a privatised force fuelling urban violence. Inevitably, this violent order makes relationships and the social link between residents vulnerable, by generating a fear of denunciation and retaliation, and therefore a loss of trust towards the neighbourhood, which makes the creation of a basis for collective action difficult. According to Leeds, physical and criminal violence ensuing from drug trafficking hides a more occult institutional structural violence, where the neo-clientelist political relations with these poor communities endure (Leeds, 1998). Authoritarian space is built through different processes of territorial control where the boundaries of favelas are sometimes real, sometimes material.

Des espaces autoritaires en transition démocratique? L’action publique en faveur de la justice socio-spatiale

Authoritarian Spaces in Democratic Transition: Public Intervention in Favour of Socio-Spatial Justice

Castel souligne que dans la société moderne, la sécurité, comme réponse à l'incertitude qui caractérise la vulnérabilité sociale, est une fonction régalienne de l'Etat-Providence (Castel, 2011). Or, les habitants des favelas sont dépossédés d’une partie de leurs droits fondamentaux, et notamment le droit à la sécurité au sens large du terme (physique, économique, sociale). Longtemps présent de façon incomplète et inefficace, l’État tente aujourd’hui d’infléchir les politiques publiques dans le sens d’une sécurisation des favelas, en combinant la «policiarisation» à d’autres actions publiques garantissant les droits fondamentaux et renforçant la participation de la société civile au débat public ainsi qu’à la prise de décision. C’est dans ce sens que l’on peut parler d’une transition démocratique dans les favelas. On passe de politiques de sécurité publique à des politiques publiques de sécurité. Les programmes s’ancrent dans une approche locale en cherchant à prendre en compte la singularité socio-spatiale des lieux qu’ils ciblent. Ces nouvelles orientations interviennent dans un contexte où la ville de Rio de Janeiro est portée sur le devant de la scène par l’accueil des évènements internationaux : sécuriser la ville devient une priorité.

Castel highlights the fact that, in modern society, security as a response to uncertainty characterising social vulnerability, is a kingly function of the Welfare State (Castel, 2011). Yet, the residents of favelas are dispossessed from part of their fundamental rights, particularly the right to security in the wide sense of the term (i.e. physical, economic and social security). Where, for a long time, the presence of the State was neither complete nor efficient, today the State tries to reorientate public policies towards making favelas secure, by combining “policiarisation” with other public interventions, thereby guarantying fundamental rights and reinforcing the participation of the civil society in public debates as well as decision making. It is in this sense that we can talk about democratic transition in favelas. There has been a shift from policies for public security to public policies for security. Programmes are taking root in a local approach by seeking to take into account the socio-spatial singularity of the targeted places. These new orientations intervene in a context where the city of Rio de Janeiro is brought to the front of the stage for hosting international events: making the city secure has become a priority.

Sécuriser les favelas pour mieux les intégrer à la ville

Securing Favelas with a View to Integrating Them Better into the City

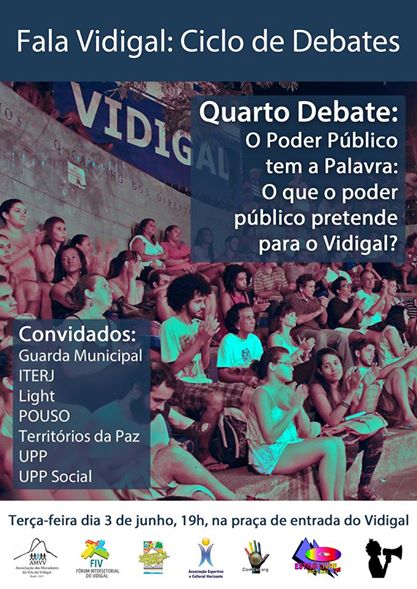

En 2008, le Secrétariat de Sécurité Publique de l’État de Rio de Janeiro élabore la politique dite de «pacification», visant à reprendre le contrôle des territoires dominés par des groupes criminels et à améliorer les rapports entre la population et les policiers en mettant en place une occupation permanente par des Unités de Police de Pacification (UPP). Ces opérations mobilisent de jeunes policiers récemment engagés, afin d’éviter les anciennes pratiques de corruption, ils reçoivent une prime mensuelle ainsi qu’une formation spécifique sur les principes de la police communautaire.

In 2008, the Public Security Secretariat of the State of Rio de Janeiro developed the so-called “pacification” policy, aiming at regaining control of the territories dominated by criminal groups, and at improving relations between the population and the police force, with the establishment of permanent Police Pacification Units (UPP). These operations mobilised newly recruited and young police officers in order to prevent former corruption practices. These young officers receive a monthly allowance as well as specific training on the principles of community policing.

