Le discours autochtone sur le territoire et la géographie

Indigenous Discourse on Territory and Geography

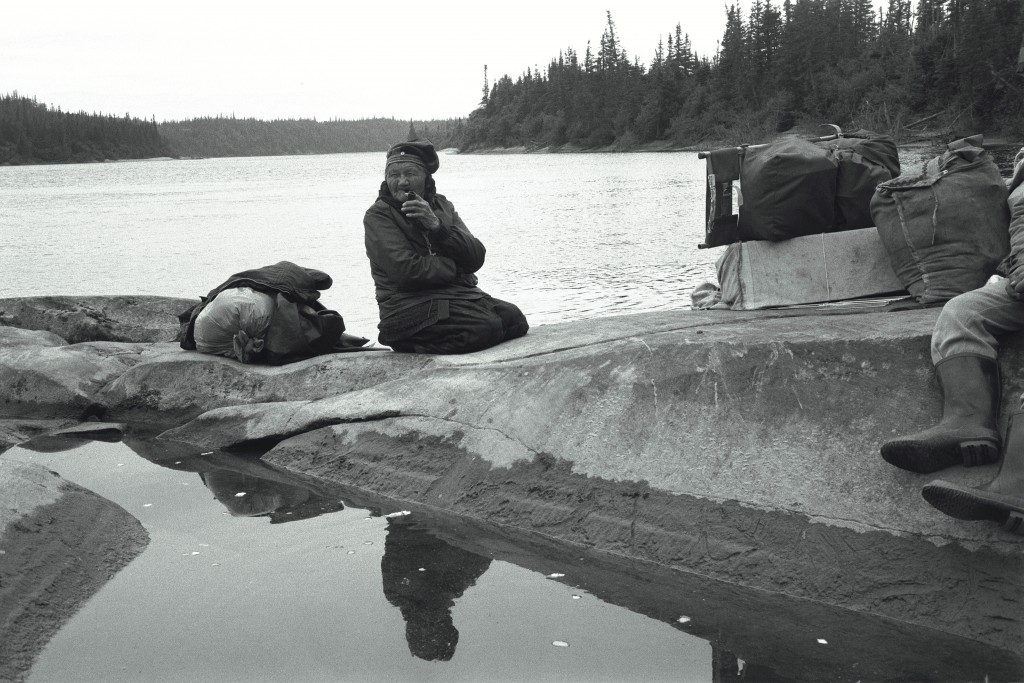

Lorsqu’en 1976 j’ai vu et entendu pour la première fois un vieil Amérindien parler de son territoire, de sa manière de nomadiser, des activités de chasseurs, trappeurs, pêcheurs et cueilleurs que lui et son peuple y pratiquaient, j’ai été frappée par la richesse de ses paroles, le sentiment d’affection qu’il éprouvait pour sa forêt et le caractère holistique de son discours. En effet, le vieil homme y intégrait également son dialogue avec les autres êtres vivants, la solidarité entre les familles étendues, la destruction de la forêt et du gibier, la résistance aux compagnies forestières et minières, les tracasseries bureaucratiques, et encore le rêve inspirateur d'actions décisives et la mythologie et l'histoire de son peuple. Il me semblait que le territoire constituait pour cet aîné un lieu d'intégration des éléments de sa pensée et de son expérience, tant au niveau individuel que collectif. Sa façon de réunir tous ces éléments incluait un mode spécifique de pratiquer l'espace et le temps car ce qui conduisait le cheminement de sa pensée était son parcours en forêt, parcours stimulant perception, réflexion et imaginaire. Ce caractère inclusif ou holistique du discours de Michel Grégoire, Innu de la Côte Nord du St-Laurent au Québec, filmé par Arthur Lamothe[1], fut pour moi une véritable révélation. Un mot à connotation spirituelle qu’a posteriori je comprends comme porteur de relations sacrées avec un territoire et ses habitants animaux, arbres, humains et esprits, ces mêmes relations qui existent pour de nombreux peuples autochtones du monde, comme j’ai eu l’occasion de l’entendre dire maintes fois par leurs représentant·e·s aux Nations Unies, par la suite.

When, in 1976, I saw and heard for the first time an Amerindian elderly talking about his territory, about the way he lived a nomadic life, about the activities of the hunter, the trapper, the fisherman and the gatherer as practiced by him and his people, I was struck by how rich his words were, by the affection he showed for his forest and by the holistic nature of his discourse. Indeed, the elderly man had also included in it his dialogue with the other living beings, the solidarity that existed between extended families, the destruction of the forest and the game, resistance against forestry and mining companies, red tape or, still, the inspiring dream of decisive actions, mythology and the history of his people. It seemed to me that, for this elderly man, the territory constituted a place where the elements of his thought and experience could be integrated, whether individually or collectively. His way of bringing together all these elements included a specific way of practising space and time, for what was driving his thoughts was his journey in the forest, a journey that stimulated his perception, thoughts and imagination. The inclusive or holistic nature of the discourse of Michel Grégoire, an Innu of the Northern Coast of St-Laurent in Quebec, as filmed by Arthur Lamothe[1], was for me a true revelation. These words have a spiritual dimension which, a posteriori, I understand as bearing sacred relations with a territory and its inhabitants, whether these are animals, trees, humans or spirits, the very relations that exist for many Indigenous peoples around the world, as I had the opportunity to hear it said many times thereafter by their representatives at the United Nations.

Ma deuxième réaction fut alors de me dire que nous, les géographes, avions là une chance inespérée de sortir notre discipline des ornières dans lesquelles je la sentais empêtrée. C’était le milieu des années 1970 et la géographie était bien désorientée dans sa volonté d’affirmer son statut de science via l’utilisation de méthodes quantitatives, plutôt que d’accepter son identité d’être cette fameuse tentative de synthèse, de détection des « relations hommes-territoires », comme on disait alors ; tentative jamais achevée, jamais atteinte mais pourtant combien utile à la compréhension des réalités concrètes – réelles ou occultées – qui caractérisent la dynamique territoriale et la rétro-action qu’elle opère sur la société qui l’a engendrée.

My second reaction was to tell myself that we, Geographers, had an unexpected opportunity to bring our discipline out of the woods where, I felt, it was entangled. It was the mid-1970s, and geography was fairly disoriented in wanting to assert its status of science by using quantitative methods, rather than accepting its overarching goal of synthesis to famously detect “human-territory relations” as we put it in those days; an attempt that is never achieved, never reached, and yet so useful to understanding the – real or hidden – concrete realities that characterise territorial dynamics and its retro-action on the societies generating it.

Image 1 : En remontant la rivière Nutashkuan (Photo et © Volkmar Ziegler, 1976)

Image 1: Going up the Nutashkuan River (Photo and © Volkmar Ziegler, 1976)

Dès lors, mon parcours a été marqué par la volonté de comprendre ce qu’on a appelé plus tard les territorialités autochtones, y compris au niveau des représentations ; ceci non pas avec mon bagage théorique mais, au contraire, en m’en délestant. J’avais en effet le sentiment qu’il limiterait mes horizons, notamment parce qu’il n’était pas supposé intégrer des sentiments ou des intuitions. Ainsi, en travaillant avec des Autochtones et en les écoutant, « tout simplement », en me plaçant dans la mesure du possible dans leur espace-temps, j’ai essayé de comprendre le pourquoi et le comment de leur manière de penser et d’agir et, peu à peu, de comprendre leurs référents culturels. Pour moi, tout l’intérêt du travail résidait en quelque sorte à m’aventurer vers d’autres manières de relier les idées, les pratiques, les représentions et de les exprimer. La géographie me semblait être particulièrement propice à une telle démarche, dans la mesure où elle s’intéressait au même domaine que ses interlocuteurs et interlocutrices autochtones. En effet nous, les géographes, nous n’étudions pas des personnes ou des sociétés mais bien un objet tiers pour lequel nous partageons un intérêt commun : le territoire. Bien entendu, je n’ai avancé que de quelques petits pas sur ce chemin.

As a result, my journey has been characterised by that fact that I wanted to understand what was later called Indigenous territorialities, including at the level of representations; not with my theoretical background but, on the contrary, by relieving myself of it. Indeed, I had the feeling that my background would restrict my horizons, especially because it was not supposed to include feelings or intuitions. Also, by working with Indigenous peoples and by “simply” listening to them, by putting myself in their time-space as far as possible, I tried to understand the why and how of their way of thinking and doing and, progressively, of understanding their cultural referents. For me, the whole point of my work was, somehow, to venture towards other ways of linking ideas, practices and representations, and to express them. To me, geography seemed particularly conducive to such a process, insofar as it took an interest in the same domain as one’s Indigenous interlocutors. Indeed, we, the geographers, do not study people or societies, but a third object for which we share a common interest: territory. Of course, I have only made a few steps on that path.

Il m’est toujours apparu important que chercheur·e·s et intervenant·e·s sur un terrain donné explicitent leurs parcours respectifs afin qu’on puisse réellement tenir compte de leur impact dans le processus de recherche. Cela devrait participer de ce que j’appelle un processus d’« objectivation », semblable à celui de l’historien qui analyse ses sources en fonction notamment de la condition et de l’évolution de leurs auteurs. C’est pour cette raison que j’ai accepté avec enthousiasme la proposition d’Irène Hirt et de Beatrice Collignon de décrire mon parcours.