Illustration 1: postes d'UPP à Vidigal et à Rocinha, Justine Ninnin, 2014

Illustration 1: UPP Posts in Vidigal and Rocinha, Justine Ninnin, 2014

Dans le champ de la sécurité publique, la pacification va dans le sens d’un rétablissement de certains droits fondamentaux qui étaient auparavant limités dans les favelas: le droit à la vie, le droit d’aller et venir, le droit de propriété, l’accès à la justice, à la santé, aux équipements et services collectifs (Zaluar, 2013). Entre 2012 et 2013, l’Institut de Sécurité Publique note une diminution de 26,5 % des homicides dans les zones ayant des UPP, alors que dans le reste de la ville ils augmentent de 9,7 %. On peut toutefois souligner le paradoxe de la pacification, qui d’une part se présente comme un moyen d’apporter la paix, et qui d’autre part s’entoure d’une matrice visuelle et discursive de guerre, particulièrement lors des interventions de reprise de contrôle des favelas : usage de tanks, d’hélicoptères, bataillons armés, cérémonies de hissage de drapeau et même appel en renfort des troupes de l’armée dans certains cas, le tout intitulé «choc de l’ordre».

In the field of public security, pacification works towards restoring certain fundamental rights that were previously limited in the favelas: the right to life, the right to freedom of movement, the right to property, access to justice, health, equipment and community services (Zaluar, 2013). Between 2012 and 2013, the Public Security Institute noted a decrease in homicides of 26,5 % in areas with UPPs, but an increase of 9,7 % in the rest of the city. We can nonetheless highlight the paradox of pacification which, on the one hand comes up as a means of providing peace, and on the other reflects a visual and discursive matrix of war, particularly during interventions for regaining control of favelas: use of tanks, helicopters and armed battalions, flag raising ceremonies and even in some cases army troops being called in as reinforcements, all this being part of the operation called “Shock of Order”.

Illustration 2: avril 2014, l’armée venue en renfort lors de la pacification du complexe de favelas de Marê, situé dans la zone nord de Rio de Janeiro.

Illustration 2: April 2014, the army came in as reinforcement during the pacification of the favela complex of Marê, situated in the north of Rio de Janeiro.

La présence quotidienne de policiers armés dans les rues des favelas pacifiées contraint les habitants à s’adapter à de nouvelles règles et pratiques sociales qui peuvent susciter au départ une certaine résistance; ce qui avant était résolu par les groupes criminels l’est aujourd’hui par la police. L’élargissement des fonctions dévolues à la police désoriente une partie de la population quant au comportement à adopter face à des policiers à la fois détenteurs de la violence légitime, médiateurs et parfois même éducateurs. Il y aurait un transfert de responsabilités de gouvernance aux UPPs. Si pour certains habitants l’introduction de policiers armés dans l’espace public, de jour comme de nuit, est garant d’une plus grande sécurité, pour d’autres elle est perçue comme une intrusion «militaire» dans leur quotidien. Elle contribue à pérenniser la «militarisation idéologique de la sécurité publique» dans l’espace urbain, c'est-à-dire «la transposition, au domaine de la sécurité publique, des conceptions, valeurs et croyances de la doctrine militaire, entraînant au sein de la société la cristallisation d’une conception centrée sur l’idée de guerre» (Silva, 1996, p. 501). C’est ainsi que Graham (2012) observait une militarisation de l’espace urbain à Rio de Janeiro avec l’exportation de pratique ouvertement militaire, le terrain urbain étant alors perçu par les forces militaires comme des zones de conflit nécessitant une surveillance permanente. Par exemple, dans les zones d’UPPs, des caméras de surveillance ont été installées. Selon Deluchey, «accompagnée de son environnement idéologique, l’expression «guerre contre la criminalité» pourrait véhiculer une représentation autoritaire de la société brésilienne et de son ordre social et politique» (Deluchey, 2003, p. 174). Les règles imposées par l’UPP sont parfois considérées comme injustes et autoritaires: interdiction des bals funk, demande d’autorisation pour réaliser des évènements sur les espaces publics (voire privés), contrôles et fouilles à répétition sans mandat, et également des cas d’agression, de torture, d’homicide ou de disparition liés aux UPP[2]3. Une police qui changerait de nom, mais pas de comportement. Le débat ne porte pas seulement sur la démilitarisation de la police au profit d’une réelle police communautaire, mais sur une réforme globale du système judiciaire du Brésil, où, tacitement, deux états de droit cohabitent: la favela et le reste, et où par conséquent deux types d’actions policières existent.

The daily presence of armed police officers in the streets of pacified favelas, forces residents to adapt to new social rules and practices that, at the beginning, can provoke a certain resistance; what was previously resolved by criminal groups is resolved today by the police. The fact that police duties are being extended is disorienting for part of the population which is not sure what behaviour to adopt, in the face of police officers who are the holders of legitimate violence, mediators and sometimes educators even. There seems to be a transfer of governance responsibilities to UPPs. While for certain residents, the introduction of armed police officers in the public space, by day or night, ensures greater security, for others it is perceived as “military” intrusion in their daily life. It contributes to perpetuating the “ideological militarisation of public security” in urban space, i.e. “the transposition, in the public security domain, of the conceptions, values and beliefs of military doctrine, bringing about, within society, the crystallisation of a conception centred on the idea of war” (Silva, 1996, p. 501). As such, Graham (2012) observed a militarisation of the urban space in Rio de Janeiro, with the export of openly military practices, the urban field then being perceived by militaries as conflict areas requiring permanent surveillance. For example, in UPP areas, surveillance cameras have been installed. According to Deluchey, “the expression ‘war against crime’, accompanied by its ideological environment, could convey an authoritarian representation of Brazilian society and its social and political order” (Deluchey, 2003, p. 174). The rules imposed by UPPs are sometimes considered as unfair and authoritarian: prohibition of balls, requests for authorisation to organise events in public (or even private) areas, repeated checks and searches without a mandate as well as cases of assault, torture, homicide or disappearance linked to the UPPs[2]3… in other words a police force that changed its name but not its behaviour. The debate concerns not only the demilitarisation of the police to the benefit of a real community police, but also a global reform of the judicial system in Brazil where, tacitly, two rules of law cohabitate: favelas and the rest, and where, consequently, two types of police interventions exist.

La période de fin 2013 et début 2014 a été marquée par une recrudescence, dans les favelas pacifiées, des confrontations entre trafiquants et policiers, de la répression violente de mobilisations collectives d’habitants ou encore d’attaques envers les UPPs. La crise actuelle semble provenir d’une accumulation de tensions, d’un malaise social et spatial dont les grandes manifestations de juin 2013 ont notamment été le reflet. Les trafiquants profiteraient alors de ces tensions pour réaffirmer leur pouvoir sur ces territoires. Le trafic n’avait pourtant pas disparu. La pacification a entrainé une redéfinition des rapports entre policiers et trafiquants qui partagent à présent un même territoire quotidiennement. Les stratégies des trafiquants changent, ils sont plus mobiles, moins visiblement armés et les points de vente sont plus discrets et s’accordent parfois tacitement avec les policiers pour conserver le statu quo.

The period between the end of 2013 and the beginning of 2014 was marked by a new outbreak of confrontations in pacified favelas, between traffickers and police officers, of violent episodes of repression of collective resident mobilisations or, still, of attacks towards UPPs. The current crisis seems to come from an accumulation of tension, from a feeling of social and spatial discomfort that was initially translated into large demonstrations in June 2013. Traffickers were to benefit from these tensions to reassert their power over these territories, although trafficking had in no way disappeared. Pacification brought about a redefinition of the relations between police officers and traffickers, both ending up having to share the same territory daily. Traffickers adopt different strategies; they are more mobile, less visibly armed and their points of sales are more discreet; and sometimes traffickers tacitly agree with police officers in order to maintain the status quo.

«Le pauvre n’est jamais sorti de la répression. Quand la dictature s’est arrêtée, c’était au tour du trafic de s’installer, puis aujourd’hui il y a les UPP, qui sont également une autre forme de répression. Sauf que maintenant, on vit dans la favela avec deux formes de répression, d’une part le trafic continue et d’autre part, la police. Si on regarde la télévision, on n’arrête pas d’entendre parler de confrontations, d’échange de tirs, de morts d’innocents. Il y a donc deux formes de répression au sein d’un même territoire, ce sont en quelque sorte des formes de dictature» (F., leader communautaire et habitant de Rocinha).

“Poor people have never been out of the repression. When the dictatorship stopped, trafficking was up next, followed today by UPPs that are also another form of repression. Except that now, one lives in favelas with two forms of repression: trafficking on the one hand and the police on the other. When watching television, all one hears about are the confrontations, the gun shots and the deaths of innocent people. There are two forms of repression within the same territory; in some way they are forms of dictatorship” (F., Rocinha community leader and resident).

La politique de pacification ne peut à elle seule garantir l’accès à la sécurité des habitants et leur émancipation de ces espaces autoritaires : l’inclusion des favelas passe également par le renforcement d’autres registres des politiques publiques.