It always seems important to me that researchers and contributors working on a given field explain their respective trajectories in detail, so as to take into account their impact in the research process. This should partake of what I call an “objectivisation” process, similar to that of the historian who analyses his sources according to the condition and evolution of their authors in particular. That is why I have accepted with great enthusiasm to describe my professional journey, as suggested by Irène Hirt and Béatrice Collignon.

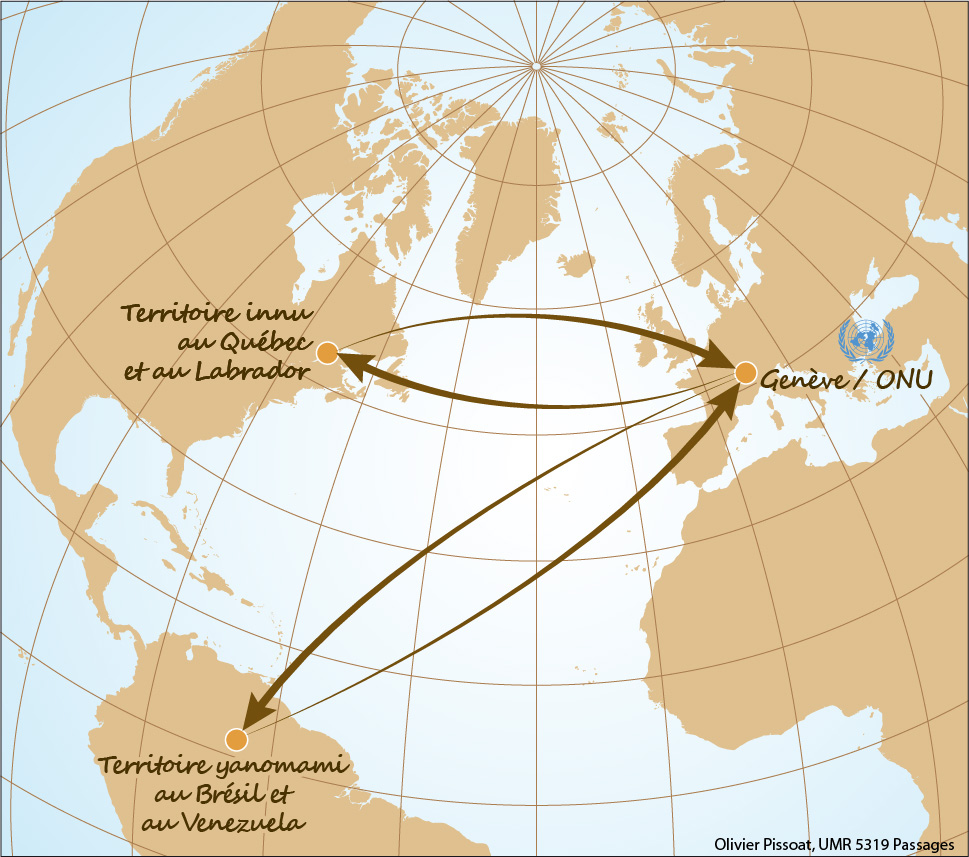

Carte 1 : Trajectoire de l’auteure

Map 1: Professional journey of the author

Lier théorie et pratique

Linking Theory and Practice

Lier théorie et pratique et être utile d’une manière ou d’une autre, telles étaient mes exigences personnelles de départ. Je considérais que faire des études universitaires était un privilège qui n’était pas donné à tout le monde – surtout pas aux femmes de ma génération – et, qu’en retour, je devais apporter quelque chose. Ainsi en 1971, une fois terminées mes deux licences d’histoire moderne et contemporaine, et de géographie, à l’Université de Genève, j’ai travaillé dans l’aménagement du territoire du Canton de Vaud, au sein d’une équipe multidisciplinaire d'architectes, géographes, pédologues, écologistes, agronomes, économistes et sociologues, tous masculins. Il s’agissait d’élaborer des plans de protection des sites et de les défendre face aux responsables communaux et, finalement, face au public lors des mises à l’enquête. Un travail passionnant, au cœur d’enjeux particulièrement importants - symboliquement et financièrement - dans un petit pays multilingue densément peuplé, où la spéculation foncière est forte et dont la beauté du paysage constitue l’un des ciments entre les cultures. Désireuse toutefois de découvrir d’autres horizons, j’ai décidé de reprendre des études de maîtrise, à la faculté de l’aménagement de l’Université de Montréal cette fois-ci.

Linking theory and practice and being useful in one way or another, these were my personal requirements from the beginning. I felt that studying at university was a privilege that was not given to everyone – especially not to the women of my generation – and that in return, I should be giving something back. In 1971, once I completed a BA in modern and contemporary history, and another in geography, both at the University of Geneva, I worked for the Town and Country Planning Department of the Canton of Vaud, with a multidisciplinary team of architects, geographers, pedologists, ecologists, agronomists, economists and sociologists, all of them male. The idea was to elaborate plans to protect sites and promote these plans with municipal or local authorities and ultimately the local people during the public inquiries. It was an exciting job, involving in particular – symbolically and financially – important issues in a small but densely populated multilingual country, where real-estate speculation is high and where the beauty of the landscape constitutes one of the cements between cultures. However, I wanted to discover other horizons and decided to study for a Master’s degree at the Faculty of Environmental Planning, but this time at the University of Montreal.

Le Québec, à cette époque, sortait de la Révolution tranquille qui l’avait introduit au monde contemporain. Il était caractérisé par la montée du nationalisme et de la défense de la langue française, défense qui me paraissait évidente en tant que francophone citoyenne d’un pays à majorité alémanique. Une effervescence particulière régnait, qui amenait à questionner idéologies et pratiques, de manière d’autant plus radicale que c’était aussi le temps de la contre-culture en Amérique du Nord, des expériences de vie communautaire et de la volonté de « retour aux sources » sur fond d’idéologie libertaire. Dans ce contexte, effectuer une maîtrise d’urbanisme, puis des recherches, et enseigner dans le domaine de l’aménagement du territoire et de la protection de la « nature », fut pour moi une expérience inoubliable ; d’autant que les équipes avec lesquelles je travaillais, à nouveau pluridisciplinaires, pratiquaient avant tout une démarche inductive, partant des problèmes, et axée sur les solutions.

Quebec, in those days, was just coming out of the Quiet Revolution that had led it to become part of the contemporary world. The Province was characterised by the rise of nationalism and the defence of the French language, a defence that seemed obvious to me, as a French-speaking citizen in a country where the majority was Alemannic. The place was bubbling with excitement; people began to challenge ideologies and practices, all the more radically since it was also the period of counter-culture in North America, that of community life experiences and the desire to “return to the source” with, in the background, libertarian ideology. In this context, doing a Master’s degree in Town Planning, then conducting research and teaching Town and Country Planning as well as “nature” conservation, was for me an unforgettable experience; especially since the multidisciplinary teams I worked with used an inductive approach, starting with problems and focusing on solutions.

Cultures et natures

Cultures and Natures

Différents mandats de recherche m’ont permis de prendre progressivement conscience de la réalité autochtone en Amérique du Nord et de son occultation. Ainsi, une étude attribuée par le Ministère des Terres et Forêts du Québec au Centre de Recherche et d’Innovation Urbaine de l’Université de Montréal nous a amené·e·s à interroger l’histoire de la conservation de la nature en Amérique du Nord. Le Ministère nous demandait comment mettre en œuvre une nouvelle loi sur les réserves écologiques promue par des milieux scientifiques en lien avec le Programme biologique international de l’UNESCO et qui prévoyait, notamment, leur interdiction à la population. Considérant que déjà de larges portions du territoire et de plusieurs rivières de la Belle-Province étaient concédées à des compagnies forestières, minières ou à des clubs privés de pêche, généralement anglo-canadiens ou américains, et donc à leur usage exclusif, cette nouvelle mesure était vue par bien des Québécois comme une nouvelle forme d’expropriation territoriale au nom d’une idéologie conservationniste étrangère à la région. Cette loi paraissait ainsi parachutée dans un contexte socio-culturel particulier, qui n’était pas pris en compte.

Different research mandates progressively led me to become aware of Indigenous realities in North America, and the fact that it was being eclipsed. A study attributed by the Ministère des Terres et Forêts (Department of Lands and Forests) of Quebec to the Urban Research and Innovation Centre of the University of Montreal, led us to question the history of nature conservation in North America. The Ministère asked us how they could implement a new law on ecological reserves, as promoted by the scientific world in relation with UNESCO’s International Biological Programme, a law that would prohibit the population from accessing these reserves. Seeing that large portions of the territory and several rivers of the Belle Province had been granted to forest or mining companies or, still, to private fishing clubs (all usually Anglo-Canadians or Americans), and therefore for their exclusive usage, this new measure was perceived by many Quebecois as a new form of territorial expropriation in the name of some foreign conservationist ideology. This law appeared to have landed in a specific socio-cultural context that had not been taken into account.