The pacification policy cannot guarantee on its own that residents will have access to security and be emancipated from these authoritarian spaces: the inclusion of favelas also goes through the reinforcement of other public policy registers.

Vers un espace plus juste: mobilisation des outils de la «bonne gouvernance» et «effet UPP»

Towards a Fairer Space: Mobilising the Tools of Good Governance and UPP Effect

Avant la pacification, différents programmes publics étaient déjà à l’œuvre dans les favelas. C’est notamment le cas du programme Favela-Bairro et du Programme d’Accélération de la Croissance (PAC) qui, à Rocinha par exemple, a apporté de nombreuses améliorations: construction d’une Unité de Premiers Secours (UPA), d’une bibliothèque, d’un complexe sportif, de logements sociaux et élargissement de rues. La pacification devrait jouer le rôle de «facilitateur de l’exécution des travaux d’infrastructure et d’action sociale» (Batista Carvalho, 2013, p. 295). Le programme «Rio Mais Social» de la municipalité en partenariat avec ONU-Habitat met relation, dans les favelas pacifiées, les services économiques, sociaux ou culturels (publics et privés), fait remonter les demandes locales et cherche à valoriser la participation de la société civile. Toutefois, la multiplication des programmes publics tend à superposer les actions sans les articuler. La population des favelas souligne notamment l’insuffisance d’information, l’inachèvement de certains projets et le manque de priorité en favorisant des projets visibles au détriment de l’indispensable à Rocinha par exemple, les habitants se mobilisent contre le projet de téléphérique du PAC 2 au nom de la priorité à accorder aux travaux d’assainissement de base. En effet, dans cette favela, qui est encore un foyer de tuberculose, de nombreux égouts sont à ciel ouvert, les ordures s’entassent dans les ruelles et des quartiers entiers sont souvent privés d’eau et d’électricité.La société civile se trouve finalement peu présente dans les prises de décision. Le modèle bottom up de «bonne gouvernance» c'est-à-dire des modes d’échanges et d’agrégation entre acteurs individuels et collectifs, peine à devenir efficient.

Before pacification, various public programmes were already at work in the favelas. This is the case of the Favela-Bairro programme in particular, as well as the Growth Acceleration Programme (PAC) that, in Rocinha for example, brought about many improvements: the construction of a First Aid Unit (UPA), a library, a sports complex, housing projects and the widening of the streets. Pacification should be playing the role of “facilitator of the execution of infrastructure works and social action” (Batista Carvalho, 2013, p. 295). In pacified favelas, the Rio Mais Social programme of the municipality, in partnership with UN-Habitat, puts (public and private) economic, social or cultural services in contact, escalates local requests and seeks to develop the participation of the civil society. However, the multiplication of public programmes tends to superimpose interventions without linking them. Favela residents highlight in particular the fact that information is insufficient, some projects are not completed and there is a lack of priority insofar as visible projects are favoured to the detriment of the absolute necessary, as in Rocinha for example, where residents are mobilising against the PAC 2 Cableway Project when priority should have been given to basic sanitation works. Indeed, in this favela where one still finds tuberculosis, many drains are open, refuse pile up in the streets and entire suburbs are often deprived of water and electricity. In the end, the civil society is not very present in decision making. The bottom-up model of “good governance”, i.e. of the exchange and aggregation modes between individual and collective actors, struggles to become efficient.

Le processus d'inclusion des favelas dans la ville engendre des effets paradoxaux : plus les espaces évoluent vers des formes possédant les attributs de l’urbanité, plus ils se valorisent et plus les populations vulnérables ont du mal à s’y maintenir. « L’effet UPP » a notamment contribué à accentuer la spéculation immobilière et le processus de conquête par la classe moyenne des favelas de la zone sud de Rio de Janeiro, comme c’est le cas notamment à Vidigal, obligeant une partie des habitants les plus pauvres à quitter le quartier où ils vivaient pour s’installer plus loin en périphérie. Ceci ressemble au phénomène que Neil Smith nomme « rent gap », par lequel la perspective de plus-value sur des terrains à réhabiliter pousse les classes aisées à investir, ceci générant alors un processus de « gentrification » (Smith, 1996). Le prix du sol augmente et le profil sociologique du quartier concerné change. Certains habitants prennent part à cette nouvelle économie de marché (location et vente de biens immobiliers, ouverture de commerces,…), tandis que d’autres n'arrivent pas à suivre l'augmentation du coût de la vie, notamment des loyers, ou à s’acquitter des nouvelles factures liées à la régularisation de l’espace (électricité, eau, impôt sur la propriété du sol, etc.). Le marché devient en quelque sorte un nouveau pouvoir autoritaire dans les favelas.

The process to include favelas into the city generates paradoxical effects: the more areas evolve towards forms with urbanity attributes, the more value they take on and the more vulnerable populations find it hard to stay there. The “UPP effect” contributes in particular to emphasising real estate speculation, and the process whereby the middle class is buying up favelas in the south of Rio de Janeiro, as is the case in Vidigal in particular, forcing part of the poorest residents to leave the suburb and settle further away, on the outskirt. This is similar to the phenomenon Neil Smith calls ‘rent gap’, through which the prospect of capital gain on lands to be rehabilitated brings the well-off classes to invest there, leading to gentrification (Smith, 1996). The land price increases and the sociological profile of the suburb in question changes. Some residents take part in this new market economy (renting and selling real estate and opening shops among other things), while others fall behind, particularly concerning the payment of rents or newly acquired bills linked to the regularisation of space (electricity, water, property taxes, etc.), because of the increase in the cost of life. As a result, the market somehow becomes a new authoritarian power in the favelas.

Se mobiliser dans un ordre autoritaire: sphère intermédiaire et répertoire d’actions possibles

Joining Forces in an Authoritarian Order: Intermediary Spheres and Possible Interventions

Dans ces territoires où se sont relayés différents systèmes de répression, l’espace public a été affecté par un ordre socio-spatial autoritaire et la société civile locale a dû s’adapter. Elle puise notamment ses ressources sociales et symboliques dans la sphère intermédiaire[3], c’est-à-dire des lieux de médiations, de chevauchements entre le public et le privé-domestique, où les formes de socialisations propres peuvent faire émerger des initiatives collectives.Il peut s’agir tout autant de réseaux religieux ou de voisinage, ainsi que d’ONGs ou d’associations de résidents.

In these territories which have witnessed various consecutive repressive systems, public space has been affected by an authoritarian socio-spatial order, which means that the local civil society had to adapt, drawing its social and symbolic resources on the intermediary sphere[3], i.e. places of mediation and overlapping between the public and private domains, where forms of actual socialisation can bring out collective initiatives. These can be religious or neighbourhood networks, as well as NGOs or residents’ associations.

Les réseaux comme ressource sociale et symbolique

Networks as Social and Symbolic Resource

Le terme de communauté, pour parler des favelas, permet de valoriser un quotidien marqué par des liens de solidarité et d’entre-aide, différents de ce qui existe dans le reste de la ville, considéré comme plus individualiste. Ces représentations, si elles ont une part de réalité, sont souvent mobilisées afin de réagir contre les stigmatisations. Fondés sur des dimensions spatiales, symboliques et sociales, les liens entre habitants s’organisent en réseaux: familiaux, de voisinage ou encore religieux, construits sur des relations de dépendance à travers une logique de don / contre-don (Ribeiro & Zaluar, 2009). Selon Leite «les habitants font l’usage des répertoires possibles, ainsi, ils développent différentes formes d’action recherchant l’abri et l’appui dans les familles, les amis, les groupes religieux, pour construire une esquisse de ce que Giddens désigne «sécurité ontologique» et affronter la violence et l’insécurité présentes quotidiennement sur leur lieu d’habitation » (Leite, 2008, p. 135). En s’intéressant aux organisations de voisinage (églises, écoles, clubs de foot, écoles de samba, etc.) comme productrices d’ordre et de contrôle social, Ribeiro et Zaluar (2009) s’interrogent sur l’efficacité collective, c’est-à-dire la capacité des habitants et du voisinage à réaliser leurs valeurs communes et à maintenir un contrôle social effectif sur les personnes. Les femmes par exemple, et plus particulièrement les mères, jouent un rôle primordial dans l’efficacité collective, au travers d’un pouvoir intrinsèquement légitime de contrôle et de mobilisation.

The community, as far as favelas are concerned, makes it possible to enhance the value of everyday life through relationships based on solidarity and mutual aid, unlike what exists in the rest of the city, which is considered to be more individualistic. These representations are often mobilised as a reaction against condemnations. Founded on spatial, symbolic and social dimensions, relationships between residents are organised into family, neighbourhood or religious networks, built on relations of dependency through a process of donations/counter-donations (Ribeiro & Zaluar, 2009). According to Leite, “residents make use of possible situations; as such, they develop different forms of interventions seeking shelter and support within families, among friends, in religious groups, so as to get an idea of what Giddens refers to as “ontological security” and brave the violence and insecurity found daily in their place of residence (Leite, 2008, p. 135). By taking an interest in neighbourhood organisations (churches, schools, soccer clubs, samba schools, etc.) as social order and control-producing organisations, Ribeiro and Zaluar (2009) question collective efficiency, i.e. the capacity of residents and neighbourhoods to realise shared values and maintain efficient social control. Women, for example, and mothers in particular, play a crucial role in collective efficiency, through an intrinsically legitimate power of control and mobilisation.