En examinant de façon critique l’histoire de la conservation de la nature en Amérique du Nord, il nous est apparu que l’idéologie qui la sous-tendait s’inscrivait dans la même logique d’opposition Homme-Nature que celle des destructeurs de la nature, une opposition qui avait pour résultat de réifier la nature et ainsi d’ouvrir la voie de sa destruction. Un tel constat, s’il est largement admis aujourd’hui, du moins en sciences sociales, était loin d’être évident à ce moment-là. Dans cette perspective conservationniste, les êtres humains, de maîtres de la nature, devenaient des prédateurs suprêmes, quels que soient leur culture et leur milieu d’origine, quelles que soient leurs responsabilités dans la destruction de l’environnement, en l’occurrence celui de la côte Est des États-Unis. Pour cette raison, il fallait créer des parcs nationaux dans les régions non dégradées par l’industrialisation, à l’Ouest des États-Unis. Le premier d’entre eux, le Parc de Yellowstone, nécessita la déportation forcée d’Indiens Shoshone dans la réserve de Wind River, un « exemple » parmi tant d’autres de dépossession territoriale à l’encontre de peuples autochtones, qui sera promu par la suite sur tous les continents. Ceci m’apparaissait particulièrement illogique et révoltant, puisque ces peuples n’avaient développé ni les techniques ni les valeurs nécessaires à la destruction de leur habitat. Ces politiques conservationnistes – promues par des représentant·e·s des classes fortunées – me semblaient émaner d’une épistémologie de laboratoire qui disséquait le savoir en parcelles artificielles. De ce fait, elles ne pouvaient guère être efficaces et, somme toute, n’étaient pas vraiment écologiques ! Dans cette logique, qui n’a pas disparu, les scientifiques s’octroyaient le rôle de sujets tout puissants face à une nature qu’ils transformaient en objet immuable alors que nous la considérions comme historique et culturelle. Aujourd’hui, l’Union Internationale pour la Conservation de la Nature et d’autres organisations conservationnistes commencent à admettre que la création d’aires protégées, dont font partie les parcs nationaux, n’a guère atteint ses objectifs de préservation.

By looking critically at the history of nature conservation in North America, it appeared that the ideology underlying it was part of the same Man-Nature logic as that of nature destroyers, an opposition that led to the reification of nature and opened the way for its destruction. While this might be widely admitted today in the Social Sciences at least, in those days it was far from obvious. In this conservationist perspective, human beings, the masters of nature, became the ultimate predators, irrespective of their culture and origin, and irrespective of their responsibilities in destroying the environment, more specifically that of the East Coast of the United States. It was for this reason that national parks needed to be created in regions that had not been damaged by industrialisation, as in the West of the United States. The first of these parks, the Yellowstone National Park, required the forced deportation of Shoshone Indians to the Wind River reserve, one “example” of territorial dispossession among many others against Indigenous peoples, which will be subsequently promoted on all continents. To me, this seemed particularly illogical and appalling, since these peoples had not developed the techniques or values needed to destroy their habitat. To me, these conservationist policies – promoted by the representatives of the wealthy classes – seemed to emanate from some laboratory epistemology dissecting knowledge into artificial bits. For this reason, they could not be very efficient and, when all is said and done, they were not truly ecological! In this approach, which is still current, scientists took on the role of all powerful subjects in the face of a nature they transformed into some unchanging object, while we considered nature as historical and cultural. Today, the International Union for Conservation of Nature as well as other conservationist organisations, have started to admit that the creation of protected areas, including national parks, has barely reached its conservation objectives.

Dans les mêmes années, un autre mandat de recherche relevant du programme « Homme et biosphère », également de l’UNESCO, consistait à étudier l’histoire de l’urbanisation du Québec, et devint vite une histoire de l’occupation territoriale de la Belle Province. Là, une surprise m’attendait : il était entendu pour mes collègues que cet historique devait remonter au 18ème siècle, c’est-à-dire à l’arrivée de Jacques Cartier, le premier explorateur européen du fleuve Saint-Laurent. En tant qu’étrangère très empathique avec la cause nationaliste québécoise et sa dénonciation du colonialisme économique (anglo-américain et anglo-canadien) et culturel (français), je n’osais m’étonner ouvertement qu’on ne remonte pas au-delà et commençai à m’informer sur l’occupation amérindienne du territoire. C’est ainsi que je pris connaissance des premiers films de la série de treize films de la Chronique des Indiens du Nord-Est du Québec réalisée par le cinéaste Arthur Lamothe, accompagné de l’anthropologue Rémi Savard. Quelle surprise d’apprendre, par exemple, que les 27’000 km² - soit une étendue de la taille du Benelux -, qui venaient d’être concédés par le gouvernement du Québec à une filiale de l’entreprise multinationale International Telegraph Telephone, étaient en fait en territoire amérindien. Et quelle surprise de voir que femmes et hommes innus se battaient au niveau légal, et sur le terrain, pour empêcher ingénieurs et ouvriers d’y pénétrer avec leurs machines et ainsi permettre à leurs chasseurs de continuer à pratiquer leurs activités traditionnelles. Comment, dès lors, accepter l’image dégradée que la population « blanche » québécoise donnait des Premières Nations alors que celles-ci se battaient avec virulence pour défendre leurs droits ? Comment accepter, lorsque je me résolus à aborder ce sujet avec mes collègues, que personne ne veuille en parler ? Comment accepter qu’on puisse être à la fois colonisé et colonisateur ? Surtout quand on vient d’ailleurs et qu’on ne veut pas se comporter en donneuse de leçon[2].

During the same years, another research mandate having to do with the “Man and Biosphere” programme, also a UNESCO programme, and which consisted in studying the history of urbanisation in Quebec, rapidly became a history of the territorial occupation of the Belle Province. A surprise awaited me: for my colleagues, it was clear that this study was to go back to the 18th century, i.e. to the time of the arrival of Jacques Cartier, the first European explorer of the Saint Laurent River. As a foreigner who sympathised greatly with the Quebec nationalist cause and its denunciation of (Anglo-American and Anglo-Canadian) economic and (French) cultural colonialism, I did not dare showing my surprise openly about the fact that such a study would not go back further in time, and I began to inquire about the occupation of the territory by the Amerindians. This is how I discovered the first of a series of thirteen documentary films entitled La Chronique des Indiens du Nord-Est du Québec, directed by filmmaker Arthur Lamothe, who was accompanied by anthropologist Rémi Savard. What a surprise it was for me to learn that, for example, the 27 000 km² – i.e. an area the size of the Benelux – that had been granted by the government of Quebec to a subsidiary of multinational company International Telegraph Telephone, was in fact situated in Amerindian territory. And what a surprise it was, again for me, to see Innu women and men using the law to fight on site, and prevent engineers and workers from entering the area with their machines and, as such, enable their hunters to carry on practising traditional activities. Consequently, how could I accept the negative image the “white” population of Quebec was painting about the First Nations, while the latter were fighting virulently to defend their rights? How could I accept that, when I decided to tackle the subject with my colleagues, no one wanted to talk about it? How could one accept that one is colonised and coloniser? Especially when one comes from elsewhere and one does not want to behave like a sermonizer[2].

Sédentarisation et dépossession

Sedentarisation and Dispossession

Il me fallait comprendre et une manière de commencer à comprendre cette réalité si nouvelle pour moi fut de participer à la production du premier film documentaire de Volkmar Ziegler (1979)[3], avec Joséphine Bacon, traductrice-interprète innue des films d’Arthur Lamothe, aujourd’hui poétesse, « réalisatrice et parolière considérée comme une auteure phare du Québec », pour reprendre les mots de son éditeur « Mémoire d’encrier » (http://bit.ly/JosBacon). Intitulé Tshikainshinut - Notre Parenté, un nom donné par elle, le film met en relation trois situations de marginalisation, volontaire ou non, en Amérique du Nord : celle des habitants portoricains d’un ghetto de New York, celle d’une communauté écologique dans le Vermont et celle du peuple innu, dans les réserves et dans la ville de Montréal. Il s’ouvre sur une question adressée à Joséphine :

I wanted to understand this new reality, and one way to begin to do so was to take part in the production of the first documentary film of Volkmar Ziegler (1979)[3], with Joséphine Bacon, the Innu translator-interpreter of Arthur Lamothe’s films. Today, Joséphine is a poet, “a film director and lyric writer considered as a leading author in Quebec”, in the words of her publishing house Mémoire d’encrier (http://bit.ly/JosBacon). This documentary, which was entitled by her as Tshikainshinut – Notre Parenté, highlights three situations of un-/intentional marginalisation in North America: that of the Puerto Rican residents of a ghetto in New York, that of an ecological community in Vermont, and that of the Innu people in the reserves and in the city of Montreal. The documentary opens with one question addressed to Joséphine:

- Qu'est-ce qu'on fait si on fait un film ensemble ?

– What should we do if we decide to make a movie together?

- Faire un film fictif. Faire un film à partir d'un scénario mais qui va chercher très loin, où tout y est, tu sais, le conflit de soi-même...

– We should make a fictional work; a movie based on a scenario but that goes very far, with everything in it, you know, inner conflict and all that…

Comme par exemple comment c'est pour une Indienne de vivre à Montréal et qu'est-ce que c'est quand elle vit à travers son peuple, quand elle retourne à sa racine, tu sais on est toujours un peu perdus, déracinés. (...).

Like for example what is it like for an Indian woman to live in Montreal and what does it mean when she lives among her people, when she goes back to her roots, you know, one is always a bit lost, rootless. (…)

D'un film, fictif, on pourrait faire un monologue.

We could transform a fictional movie into a monologue.

Aller chercher ce que quelqu'un peut penser de très loin, de très profond (…) dans ses tripes.

We could look for what people really think, deep down (…) in their guts.

Qu'il soit Indien ou non.

Whether that person is or not Indian.

Quelqu'un qui va représenter tous les gens, tout le monde qu'on a toujours empêché d'exprimer sa pensée, par exemple, et ça, c'est pas juste les Indiens, il y a plusieurs peuples comme ça (…).