«Les religieux et les mères de famille ont plus de facilité à discuter avec les bandits, ils ont plus de pouvoir également dans l’action collective […]. À l’époque des mutirões [effort collectif d’habitants] pour nettoyer et agrandir les canaux des eaux usées, je me suis interrogé sur le fait que les femmes étaient systématiquement plus nombreuses que les hommes, mais c’est parce que ce sont elles, dans les tâches quotidiennes, qui subissent le plus les désagréments du manque d’assainissement» (M., leader communautaire et habitant de Rocinha).

“People belonging to a religious order as well as mothers talk more easily with gangsters, they also have more authority in a collective intervention […]. At the time of the mutirões or residents’ collective efforts to clean up and widen waste water canals, I was wondering why women were systematically in greater numbers than men, but that’s because they are the ones who, in the daily chores, are subjected the most to the inconvenience of the lack of sanitation” (M., Rocinha community leader and resident).

Ces réseaux ne sont, toutefois, pas hermétiques aux forces autoritaires, et les liens sociaux en sont fragilisés. En effet, la construction d’une véritable culture civique de participation dans la résolution des problèmes locaux est très affaiblie par la présence d’armes, de violence et de répression (étatique, para-étatique ou criminelle) (Machado da Silva, 2008).

However, these networks are not impervious to authoritarian forces, weakening social relations in the process. Indeed, the construction a real civic culture of participation, in the resolution of local problems, is very weakened by the presence of (State, parastatal or criminal) weapons, violence and repression (Machado da Silva, 2008).

Les mouvements communautaires et les associations de résidents

Community Movements and Residents’ Associations

L’idéologie communautaire a fortement été influencée par l’Église catholique: la Théologie de la Libération, dans les années 1960, a apporté un nouveau regard sur les pauvres, qui ne sont plus envisagés dans une perspective caritative d’assistance, mais s’affirment comme des sujets sociaux autonomes et porteurs de droits. L’Église dénonce les injustices engendrées par les mécanismes d’oppression et l’action collective commence à s’organiser au sein des Communautés Ecclésiales de Base (CEB). Sous la dictature, les CEB sont presque les lieux uniques où les regroupements populaires étaient autorisés, pourtant, ils se sont constitués en structures d’opposition au régime militaire (Goirand, 2010) (Lesbaupin, 1997). Ainsi, en période de répression, pendant la dictature, des mouvements populaires se sont organisés autour des questions de conditions de vie, de revendications de services publics et de droits sociaux.

Community ideology has been highly influenced by the Catholic Church: Liberation Theology, in the 1960s, brought a new outlook on the poor who were no longer perceived as being in need of charity, but who asserted themselves as autonomous social subjects with rights. The Church denounced cases of injustice generated by oppression mechanisms, and collective intervention was beginning to organise itself within Basic Christian Communities (BCC). Under the dictatorship, BCCs were unique places where people were authorised to group together. In the end, they became structures of opposition to the military regime (Goirand, 2010) (Lesbaupin, 1997). Also, during the repression period of the dictatorship, popular movements were organised around issues of living conditions as well as public service and social rights claims.

«À cette période, le mouvement communautaire était pourtant très fort, il arrivait à s’organiser malgré la situation, ce mouvement n’a pas pris les armes, il n’a pas été vers une confrontation directe mais il a souffert de répressions incalculables […] Ça n’a pas été facile. Qui allait protester dans la rue, à l’époque de la dictature, était molesté ou ignoré. C’est à cette période pourtant, selon moi, que Rocinha a été la plus productive» (F., leader communautaire et habitant de Rocinha).

“Yet, at the time, the community movement was very strong; it managed to organise itself despite the situation. This movement did not rise up in arms; it did not move towards direct confrontation, although it did suffer from uncountable cases of repression […] It was not easy. Whoever was going to protest in the street, at the time of the dictatorship, was manhandled or ignored. Yet it is during that period, according to me, that Rocinha was the most productive” (F., Rocinha community leader and resident).

Ces mouvements communautaires reposent sur une multiplicité d’organisations locales et s’articulent notamment avec les associations de résidents, créées dans les années 1960, qui relaient les demandes des habitants. Si au départ, elles défendent leur autonomie face au gouvernement, avec le processus de démocratisation de la fin des années 1970, les partis politiques, principalement de gauche, commencent à se disputer le contrôle de ces associations. La perte d’autonomie est alors dénoncée par les habitants, tout comme les pratiques de cooptation. En conséquence, ces associations se focalisent de plus en plus sur la gestion des ressources et les services publics, plus que sur la défense des intérêts des habitants. Par ailleurs, à partir des années 1980, les trafiquants commencent également à s’intéresser à ces élections. Le poids de ces organisations dans les revendications locales s’affaiblit, en raison d’une part de la pression exercée par les trafiquants et d’autre part de la perte d’autonomie politique (Zaluar, 1998) (Soares Gonçalves, 2007) (Goirand, 2010) (Goirand, 2000).

These community movements relied on the many local organisations, linking in particular with the residents’ associations created in the 1960s to relay their requests. While at first these associations defended their autonomy against the government, with the democratisation process of the end of the 1970s, political parties – left wing parties mainly – began to fight over the control of these associations. The loss of autonomy was then denounced by the residents, as were co-opting practices. Consequently, these associations were focusing increasingly on the management of resources and public services, more than on the defence of residents’ interests. Moreover, from the 1980s onwards, traffickers also began to take an interest in these elections. The weight of these organisations in local claims weakened, due on the one hand to the pressure exercised by traffickers, and on the other to the loss of political autonomy (Zaluar, 1998) (Soares Gonçalves, 2007) (Goirand, 2010) (Goirand, 2000).

«Les associations de résidents ont toujours eu un rôle très important, mais elles ont perdu de la force, en raison du pouvoir que le trafic a commencé à prendre dans les favelas, politiquement, socialement et économiquement» (F., leader communautaire et habitant).

“Residents’ associations have always played a very important role, but they lost power, due to the importance that trafficking began to take in the favelas, politically, socially and economically” (F., community leader and resident).

À cette même période, la Théologie de la Libération, critiquée et jugée trop politisée par le Vatican, perd également de son influence. Le repli de l’action catholique, l’instauration d’un ordre violent lié au trafic et la criminalisation des espaces de revendication «traditionnels» restreignent les mouvements populaires. L’action sociale se disperse et se modifie, notamment avec l’arrivée des ONG qui proposent un autre modèle d’action, sous forme de partenariat avec les pouvoirs publics et les organisations internationales pour l’implantation de projets sociaux.

During that same period, Liberation Theology that was criticised and deemed too politicised by the Vatican, also lost its influence. The withdrawal of catholic interventions, the establishment of a violent order linked to trafficking, and the criminalisation of the “traditional” spheres of protest restricted mass movements. Social intervention dissipated and became modified, particularly with the arrival of NGOs that offered another model of intervention, in the form of partnerships with the public authorities and international organisations for the establishment of social projects.

La montée en puissance des ONG

The Rise of NGOs

À partir des années 1990, les mouvements populaires se fragmentent en de multiples organisations et se cristallisent en institutions de plus en plus bureaucratisées. Les actions sociales se professionnalisent, il existe dorénavant une réelle nécessité de compétences, de savoirs et savoir-faire spécifiques. Cette logique de professionnalisation prend place dans un contexte de décentralisation des fonctions de l’État, voire de déresponsabilisation de l’ État (Dagnino & Tatagiba, 2010).

From the 1990s onwards, mass movements broke up into many organisations and crystallised into increasingly bureaucratised institutions. Social interventions turned professional; from then on there was a real need for specific skills, knowledge and know-how. This professionalisation process took place in a context of State decentralisation, even taking away responsibility from the State (Dagnino & Tatagiba, 2010).

«Ces organisations vont être de plus en plus utilisées par le gouvernement pour faire des politiques publiques. […] Le problème au Brésil est que le gouvernement finance principalement les projets qui sont en rapport avec le gouvernement et non en rapport avec la société en général. Il y a une relation utilitariste de l’État envers la société civile. […] Les ressources sont données aux organisations qui sont très proches de l’État. Ce qui n’est finalement pas exactement une décentralisation, l’État garde en effet un pouvoir central, il n’y a pas décentralisation du pouvoir de décision, seulement décentralisation de l’exécution des charges» (entretien avec Paulo Haus Martin, avocat spécialisé dans les ONG, 2011).

“These organisations are going to be used increasingly by the government to make public policies. […] The problem in Brazil is that the government mainly finances projects that are related to the government and not to society in general. There is a utilitarian relationship of the State towards civil society. […] Resources are given to organisations that are very close to the State. Which in the end is not decentralisation exactly, indeed the State keeps a central power, there is no decentralisation as far as decision power is concerned, there is only decentralisation as far as executing the responsibilities of the State are concerned” (interview with Paulo Haus Martin, lawyer specialised in NGOs, 2011).