Someone who represents everybody, all the people who have always been prohibited from expressing their thoughts, for example, and I’m not talking about Indians only, there are many people like that (…).

Dans une autre séquence, alors que nous filmons sur la réserve de Nutashkuan, Joséphine parle du traumatisme de leur sédentarisation au bord du Golfe du St-Laurent, là où les Innus ne vivaient que deux mois en été, les dix autres étant passés en forêt :

In another sequence, while we were filming on the reserve of Nutashkuan, Joséphine speaks about the trauma of their sedentarisation on the shores of the Gulf of St-Laurent where the Innu used to spend only two months of the year in summer, while they used to spend the other ten in the forest:

- Elle a beaucoup voyagé la vieille Marie-Louise, elle a fait des milles et des milles.

– Old Marie-Louise travelled a lot, she did miles upon miles.

Une fois, je lui ai demandé si elle pensait encore au temps quand elle vivait encore à l’intérieur des terres.

Once, I asked her if she was still thinking about the time when she was still living inland.

Elle disait qu’elle ne pensait qu’à ça. (…).

She said that she thought of nothing else. (…).

C’est tout ce qui lui est resté, des souvenirs … quand elle vivait bien, qu’elle dit.

That’s all that remained, memories… of when she had a good life, she says.

- Qu’est-ce qu’elle n’aime pas dans la réserve ?

– What doesn’t she like in the reserve?

- Mais c’est qu’elle ne bouge plus!

– The fact that she no longer moves around!

Et forcément, quand tu ne bouges plus, tu vieillis !

And of course, when you don’t move around, you start getting old!

Dans le temps qu’elle vivait à l’intérieur des terres, elle n’avait pas le temps de penser qu’elle vieillissait. Elle était toujours occupée à poser ses pièges, aller chasser, retourner au campement, aller couper du bois, déménager, changer de campement… Là, tu vis continuellement, tu n’as pas le temps. (…).

When she lived inland, there was no time to think about getting old. She was always busy setting traps, hunting, going back to the camp site, cutting wood, moving the camp, moving to another camp… There, you’re constantly busy; there is no time to think. (…)

Ça doit être différent de fumer la pipe à l’intérieur des terres que sur la réserve… où tout est vide, il n’y a même pas de bois…

It must be something else to smoke a pipe on the land rather than in the reserve… which is empty, there is not even any wood…

…

…

Ça a changé...

It has changed…

Ça nous a détruits un peu d’être sédentaires.

Being sedentary has destroyed us a little.

Cette situation entre deux mondes – autochtone et québécois - dont aucun n’était le mien fut d’autant plus difficile à supporter que je ne voyais pas à ce moment-là quelles compétences j’aurais pu apporter aux Innus pour continuer à être avec eux et leur être utile. J’ai donc décidé de quitter le Québec en 1979. Il était toutefois clair pour moi que mon chemin personnel et intellectuel continuait sur la piste des peuples de la forêt.

This situation between the Indigenous world and that of Quebec, neither of which being mine, was all the more difficult to bear since at the time I could not see what skills I could bring the Innu in order to continue being with them, and be useful to them. I therefore decided to leave Quebec in 1979. Nonetheless, it was clear for me that my personal and intellectual journey would continue to lead me on the path of forest peoples.

De retour à Genève, l’anthropologue Isabelle Schulte-Tenckhoff m’introduisit au Docip, le Centre de documentation, recherche et information des peuples autochtones (voir aussi plus loin). La manière de travailler de cette petite équipe de bénévoles correspondait à ce que les Innus que j’avais connus souhaitaient de la part des non Autochtones. Je me joignis donc à elle au début des années 1980. L’un de ses membres fondateurs, l’ethnologue suisse René Fuerst, connu pour son engagement auprès des Indiens d’Amazonie, m’incita à entreprendre une recherche sur la territorialité des Yanomami du Nord du Brésil. Pourquoi les Yanomami ? Parce qu’une campagne internationale menée depuis le Brésil (à défaut de pouvoir être menée par les Yanomami eux-mêmes, il était pour moi indispensable qu’elle le soit par des nationaux et non par des ONG internationales) militait en faveur de la démarcation de leur territoire, et que j’avais déjà travaillé sur les notions de parcs et réserves au Québec.

Back in Geneva, anthropologist Isabelle Schulte-Tenckhoff introduced me to the Docip, the Indigenous Peoples’ Centre for Documentation, Research and Information (see further on). The way the Docip team of volunteers worked, corresponded to what the Innu of my acquaintance wanted to hear from non-Indigenous people. It was for that reason that I joined the Docip team at the beginning of the 1980s. One of its founding members, Swiss ethnologist René Fuerst, known for his commitment to the Indians of the Amazonia, encouraged me to conduct research on the territoriality of the Yanomami in North Brazil. Why the Yanomami? Because an international campaign conducted from Brazil (if such a campaign could not be conducted by the Yanomami themselves, for me it was indispensable that it was at least to be conducted by nationals and not international NGOs), militated in favour of demarcating their land, and because I had already worked on the notions of parks and reserves in Quebec.

Au Brésil, les militaires étaient alors au pouvoir, et les courageuses protestations contre la construction de la route transamazonienne étaient souvent le fait d’anthropologues et d’avocat·e·s. La qualité de leur travail m’impressionnait. Une bourse de chercheuse avancée du Fonds national suisse de la recherche scientifique arriva au bon moment et me permit de séjourner trois fois chez les Yanomami : huit mois (1981-1982) et sept mois (1986-1987) au Brésil, ainsi que trois mois au Venezuela (1988).

In Brazil, the military were in power at the time, and the courageous demonstrations against the construction of the Trans-Amazonian Highway were often due to anthropologists and lawyers. I was impressed by the quality of their work. An advanced research bursary from the Swiss National Fund for Scientific Research came at the right time, and made it possible for me to spend time with the Yanomami on three occasions: eight months (1981-1982) and seven months (1986-1987) in Brazil, as well as three months (1988) in Venezuela.

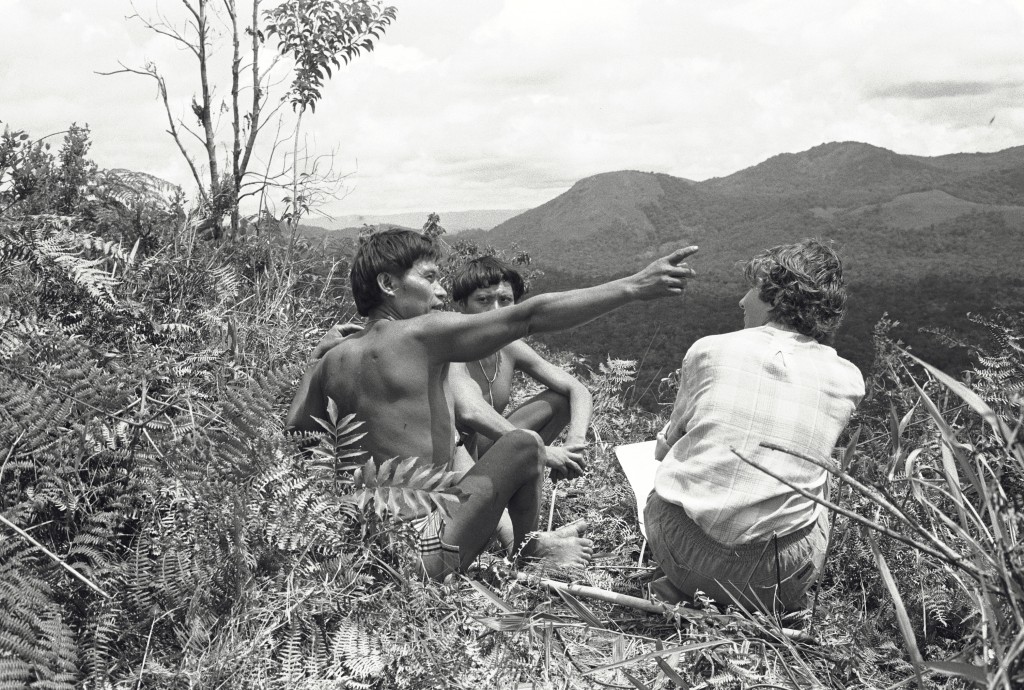

Après le premier séjour au cours duquel je me familiarisai avec la vie yanomami et appris les rudiments de leur langue, j’eus l’occasion de prendre connaissance des interventions des délégations des peuples autochtones à la 2e Conférence internationale organisée par les ONG accréditées à l’ONU et intitulée « Les peuples autochtones et la terre » et qui eut lieu aux Nations Unies, à Genève, en 1981. Je retrouvai dans les interventions des délégués autochtones la même émotion et la même pensée holistique que celle ressentie au Québec en écoutant les paroles de Michel Grégoire. Je pressentis qu’il y avait dans la relation à la terre et au territoire des peuples autochtones quelque chose de plus universel qu’on ne le pensait habituellement. Mon projet de recherche devint ainsi très clair. Je souhaitais montrer au moyen de la cartographie que les Yanomami occupaient réellement leur territoire – aussi vaste soit-il – via leurs parcours migratoires et leurs relations inter-communautaires. Ce ne sont donc pas mes lectures de l’abondante littérature anthropologique sur les Yanomami qui déterminèrent le choix de cette thématique de recherche mais mes travaux précédents sur l’occultation de la territorialité des Innus du Québec, la dénonciation de cette occultation par les délégations des peuples autochtones aux Nations Unies et mon approfondissement des origines historiques de la notion de terra nullius utilisée dans de nombreuses législations nationales (Gonnella Frichner, 2010) et communément traduite sur les cartes et dans le vocabulaire des autorités par le terme de « terras vazias », terres vides.

After my first stay during which I became acquainted with Yanomami life and learned basic knowledge of the language, I had the opportunity to read the papers of delegations of Indigenous peoples at the 2nd International Conference, organised by UN-accredited NGOs, and entitled “Indigenous Peoples and the Land”, and which took place at the United Nations in Geneva, in 1981. In the papers read by the Indigenous delegates, I felt the same emotion and the same holistic thought as that which I felt in Quebec when listening to the words of Michel Grégoire. I felt that there was something more universal than usually thought of, in the relationship between Indigenous peoples and land or territory. My research project then became very clear. Using mapping, I wanted to show that the Yanomami were actually occupying their territory – as vast as it was – via their migration paths and inter-community relations. As such, it was not my extensive reading of anthropological literature on the Yanomami that determined the choice of this research thematic, but my previous work on the fact that Innu territoriality was being eclipsed in Quebec, the denunciation of this situation by the delegations of Indigenous peoples at the United Nations, and my detailed study of the historical origins of the notion of terra nullius, as used in many national legislations (Gonnella Frichner, 2010) and commonly translated on maps and in the terminology used by the authorities as terras vazias or “empty lands”.

Image 2 : Chasseur yanomami sur le plateau de Surucucu (Photo et © Volkmar Ziegler, 1987)

Image 2: Yanomami hunter on the Surucucu Plateau (Photo and © Volkmar Ziegler, 1987)

Je choisis la région de Surucucu au Brésil car les communautés y sont plus proches les unes des autres, ce qui devait faciliter mes déplacements nécessairement nombreux (et à pied) pour réaliser les relevés topographiques permettant de localiser les villages semi-permanents et les chemins qui les réunissaient. A l’époque, les GPS n’étaient pas suffisamment performants pour m’être d’une quelconque utilité. Par ailleurs, la recherche de cartes (très sommaires) et de photos aériennes relevait du parcours du combattant. Seules les images radar utiles à l’exploitation minière étaient facilement accessibles. Chaque document avait en outre une échelle différente - et petite - et aucun ne mentionnait de présence yanomami. Il fallait donc commencer par établir un fond de carte acceptable pour pouvoir ensuite y localiser les toponymes et autres éléments de la territorialité des communautés yanomami de la région.

I chose the region of Surucucu in Brazil because, there, communities lived closer to one another, which was to make my many trips (on foot) easier when conducting topographical surveys, to locate semi-permanent villages and the paths linking them. At the time, GPSs were not performant enough to be in any way useful. Moreover, searching for (very basic) maps and aerial photos was like running an obstacle course. Only radar images useful for mining were easily accessible. Each document had a different – and small – scale and none of them mentioned the presence of the Yanomami. It was first necessary to establish an acceptable base map so as to subsequently locate the place names and other elements of the territoriality of the Yanomami communities in the region.

A ma grande satisfaction, les Yanomami de Surucucu - qui avaient déjà connu une invasion d’orpailleurs en 1975-76, finalement expulsés par la Police fédérale - comprenaient parfaitement mes intentions, même s’ils ignoraient ce qu’était une carte géographique. Il suffisait que je dise que les Blancs prétendaient que leur territoire était vide et que je voulais leur montrer qu’il était plein pour que commence notre collaboration. Sans doute n’aurais-je pas reçu un tel accueil dans une communauté qui n’avait pas encore subi la présence des orpailleurs. A Surucucu, à aucun moment je n’ai eu de problème pour récolter l’information nécessaire pour autant, bien sûr, que je m’adapte à leur propre calendrier d’activités.

To my great satisfaction, the Yanomami of Surucucu – who had already experienced an invasion of gold-miners in 1975-76 who in the end were thrown out by the Federal Police – understood my intentions perfectly, even if they did not know what a geographic map was. To begin our collaboration, all I had to do was to tell them that the Whites claimed that their territory was empty and that I wanted to show them that it was full. I undoubtedly would not have received such a welcome in a community that had not been subjected to the presence of gold-miners. In Surucucu, at no point have I had any problems in gathering the necessary information, as long as I adapted of course to their activity calendar.

Une collaboration idyllique, me direz-vous ? Non, pas toujours. La vie chez les Yanomami est pleine d’émotions parfois éprouvantes, de peurs, de manques mais aussi d’humour. Il faut accepter leurs moqueries, et comprendre qu’on a aussi le droit de se moquer d’eux… Quant à la carte, elle n’a jamais vu le jour. Après sept mois de terrain à Surucucu, notre comportement a été jugé « non adéquat » par les autorités brésiliennes, notre travail interrompu et mes cartes, photos aériennes, notes, etc., confisquées. Il me faudra attendre sept mois pour qu’elles me soient rendues. Je ne sais d’ailleurs toujours pas si, au cas où elles auraient été achevées, j’aurais dû publier ces cartes car elles pouvaient être utilisées contre les Yanomami. Dans de telles circonstances, la responsabilité des chercheur·e·s est énorme et la décision de publier ou non doit être prise avec les communautés autochtones. D’un point de vue purement ethno-géographique, j’avais aussi des doutes sur la notion de « communauté » qui me semblait problématique pour caractériser des entités semi-nomades, sujettes à des fusions et des fissions inter-communautaires, et dont les noms changeaient en fonction des lieux occupés. Les limites entre elles pouvaient être fluides, se négociaient et dépendaient des relations avec les voisins qui pouvaient changer. Le nom d’une rivière variait aussi d’un bout à l’autre de son cours et selon la communauté qui la nommait. La manière de nommer les lieux m’échappait totalement. Un relief pouvait être une « forêt haute » (urihi tire) ou une montagne (maamakë) si le rocher était à nu.

Was this an idyllic collaboration? Not always. Life among the Yanomami is full of sometimes trying emotions, full of fears and shortages, but also humour. One needs to accept their mockery and understand that one is also entitled to mock them… As to the map, it never came into being. After seven months in the field in Surucucu, our behaviour was deemed “inadequate” by the Brazilian authorities, our work was interrupted and my maps, aerial photos, notes etc. were confiscated. I had to wait for another seven months to get everything back. At this stage, I still don’t know whether I should have published these maps, had they been completed, because they could have been used against the Yanomami. Under such circumstances, a researcher’s responsibility is enormous, and the decision to publish or not must be taken together with the Indigenous communities. From a purely ethno-geographic viewpoint, I also had my doubts about the notion of “community” that seemed problematic, when characterising semi-nomadic entities, these being subjected to inter-community mergings and splittings, and their names changing according to where they were settled. The boundaries between them could be flowing, were negotiated and depended on the potentially changing relations with neighbours. The name of a river varied also from one end to the other, depending on the community doing the naming. Naming places escaped me altogether. A relief could be a “high forest” (urihi tire) or a mountain (maamakë) if the rock was bare.

Notre expulsion a coïncidé avec le début de l’invasion du territoire des 10 000 Yanomami du Brésil par 30 à 40 000 orpailleurs (de 1987 à 1991) se soldant par 1 500 à 2 000 morts indiens. Dans ces conditions, comment, d’un point de vue éthique, continuer un travail scientifique, surtout compte tenu de l’engagement pris envers eux ? Comment ne pas participer à la campagne internationale qui aboutit à la démarcation de l’ensemble du territoire yanomami du Brésil, en 1992 ? Quelques articles scientifiques résultèrent de mon travail avec les Yanomami (Birraux, 1992 ; 1995 ; 1997 ; 2005). Un nombre assez considérable d’articles de presse, d’interviews, de conférences-projections des trois films réalisés par Volkmar Ziegler (1984 ; 1986 ; 1994) alimentèrent la campagne dans plusieurs pays européens ; des films dont les bandes-son sont essentiellement consacrées à la parole des Yanomami. Aujourd’hui, il semble évident que les Autochtones s’expriment eux-mêmes sur leur réalité mais à l’époque, cela ne l’était pas. Pas plus que le fait de suivre les Indiens d’Amazonie dans leurs déplacements en forêt alors que les Yanomami y passaient plus de la moitié de leur temps. Ce faisant, nous nous inscrivions en faux contre des équipes de télévision ou de films qui atterrissaient dans les postes gouvernementaux ou missionnaires avec un matériel sophistiqué, restaient une semaine dans le village adjacent, choisissaient les images les plus spectaculaires et n’avaient que faire de ce que disaient et pensaient les Indiens. Cette dernière critique s’adressait aussi aux films ethnographiques de l’époque réalisés chez les Yanomami, même si les séjours de leurs auteurs étaient plus longs.