Les habitants habitués à voir la sphère traditionnelle de revendication accaparée par des pouvoirs et des intérêts personnels se méfient tout autant des ONGs, souvent accusées de chercher à faire des bénéfices sur le dos des projets sociaux.

Residents who are used to seeing the traditional sphere of protest monopolised by authorities and personal interests, are just as careful about NGOs that are often accused of seeking to make a profit at the expense of the social projects.

«Les ONGs ont commencé à entrer dans les communautés avec des projets sociaux et souvent elles ne dialoguaient pas avec les habitants […] Il y a beaucoup de gens qui veulent créer des ONG pour leur propre bénéfice et parfois on ne sait pas bien d’où viennent les financements» (A., habitant de Vidigal).

“NGOs began to enter communities with social projects but often did not create a dialogue with the residents […] There are many people who want to create NGOs for their own benefit and sometimes we are not sure where funding comes from” (A., Vidigal resident).

La faiblesse des institutions démocratiques et la privatisation de la sphère publique entraineraient alors un déclin du sens communautaire et une dilution des relations sociales.

The weakness of the democratic institutions and the privatisation of the public sphere are likely to cause a decline in the sense of community and a dilution in social relations.

«Quand la communauté a arrêté de lutter pour les biens communs à tous, elle a arrêté d’être une communauté. Elle était en même temps communauté et favela, aujourd’hui elle est seulement favela. J’entends la communauté dans une perspective de ce qui est commun à tous : l’exercice de la citoyenneté pour la lutte pour notre espace» (F., leader communautaire et habitant de Rocinha).

“When the community stopped fighting for the rights of all residents, it stopped being a community. It was community and favela at the same time; today it is only favela. I understand community in the perspective of what is common to all: the exercise of citizenship with a view to fighting for our space” (F., Rocinha community leader and resident).

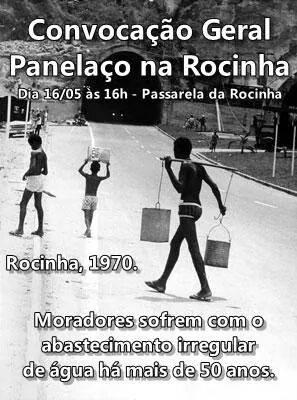

Finalement, nous pouvons souligner que dans un contexte de pression autoritaire sur les espaces traditionnels de revendication, de la part des trafiquants, des politiciens ou parfois d'élite et d’entrepreneurs locaux puissants, pour défendre des intérêts particuliers, les actions collectives se fragmentent, elles s’organisent au sein d’ONGs, de réseaux de voisinage, de paroisses et les différents projets ont du mal à s’articuler entre eux et avec les pouvoirs publics. L’autonomie est souvent présentée par les leaders communautaires non seulement comme une stratégie, mais aussi comme une valeur en soi. «À la recherche d’une voie alternative entre autoritarisme, populisme et révolution, beaucoup d’analystes ont vu dans les mouvements autonomes des sociétés civiles une source possible d’innovation sociale» (Goirand, 2010, p. 455). Si les cadres de l’organisation collective ont changé, certaines revendications restent les mêmes. Dans le cas de Rocinha, par exemple, que ce soit lors de la dictature, sous la domination des trafiquants ou une fois «pacifiée», qu’elle soit considérée comme favela, communauté ou quartier (Rocinha est une région administrative depuis 1986), les habitants réclament toujours des conditions d’habitat digne, qu’il s’agisse de l’assainissement de base ou tout simplement un accès permanent pour tous à l’eau courante.

Finally, we can point out that in a context where authoritarian pressure has been put on the traditional spheres of protest by traffickers, politicians or sometimes elites and powerful local contractors, in order to defend personal interests, collective interventions break up; they are organised within NGOs, neighbourhood or parish networks, and the different projects find it hard to link between them, and with the public authorities. Autonomy is often presented by community leaders not only as a strategy, but also as a value in itself. “In their search for another way between authoritarianism, populism and revolution, many analysts have seen a possible source of social innovation in the autonomous movements of civil societies” (Goirand, 2010, p. 455). While collective organisation frameworks have changed, certain claims remain the same. In the case of Rocinha for example, whether during the dictatorship, under the domination of traffickers or once it was pacified, and whether it is considered as a favela, a community or a suburb (Rocinha is an administrative region since 1986), its residents are still calling for dignified living conditions, regarding basic sanitation or simply permanent access to running water for all.

Illustration 3 : Tracte d’appel au rassemblement pour manifester à Rocinha