Our expulsion coincided with the beginning of the invasion of the Brazilian Yanomami territory where 10 000 Yanomami lived by 30 000 to 40 000 gold-miners (from 1987 to 1991), which resulted in the death of between 1 500 and 2 000 Indians. Under these conditions and from an ethics point of view, how could one carry out research work, especially when taking into account one’s commitment to the Yanomami? How could one not take part in the international campaign that led to demarcating the whole of the Brazilian Yanomami territory in 1992? A few scientific articles resulted from my work with the Yanomami (Birraux, 1992; 1995; 1997; 2005). A fairly significant number of articles, interviews, conference-projections of the three films directed by Volkmar Ziegler (1984; 1986; 1994) contributed to the campaign in several European countries; films with soundtracks mainly dedicated to voicing Yanomami opinion. Today, it seems obvious that Indigenous peoples express themselves about their reality, but at the time, it was not so. Neither was the idea of following the Yanomami in the forest where they spent half of their time. By doing so, we were showing our disagreement with the usual flown-in TV or film crews that would land at a governmental or missionary post with their sophisticated equipment, stay in the adjacent village for one week and choose the most spectacular pictures but did not care about what the Indians were thinking and had to say. This last remark also concerns the ethnographic films of the time that were shot among the Yanomami, even if their authors spent more time there.

Voici deux courts extraits de paroles tirées du film La Maison et la Forêt: les Yanomami au temps de la conquête (Ziegler, 1994) prononcées respectivement par Esmeraldo, grand homme de la communauté Tïhïsiporautheri et un jeune de Yutupitheri[5], à propos des orpailleurs :

The following short speeches are extracted from the film La Maison et la Forêt: les Yanomami au temps de la conquête (Ziegler, 1994); they are uttered respectively by Esmeraldo, a headman from the Tïhïsiporautheri community, and by a young man from Yutupitheri[5], concerning the gold-miners:

- Autrefois, quand j’étais naïf, je pensais que les Blancs étaient généreux.

– Before, when I was naive, I thought that the Whites were generous.

Nous allons vivre ensemble, je serai leur ami, je pensais (…).

We are going to live together, I will be their friend, I thought (…).

Aujourd’hui, je serai leur ennemi.

Today, I will be their enemy.

J’étais leur ami, j’étais naïf, je les croyais. Maintenant, je leur serai hostile.

I was their friend, I was naive, I believed them. Now, I will be hostile to them.

Ne venez pas ici ! Vous ne protégez pas ma forêt ! Vous avez déjà une terre où vivre !

Do not come here! You do not protect my forest! You already have a place to live!

Vous volez mon minerai d’étain !

You steal my tin ore!

Quand j’étais naïf, je laissais faire. Maintenant je refuse, je veux protéger ma forêt.

When I was naive, I let it be. Now I refuse, I want to protect my forest.

- J’ai parlé durement aux chercheurs d’or mais ils sont féroces, ils n’écoutent pas.

– I spoke harshly to the gold-miners but they are ferocious, they do not listen.

Ne les envoyez plus chez nous !

Do not send them to us anymore!

Renvoyez-les là-bas d’où ils viennent !

Send them back to where they come from!

Qu’ils rentrent chez eux !

They must go back home!

Quand je vais à Boa Vista, je ne vais pas sur leurs terres, alors, qu’ils ne détruisent pas les miennes !

When I go to Boa Vista, I do not go on their lands; therefore, they must not destroy mine!

Restez chez vous ! Ne venez pas dans ma forêt.

Stay home! Do not come to my forest.

Mais mes paroles se perdent.

But my words are lost.

Image 3 : Deux grands hommes yanomami - Esmeraldo de Hakoma et son homologue de Xitee - me racontent l’arrivée des premiers « Blancs » en 1960, des missionnaires évangéliques nord-américains (Photo et © Volkmar Ziegler, 1987)

Image 3: Two Yanomami headmen – Esmeraldo from Hakoma and his counterpart from Xitee – tell me about the arrival of the first “Whites” in 1960, North American evangelical missionaries (Photo and © Volkmar Ziegler, 1987)

Recherche et engagement : est-ce si différent ?

Research and Commitment: Is it so different?

Au Québec, j’ai découvert le monde des Amérindiens, combien il était occulté, combien leur parole sur le territoire était forte et sensible, et la sédentarisation et la spoliation territoriale traumatisantes. Au Brésil, j’ai vu de près la responsabilité que suppose le travail avec des peuples menacés dans leur existence : nos actions peuvent aggraver leur situation, et la nôtre aussi, mais dans une mesure nettement moindre. Les Yanomami m’ont appris la valeur de la réciprocité : je devais leur donner, tôt ou tard, ce qu’ils me demandaient et j’avais aussi le droit de leur demander quelque chose qu’ils me donneraient tôt ou tard. C’est ainsi que la confiance entre nous s’est créée. Ils m’ont montré le respect de l’autre : pour eux, j’étais faite d’un autre bois mais peu importe, j’étais ce que j’étais. Dans les deux pays, j’ai pu ressentir les effets de la discrimination raciale de la part des autorités et de la population locale. J’ai aussi compris qu’Innus et Yanomami souhaitaient échapper à toute interférence quelle qu’elle soit et décider eux-mêmes de leur destin. Ces expériences sont à la base de la démarche que j’ai essayé de mettre en œuvre dans le cadre du Docip. Ainsi, je ne suis pas certaine que recherche et travail d’ONG soient forcément si différents. L’un et l’autre supposent rigueur, éthique, engagement, responsabilité, et un profond respect de l’altérité.

In Quebec, I discovered the Amerindian world, how much it was being eclipsed, how much Amerindian discourse on territory was strong and alive, and how much sedentarisation and territorial despoilment were traumatising. In Brazil, I saw up close how much responsibility is involved when working with people whose very existence is threatened: our actions can aggravate their situation as well as ours, although to a much lesser extent. The Yanomami taught me the value of reciprocity: sooner or later I would give them what they asked of me, and I was also entitled to ask them something they would give me sooner or later. This is how trust was built between us. They showed me how to respect others: to them, I was made from a different wood, but it didn’t matter, I was what I was. In both countries, I felt the effects of racial discrimination from the authorities and from the local populations. I also came to understand that the Innu and the Yanomami wanted to be free of any interference whatsoever, and wanted to decide their fate on their own. These experiences are at the root of the approach I tried to implement within the framework of the Docip. As such, I am not certain that research and NGO work are so different. Both entail strictness, ethics, commitment, responsibility and a deep respect for otherness.

Le Docip, un centre de documentation, recherche et information au service des peuples autochtones

Docip, a Centre for Documentation, Research and Information at the Service of Indigenous Peoples

Le Docip a été créé en 1978, suite à une demande des délégations des peuples autochtones participant à la première conférence internationale sur leurs droits - la Conférence internationale sur la discrimination à l’encontre des populations autochtones des Amériques - qui a eu lieu aux Nations Unies, à Genève, en 1977[6]. Cette Conférence fut organisée par le Conseil international des traités indiens ou International Indian Treaty Council (IITC) et par les ONG regroupées dans le cadre du Sous-Comité sur le racisme de la Commission des droits de l’homme de l’Organisation des Nations Unies (ONU), et non pas par cette dernière comme il se dit trop souvent. Il fut demandé au Docip de rassembler et diffuser la documentation apportée par les délégations autochtones à l’ONU et de leur servir de secrétariat multilingue. Depuis lors, il leur a fourni des services logistiques, documentaires et d’information tout au long de leur cheminement aux Nations Unies, à Genève et à New York. Au cours des quatre dernières décennies, le Docip a concrètement appuyé les délégations autochtones dans leur mission avant, pendant et après le processus de rédaction et de négociation de la Déclaration des Nations Unies sur les droits des peuples autochtones (ci-après appelée Déclaration), adoptée en 2007 par l’Assemblée générale de l’ONU (ONU/UN, 2007). Pendant les conférences, le Docip ouvre à l’ONU des bureaux équipés de la bureautique nécessaire à la mission des délégations : établissement de systèmes de communication entre elles et leurs organisations restées au pays, traduction de leurs interventions écrites (en quatre, voire cinq langues), service d’interprétariat des discussions informelles entre délégations ou avec les États, y compris les réunions préparatoires (appelées aussi malencontreusement « caucus ») auxquelles toutes participent avant et pendant les conférences, récolte et distribution de leur documentation[7], etc.

The Docip was created in 1978, following a request by the delegations of Indigenous peoples taking part in the first international conference on their rights – the International Conference on Discrimination against the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas – which took place at the United Nations in Geneva in 1977[6]. This conference was organised by the International Indian Treaty Council and by NGOs grouped together within the framework of the Sub-Committee on Racism of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, and not by the latter as is too often believed. A request was put to the Docip to gather and distribute the documentation brought to the UN by the Indigenous delegations, and to serve as their multilingual secretariat. Since then, the Docip has supplied these delegations with logistical, documentary and informational services throughout their way to the United Nations, in Geneva and New York. During the last four decades, the Docip did concretely support Indigenous delegations in their mission before, during and after the drafting and negotiation process of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (referred to as the Declaration hereinafter), adopted in 2007 by the UN General Assembly (ONU/UN, 2007). At the UN, during the conferences, the Docip opens offices equipped with the necessary office automation for the delegations to carry out their mission: communication systems have been established between the delegations and their organisations back home; translation services have been set up for all written speeches (involving four or even five languages); interpretation services have also been set up for all informal discussions between delegations or with the States, including all preparatory meetings (unfortunately also called “caucus”) to which all delegations took part before and during the conferences; as well as documentation collection and distribution[7] services, among others.

Toutes les activités du Docip ont résulté et résultent encore de consultations avec les délégations autochtones ou de demandes de leur part. Nous savons que, particulièrement dans ce domaine, « l’enfer est pavé de bonnes intentions », que nous ne vivons pas la situation de leurs peuples et ne pouvons pas décider de ce qui leur est utile ou non. Les Autochtones luttent pour le droit à l’auto-détermination et en assument aussi les responsabilités, d’autant plus que ce sont d’abord eux qui risquent de souffrir des conséquences des décisions prises. En revanche, nous pouvons diminuer l’énorme fossé en termes de moyens qui les sépare des délégations gouvernementales. Comment, sinon, être en position de négocier si l’on ne dispose pas d’un minimum de moyens mis à disposition sans conditions ? Des relations de réciprocité nous relient : nous leur fournissons des services et ils nous appuient dans nos demandes de fonds. Nous pouvons conseiller les nouveaux-venus sur les procédures de l’ONU et, réciproquement, nous référer aux délégué·e·s les plus expérimenté·e·s si nous nous trouvons dans une situation embarrassante. Ainsi ont-ils aussi un droit de regard sur ce que nous faisons. Nous sommes de leur côté mais ne prenons pas parti dans leurs débats avec les États ou entre eux (principe de neutralité) et travaillons avec tous, quelles que soient leurs positions (principe d’impartialité) ; l’information que nous fournissons est purement factuelle : qui a dit quoi et quand. A eux de faire leurs propres analyses avec leurs communautés, compte tenu de leur situation, du pays dans lequel elles se trouvent, avec leurs propres référents culturels. Et nous ne faisons surtout pas de lobbying à leur place.

All the activities of the Docip have resulted and still result from consultations with the Indigenous delegations or from requests made by them. We know that, particularly in this domain, “hell is paved with good intentions”, that we do not live the situation of their people and we cannot decide what is or not useful to them. Indigenous peoples fight for the right to self-determination and take on all responsibilities in this regard, all the more since they will be the first ones to suffer from the consequences of the decisions taken. On the other hand, we can reduce the wide gap, where means are concerned, that separates them from governmental delegations. Otherwise, how can one be in a position to negotiate, if one does not have the minimum means made available unconditionally? Relations of reciprocity link us: we supply them with services and they support us in our applications for funds. We can offer advice on UN procedures to newcomers and, reciprocally, we can call on the most experienced delegates when we find ourselves in an embarrassing situation. As such, they also have a right to inspection on what we do. We are on their side but do not take a stand in their debates with governments or between them (neutrality principle), and we work with all of them, whatever their position (impartiality principle); the information we supply is purely factual: who said what and when. It is up to them to make their own analyses with their communities, considering their situation, the country in which they are, with their own cultural referents. And especially we do not lobby on their behalf.

Ceci suppose que nous reconnaissions nos interlocuteurs autochtones pour ce qu’ils sont et non pas pour ce que nous voudrions qu’ils soient ou ne soient pas : les idéaliser, ou idéaliser leurs cultures, c’est aussi les nier. Nous sommes conscients des processus de dépossession et de discrimination subis (et souvent encore à l’œuvre), y compris dans le cadre de travaux scientifiques. Nous reconnaissons qu’ils ont leurs propres univers intellectuels et modes de faire et cherchons à éviter toute forme de paternalisme. Tout ceci paraît évident en théorie mais ne l’est pas tant dans la pratique. Nos ornières culturelles sont profondes et il n’est pas toujours facile de s’en extraire, ne serait-ce que momentanément.

This means that we should be recognising our Indigenous interlocutors for what they are, and not for what we would like them to be or not: idealising them or their cultures is also denying them. We are aware of the process of dispossession and discrimination suffered (and often still ongoing), including within the framework of research work. We recognise that they have their own intellectual worlds and ways of doing, and we try to avoid any form of paternalism. While all this seems obvious in theory, it is not so in practice. Our cultural ways run deep and it is not always easy to see beyond, even momentarily.

L’exemplarité du processus autochtone aux Nations Unies

The Exemplary Nature of the Indigenous Process at the United Nations

Se considérant comme des peuples et des nations, les Autochtones se sont efforcés dès la première conférence de 1977 de dépasser le statut d’ONG (attribué par le Conseil économique et social de l’ONU après approbation des États), même s’ils ont dû souvent l’employer pour pouvoir prendre la parole. Le Groupe de travail sur les populations autochtones ou GTPA (1982-2006)[8] fut d’une ouverture inédite : toutes les délégations autochtones, quel que soit leur statut, pouvaient y dénoncer les abus de droits humains perpétrés contre leurs peuples, ceci non pas pour « se plaindre », comme on l’entend dire parfois, mais pour sortir ces derniers des oubliettes de l’Histoire dans lesquelles les États les avaient relégués. Leurs discours, forts, contrastaient avec le monde toujours souriant des diplomates. Face à eux, les gouvernements ont d’abord montré le peu de respect qu’ils leur portaient en envoyant des stagiaires prendre des notes… Puis, grâce à une présidente grecque du GTPA énergique, compétente et empathique, Dre Erica Irene Daes, un projet de Déclaration a pris forme et a été adopté en 1993 par la Sous-Commission de la lutte contre les mesures discriminatoires et de la protection des minorités, une instance composée d’expert·e·s indépendant·e·s. Les États ont alors créé un nouveau Groupe de travail au niveau de la Commission des droits de l’homme, composé de représentant·e·s gouvernementaux. Il en est résulté un nouveau projet de Déclaration, plus proche des positions des États que le précédent, adopté en 2006 par le Conseil des droits de l’homme. Puis une ultime négociation, inhabituelle, a encore été imposée à New York au niveau de l’Assemblée générale, où les Autochtones ne pouvaient pas s’exprimer directement… Autrement dit, ce ne sont pas les obstacles qui ont manqué. Mais à chaque fois, les Autochtones ont insisté et obtenu un statut spécifique (sauf auprès de l’Assemblée générale, ce qu’ils tentent d’obtenir aujourd’hui).

Considering themselves as peoples and nations, Indigenous peoples endeavoured, from the very first conference in 1977, to do away with the NGO status (attributed by the Economic and Social Council of the UN after approval by the States), even if they often have had to use that status to be able to take the floor. The Working Group on Indigenous Populations or WGIP (1982-2006)[8] distinguished itself by its unprecedented openness: all Indigenous delegations, irrespective of their status, could use this working group to denounce human rights abuses committed against their peoples, not with a view to lodging a “complaint”, as has been heard sometimes, but to preventing them from sinking into oblivion where governments had relegated them. Their powerful speeches were in sharp contrast with the forever smiling world of diplomats. Governments first showed how little respect they had for Indigenous delegations by sending trainees to take notes… Then, thanks to the energetic, competent and empathetic Dr Erica Irene Daes, who became Chairperson of the WGIP in 1984, a draft Declaration took shape and was adopted in 1993 by the Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities, an entity made up of independent experts. States then created a new Working Group at the level of the Human Rights Commission, made up of governmental representatives. This led to a new draft Declaration which was adopted in 2006 by the Human Rights Council. This Declaration was closer to the position of the States than the previous one. Then a final and unusual negotiation was imposed in New York, at the General Assembly, during which Indigenous representatives could not speak directly… In other words, the whole process was not short of obstacles. But every time, Indigenous delegations insisted and obtained a specific status (except with the General Assembly, which is what they are attempting to obtain nowadays).

Ceci étant, la Déclaration adoptée en 2007 est probablement le document des Nations Unies élaboré de la manière la plus démocratique qui soit, avec une ample participation des principaux intéressés. En cela, elle se différencie de celle concernant les droits des minorités, où la participation de leurs représentant·e·s a été très faible. Aujourd’hui, le défi principal est sa mise en œuvre. La ratification de la Déclaration implique que les promoteurs de toutes mesures ou de projets concernant des peuples autochtones doivent d’abord obtenir leur consentement, et que celui-ci doit pouvoir être donné librement (sans aucune forme d’intimidation), au préalable (avant que la mesure ou le projet soit réalisé) et en connaissance de cause (après que les peuples concernés aient disposé de l’information leur permettant d’en mesurer les conséquences sur eux et leur environnement). Ce concept est à distinguer de celui de consultation, dont la portée est plus faible.

Despite all this, the 2007 Declaration is probably the UN document that was elaborated in the most democratic way, with ample participation from the main stakeholders. In this regard, there is a clear difference with the Declaration on minority rights, which was written with very limited participation from minority group representatives. Today, the main challenge is its implementation. The Declaration requires that anyone planning to take certain measures or promote a project that will impact on an Indigenous community, first obtains the latter’s consent, which must be given freely (with no form of intimidation), beforehand (before the measure or project is carried out) and with full knowledge of the facts (after the community/-ties concerned have been presented with sufficient information to enable them to figure out the consequences the project will have on them and their environment). This concept must be differentiated from that of consultation, which is not as comprehensive and powerful.

Cette reconnaissance internationale a été possible parce que les Autochtones ont toujours insisté sur leur statut de nation et de peuple. Le mot « nation autochtone » est employé dans l’histoire des Amériques depuis longtemps. Les traités conclus de nations à nations, entre Autochtones et gouvernements, aux États-Unis et au Canada, en sont les témoins, de même, par exemple, que les ouvrages relatant les rapports entre Couronne portugaise et tribus amérindiennes du Brésil. Les termes de « nation » et de « peuple » figurent dans les documents de la Société des Nations traitant des démarches de l’ambassadeur cayuga Deskaheh dans les années 1923-24, représentant de la Confédération des Six Nations Iroquoises. Il est intéressant ici de noter que la lettre de demande d’adhésion de la Confédération à la Société des Nations s’intitule: « The Red Man’s Appeal For Justice ».

International recognition was made possible because Indigenous peoples have always insisted on their status of Nations and Peoples. The term “Indigenous Nation” has been used in the history of the Americas for a long time. The treaties concluded by and between various Indigenous Nations and the governments of the United States and Canada, testify to this, as do for example works recording the reports between the Portuguese Crown and Amerindian tribes in Brazil. The terms “nation” and “peoples” appear in the documents of the League of Nations dealing with the procedures of Ambassador Cayuga Deskaheh, in 1923-24, who represented the Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy. It is interesting here to note that the letter requesting the Confederacy’s membership of the League of Nations is entitled The Red Man’s Appeal For Justice.

Aujourd’hui, on parle d’autochtonie, une expression récente dont je ne suis pas sûre qu’elle soit très heureuse en raison de son caractère abstrait, singulier et quelque peu statique. Les Autochtones ont lutté pendant plusieurs décennies pour se voir reconnaître à nouveau le statut de peuple et les droits collectifs qui s’y rattachent, et dont ils disposaient dans l’histoire. Pourquoi remplacer un terme – peuples autochtones – qui a un sens précis en droit international, pour en introduire un autre ? Certes, et c’est bien là l’un des principaux apports de l’ONU, les Autochtones du monde entier se sont trouvés des parentés claires : la discrimination raciale dont ils souffrent, leur volonté d’autodétermination, la spoliation de leurs territoires et ressources, la spécificité des relations qu’ils entretiennent avec leurs terres, leurs territoires et le monde. Cette parenté les réunit et leur donnent la force de lutter conjointement, en dépit de leurs différences. Mais leur diversité est grande et c’est aussi ce qui fait leur richesse : une diversité qu’il serait regrettable de réduire à un seul mot - l’autochtonie - qui ne la reflète pas directement, pas plus qu’elle n’exprime le dynamisme et la flexibilité de leurs divers modes de pensée. A mon sens, il ferme plus qu’il n’ouvre la porte de l’entendement des façons de penser et d’agir des peuples dont nous parlons. Par ailleurs, pourquoi et comment définir « l’autochtonie » alors que les délégations autochtones à l’ONU n’ont jamais souhaité qu’on définisse le terme « peuples autochtones » ? En effet :

Today, one speaks about indigenousness; a recent expression which I am not certain is totally appropriate due to its abstract, unusual and somewhat static nature. Indigenous peoples have fought for several decades to have their peoples status and the collective rights attached to it recognised again, both of which they used to enjoy in the past. Why replace an expression – Indigenous peoples – which has a specific meaning in international law, to introduce another? Well, and this is one of the main inputs from the UN, Indigenous peoples from around the world are clearly linked on the same grounds: the racial discrimination suffered by them, their will for self-determination, the despoilment of their territories and resources, as well as the specificity of their relationship with the land, their territories and the world. This link brings them together and gives them the strength to fight together, despite their differences. In fact, their wide diversity is a blessing: a diversity that would be unfortunate to reducing to one word only – indigenousness – which does not reflect it directly, no more than it expresses the dynamism and flexibility of their various ways of thinking. In my opinion, it is more likely to close than open the door of understanding of the ways of thinking and doing of the peoples we speak about. Moreover, why define “indigenousness”, and how, when the Indigenous delegations at the UN have themselves clearly stated that they do not wish to see the concept of “Indigenous peoples” being defined? Indeed:

« A plusieurs occasions, les représentants autochtones ont exprimé l’opinion devant le Groupe de travail, que la définition du concept de « peuple autochtone » n’est ni nécessaire, ni désirable. Ils ont mis l’accent sur l’importance de l’auto-identification comme devant être une composante essentielle d’une définition élaborée au sein du système des Nations Unies » (Daes, 1996).

“Indigenous representatives on several occasions have expressed the view, before the Working Group, that a definition of the concept ‘Indigenous peoples’ is not necessary, or desirable. They have stressed the importance of self-identification as an essential component of any definition which might be elaborated by the United Nations system” (Daes, 1996).

Les délégations autochtones ont avancé plusieurs arguments à cet égard. Le plus important est qu’une définition pourrait exclure des peuples se considérant comme autochtones mais ne répondant pas à des critères élaborés à l’ONU (c’est-à-dire en accord avec les États). Ceci se comprend aisément si l’on aborde la question dans une perspective historique. En effet, nombreux sont les peuples autochtones qui ont dû et doivent encore cacher leur identité sous peine de discrimination, voire de persécution. D’autres peuples ont été définis comme autochtones par les États dans le but de restreindre leurs droits, au nom d’une idéologie raciste, qui mettait (ou met encore) en avant la part de « sang indien » de chacun·e pour le·a catégoriser « autochtone ». Par ailleurs, les délégations insistent sur le fait que le mot « peuple » n’est pas défini en droit international. Dès lors, pourquoi vouloir absolument définir l’expression « peuple autochtone » ?

The Indigenous delegations have given several arguments in this regard. The most important one being that a definition could exclude peoples who consider themselves as Indigenous, but who do not meet the criteria elaborated by the UN (i.e. in agreement with the States). This is easily understood when one tackles the issue from a historical perspective. Indeed, there are many Indigenous peoples who have had and still have to hide their identity, to avoid discrimination or even persecution. Other peoples have been defined as Indigenous by the States with the intention of restricting their rights, in the name of a racist ideology that brought (or still brings) to the fore their “Indian bloodline” so as to categorise them as “Indigenous”. Furthermore, delegations insist on the fact that the word “peoples” is not defined in international law. Consequently, why should it be absolutely necessary to define the expression “Indigenous peoples”?

Cette discussion est intéressante car elle met le doigt sur le fait qu’une définition exclut toujours tout ce qui n’y entre pas. Par ailleurs, le refus des délégations autochtones d’adopter une définition une fois pour toute ne relève pas, à mon sens, d’une simple posture politique, mais est tout autant à placer dans le contexte d’une pensée flexible qui refuse l’établissement de limites rigides parce qu’elle se veut intégratrice, comme le montre la première citation de Joséphine Bacon, au début de ce texte.

This discussion is interesting because it shows that a definition always excludes that which does not fit into it. Moreover, the fact that Indigenous delegations refuse to adopt a definition once and for all, does not – in my opinion – have to do with a simple political position, but also needs to be placed in the context of a flexible thinking refusing the establishment of rigid boundaries because it is an integrating thinking, as shown by the first quotation of Joséphine Bacon, at the beginning of this article.

Conclusion : travailler avec les peuples autochtones

Conclusion: Working with Indigenous peoples

Mon parcours avec les peuples autochtones a été marqué par divers questionnements, dont celui du rapport sujet-objet, tel que prôné par le positivisme qui dominait la pensée en sciences sociales dans les années 1970. Cette question est-elle vraiment résolue ? En théorie, probablement, mais en pratique ? Bien sûr, on parle aujourd’hui de « partenaires autochtones », tant dans le monde de la recherche que dans celui des ONG pour évoquer une relation plus collaborative et égalitaire que par le passé. Tant mieux, mais encore ? Qui sont ces partenaires ? En connaît-on l’histoire telle qu’ils l’ont vécue ou seulement l’histoire officielle ? Qui finance le travail conjoint ? Comment les accords entre partenaires sont-ils conclus ? Les partenaires peuvent-ils vraiment s’exprimer sur un pied d’égalité ? Admettons que ce soit le cas. Il reste que face au mode dominant de pensée, le chemin est encore long jusqu’à ce que les peuples autochtones soient vraiment entendus et compris. Il est selon moi primordial de multiplier l’enregistrement de leur Histoire et de leurs histoires, de leurs visions du monde, de leurs positionnements face à la situation qui est la leur. La manière de le dire, de le transmettre, est aussi importante que le contenu en tant que tel. C’est pour cela qu’il faut éviter de réduire leur discours à nos concepts et à nos analyses. Ainsi notre mode de pensée s’en trouvera aussi enrichi.

My professional journey with Indigenous peoples has been characterised by various questionings, including that of the subject-object relationship, as advocated by Positivism which prevailed in the Social Sciences in the 1970s. Is this question truly resolved? In theory probably yes, but what about in practice? Of course, today one speaks of “Indigenous partners”, as much in the scientific world as that of NGOs, to evoke a more collaborative and egalitarian relationship than in the past. All the better, but still, who are these partners? Do we know their history as experienced by them or only the official history? Who is financing the joint work? How are agreements between partners entered into? Are the partners really able to express themselves on an equal footing? Let’s say this is the case. The fact remains that, faced with the dominant way of thinking, there is still a long way to go before Indigenous peoples are truly heard and understood. In my opinion, it is essential to multiply the recording of their History and their stories, their visions of the world, their own way of positioning themselves in the face of their own situations. The way to say it, to transmit it, is as important as the content as such. That is why one must avoid reducing their discourses to our Western concepts and analyses. In this way, our own way of thinking will be enriched.

Image 4 : Participant·e·s au 1er Symposium d’histoire orale sur les peuples autochtones aux Nations Unies intitulé « Peuples autochtones aux Nations Unies : de l’expérience des ancien·ne·s·à la capacité d’agir des jeunes générations » (P. Birraux est au premier rang, à gauche) (Photo et © Stephane Pecorini, 2013)

Image 4: Participants at the 1st Symposium of Oral History on the Indigenous Peoples at the United Nations entitled “Indigenous Peoples at the United Nations: From the Experience of the First Delegates to the Empowerment of the Younger Generations” (P. Birraux is in the first row, on the far left; photo and © Stephane Pecorini, 2013)